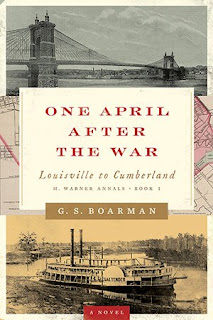

G.S. Boarman is the author of the new historical novel One April After the War: Louisville to Cumberland, the first in a series.

Q: What inspired you to write One April After the War?

A: There were three specific incidents, years apart that suddenly came together and sparked the story line, but there was also the knowledge and experience of people like Mary Warner that I had observed up close and I wanted to explore those people from the inside.

The three specific events are as follows:

— I came across a trend in a family ancestry book of naming almost every daughter, even sisters, Mary and then addressing all these Marys by their middle name.

One such “Mary” especially caught my attention. She was a cousin of my paternal grandmother and her full name was Mary Eulalia, but off to the side in quotes was “Lally.”

I thought that was the sweetest nickname I had ever heard and I determined that if I ever wrote a book, Lally would be my main character.

— My older daughter endured a series of emotional and behavioral challenges, from Day One: extreme separation anxiety, the inability to sleep through the night (she was nearly 11 before that happened), chronic depression (that required experimenting with several fairly heavy drugs), and, finally, a diagnosis of ADD at age 17 (much later than most children are diagnosed).

By this time, she had just had enough of doctors and drugs and counselors and seeming failures, and she just exploded one day and asked why all this happened to her. It was the ADD diagnosis that was the final straw.

I began to research ADD and when it first showed on the medical radar and found the first mention of such a disorder or syndrome in the very late 1700s (though it was called something else entirely at that time).

— My younger daughter once asked me, after watching a show in which it was mentioned, what the Secret Service did.

I immediately answered that the Service protected the president, but then I began to research that as well and came to learn that their first, and continuing mission, is to guard against counterfeiting the nation’s currency (first and foremost among other crimes against the federal government).

It was as I was researching the Secret Service and reading an incredibly interesting book on early counterfeiting (David R. Johnson’s Illegal Tender: Counterfeiting and the Secret Service in Nineteenth-Century America) that I began to formulate the story.

I worked on One April (and its sequels at the same time) for several years in between the usual demands of life, most of it spent in research.

Q: You’ve said of your character Mary Warner that she “did not set out to break gender rules; she simply did not want to live under someone else’s arbitrary (as she saw them) rules.” Can you say more about the role gender plays in the book, and about how you created Mary Warner?

A: The era in which the book(s) is set was ruled by two calcified social concepts: women were inferior to men and blacks were inferior to whites. Mary Warner would have grown up with these two tenets always before her.

As a female she would have known the limits she faced, but whereas most women at the time (but not all; there had already been in motion the women’s suffrage movement) would have accepted this as the law of both nature and God, Mary Warner would see these limits as imposed upon her and not innate to her gender.

She grew up with six older brothers and one younger brother, so she was very aware of what boys did and could do and often challenged herself to keep up with them.

As the seventh child in a family of 13 children, she was the exact middle child and, moreover, she straddled the gender line (the one younger brother gave her the once circumstance she had where she could rule over a brother, if only when young).

The Warners lived on a farm, distant from the city of Louisville, so that gender lines were sometimes blurred — the work of the farm didn’t respect gender differences: the work simply had to be done.

This is amplified during the war when most of her brothers were gone and she and her younger sisters and younger brother had to pick up the slack.

As what happened during WWII when Rosie the Riveter realized she could do the work of men and enjoyed earning her own money, Mary Warner did not see the need to limit herself to working only in the home and hearth.

It is important to know that Mary Warner came of age during the war — her formative years occurred during a time when gender norms were stretched while the men were away. Seeing herself in this “stretched” gender role would have seemed normal to her.

So that what others saw as Mary stepping outside of her “sphere,” Mary saw as merely continuing as she had done growing up — doing the work required, taking care of herself as she saw fit, pursuing her interests.

In sum, she acted the part of a bachelor, more so, since she was literally a single person, being left alone after the deaths of her family, spread over the years of the war and the early years of Reconstruction.

Mary Eulalia “Lally” Warner is an amalgamation of myself and my two daughters.

Generally speaking, the negative traits Mary displays come from me. She has a short fuse and is too quick to speak her mind, often insulting other people and often not realizing she has done so.

But her other traits come from my daughters. The quick intellect belongs to both of them, but the ability to play the piano by ear and to draw with absolute fidelity to the subject (both revealed in later books) belong to my older daughter.

The daredevil attitude to try anything belongs to my younger daughter, who likes to hike through any terrain, goes spelunking, mountain climbing, and shooting rapids (sometimes, she terrifies me).

Despite Mary Warner’s eccentricities, it is my hope that she can be seen as “every woman,” looking for her own level in the world, no matter the circumstances.

It was the curious habit of naming so many daughters Mary in my own family that suggested this to me: they are all Mary, but they are also all different, they all answer to different middle names.

And in the book I had her become known simply as M to hopefully underscore this universality, of distilling her down to her most basic element, neither man nor woman but simply a possibility — “m” is the sound made when a decision is being mulled over, the sound of maybe.

M is also the middle letter of the alphabet, as M is the middle child.

Q: Can you say more about how you researched the book, and did you learn anything that especially surprised you?

A: I did a lot of research, probably more than I needed to; I went down a lot of rabbit holes and came out empty, but I did not want to leave any stone unturned.

I tremendously enjoyed doing the research and finding little tidbits and asides that I could add to my story, little layers and textures that I think make the story seem as if it really happened.

I downloaded old maps of every town the train stops in and read as much history about each town as I could find. I read books on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad — I felt as if I knew every mile of that road at one time.

I read books on train engines of the 1860s and 1870s and books on passenger cars and freight cars. I read books on counterfeiting and the Secret Service (though there is precious little available to the general public).

One of the single most important sources I used and still subscribe to is newspapers.com, which gave so much information about the years of my books, but more importantly the information is as the people at that time knew it, so it is devoid of the perspective from the 21st century.

As I did my research, I came across several items that sent a little thrill through me, and anyone who has ever written something and agonized over whether it is good enough to be published will tell you, I looked for anything I could take as a sign that I was on the right track, that I was meant to write this story.

The first town I researched was Martinsburg, West Virginia (which is covered in Book 3, The Will of the Turntable).

In Martinsburg, I found living in 1870 Commodore Boarman, a distant relative on my father’s side. In Martinsburg, I also found Eulalia Street (Eulalia being Mary Warner’s middle name and source of her family pet name of Lally). Both of these discoveries were sources of encouragement to me.

There were also news items I came across that fit so perfectly into the story that writing the story seemed a natural extension of those news items.

The weather, for instance, was followed faithfully from “meteorological reports” found in the newspapers. At first this was an obstacle, but then it became a force in the story.

Originally the story was to have started on a glorious day in March, but the weather was wretchedly chilly and rainy for weeks, so I had to adjust my story, but then the weather became important.

A steamboat, Legal Tender, was held up in Cincinnati for days because of the flooding of the Ohio. I could not pass up something as perfect as Legal Tender as a mode of transportation for two Secret Service agents, charged with protecting the nation’s legal tender.

Legal Tender was unable to pull away from Cincinnati until the very early hours of April 1, so that became the beginning of my story and ultimately determined that the books (both One April After the War: Louisville to Cumberland and One April After the War: Cumberland to Washington) would cover the month of April, one chapter for each day of the month.

That Easter of that year (and, coincidentally, of 2022 as well) occurred in the middle of the month made it the perfect place to split the story, so that Book 1 covers April 1-16 and Book 2 covers April 17-30 (plus a few days in May).

And, again, the actual weather of Easter 1870 fell perfectly in my lap as a kind of literary device: as the weather deteriorates from unusually warm to wintry (cold with sleet and snow), the events of the story also descend into violence and the beginning of the ultimate crisis for Mary Warner.

Q: Can you say more about what you hope readers take away from the story?

A: As I mentioned earlier, I would like for readers — anyone, but especially women — to see in Mary Warner a little of themselves, both the unpleasant and the interesting, and know that possibility springs from both types of traits, that even the worst moments in life are important and even necessary.

I would also like for people to see in Mary Warner perhaps someone that they see as odd and awkward and to understand that probably no one knows that better than themselves, that nevertheless these people are valuable and worthy of patience and due consideration.

It is difficult to be the different one and it is not always a choice, that conforming isn’t a matter of trying harder or smiling more or mimicking the prevailing version of womanhood or manhood. Sometimes that just isn’t possible.

I, of course, also hope readers simply enjoy the ride.

Q: This is the first in a series--can you discuss what's coming next, and what you're working on now?

A: The first three books are currently available (on Amazon). I released them together because they are an opening trilogy to the series. The series covers the decade 1870-1880, and it was my intention to write one book for each year.

The year 1870, however, had so much to cover — introducing the characters, the culture of the time, a parallel storyline, the politics, all of which can now be carried forward into the next years — that three books were needed.

Book 2, One April After the War: Cumberland to Washington, finishes the events of April, at the end of which Mary Warner and the two Secret Service operatives (Merritt and Argent) separate.

Book 3, The Will of the Turntable: The Way Home, reunites the characters after Mary Warner has had something of a rebirth before returning home to Louisville.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: April 1870 and April 2022 are exactly the same: both begin on a Friday and Easter of both years is the 17th and the full moon is one day different (April 15 in 1870 and April 16 in 2022).

Consequently, June 1870 (most of the time spent in Book 3) is also the same: both begin on a Wednesday, the Feast of Corpus Christi is on the 16th, and the full moon is one day different (June 13 in 1870, June 14 in 2022).

It might be fun for readers to follow the characters in “real” time this year, reading a chapter a day (for the first two books). I have appended a calendar designed especially to allow readers to follow along this April.

If readers or prospective readers have any questions or comments, please contact me through the website gsboarman.com.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment