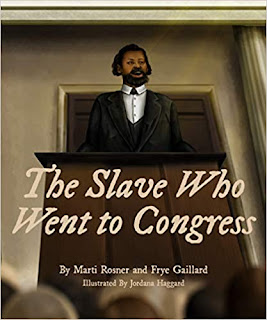

Frye Gaillard is the author, with Marti Rosner, of the new children's picture book biography The Slave Who Went to Congress. His many other books include A Hard Rain: America in the 1960s, Our Decade of Hope, Possibility, and Innocence Lost. He is the writer-in-residence at the University of South Alabama, and he lives in Mobile, Alabama.

Q: Why did you and Marti Rosner decide to write a book about

Congressman Benjamin Sterling Turner (1825-1894), and why did you write the book in his

voice?

A: Marti and I discovered the story of Benjamin Sterling

Turner when I was researching another book, Cradle of Freedom, about the civil

rights movement in Alabama. I was in Selma, Turner's hometown, and stumbled

upon his story.

Marti, who has been a good friend since around 1980, was

about to retire from a career in elementary education and wanted to write a

children's book. She introduced me to the subtlety and sophistication of

children's picture books, and we decided to write Turner's story.

In our research, we discovered the speeches he had made as a

member of Congress, as well as other writings, which gave us a sense of his

sensibilities and his voice. We decided that letting him tell his story gave a

greater feeling of immediacy for young readers. We had read other books such as

My Name is James Madison Hemings, which employed a similar device.

Q: How did you research the book, and did you learn anything

that especially surprised you?

A: We researched the book at the Selma Public Library,

which had extensive files on Turner including a brief, but contemporaneous

biography written by a member of his family. We also benefited from the work of

Selma historian Alston Fitts, who had done extensive research on Turner and

made his files available.

Two museums in Selma, the National Voting Rights Museum and

the Old Depot Museum, also had preserved old photographs and flyers advertising

Turner's livery stable business, etc. - which became valued primary sources.

In addition, it so happened that during the Civil War, when

his owner went off to fight for the Confederacy, he left Turner, his literate

slave, in charge of the St. James Hotel, Selma's largest. That hotel was still

in operation when we were researching the book, and is now being renovated to

preserve its beautiful historic character. We stayed there, which gave us an

added feeling for the history.

And we visited the monument at Turner's gravesite,

erected by an interracial group of Selma citizens roughly a century after his

death.

I suppose the thing that surprised us most was the character

of Benjamin Sterling Turner. He was so determined, so resolute, in his pursuit

of literacy, freedom, and equal rights, and yet he possessed a generosity of

spirit that is rare.

He favored the right to vote for former slaves, reparations

in the form of land on which they could build their lives, mixed race schools

in which all children could get an education, but he also opposed punishment

for former Confederates and set out to "bind up the wounds of war."

We thought of Abraham Lincoln's Second Inaugural, "with

malice toward none," and the 20th century examples of Nelson Mandela and

Martin Luther King, and thought this largely forgotten figure from the

difficult years of Reconstruction should be celebrated for his heroic and

farsighted vision.

Q: Your book A Hard Rain addresses the 1960s--why did you

focus on that particular decade, and do you see echoes from the '60s in today's

politics and culture?

A: I came of age in the 1960s. I was in junior high school

when the decade started, and was graduating from college and beginning a career

as a journalist when it ended.

During those years, growing up in the South, I was

captivated by the drama of the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War and the

protests against it, the women's movement, the environmental movement, etc.

I was fascinated not only by the politics of social change,

but cultural happenings as well - the music and literature of the decade, the

space race, dramatic moments in the world of sports like the rise of Muhammad

Ali and the Olympic protests of 1968. It was a dramatic time.

And yes, I do see parallels for today. The great story arcs

of idealism and hope on the one hand, and division and cynicism on the other,

continue to shape the life of our country.

Q: You write, "I hope to offer a sense of how it

felt" to experience the '60s. What impact did the decade have on you

personally?

A: I was forever changed by the decade. I saw people about

my age, and some who were older, act on a leap of faith that our great country

could be made even greater - more inclusive - that our founding ideals could be

made more real. I have never gotten over that leap of faith, and all of the

hope that went along with it.

That hope has been tested in recent years, but I cling to

the notion that it will be vindicated in 2020. We are living, again, in a

watershed time.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: After writing A Hard Rain, which was a massive

undertaking, and then a children's book, which was a new experience, I am not

writing anything right now.

I'm enjoying my work as Writer in Residence at the

University of South Alabama. My duties include not only working with students

at the university, but doing public programs about the issues raised in these

books.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: I have a website, fryegaillard.com, that you can glance at if you'd like. I

do appreciate your interest.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment