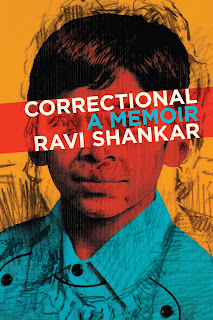

Ravi Shankar is the author of the new memoir Correctional. It focuses on his experiences with the criminal justice system. His many other books include The Many Uses of Mint. A poet, translator, and professor, he founded the arts journal Drunken Boat. He teaches at Tufts University and the Cambridge Center for Adult Education.

Q: Why did you decide to write this memoir, and how was the book's title chosen?

A: As a writer, I don’t think I had a choice in the matter; as soon as I realized that I was going to have serve 90 days as a pretrial detention, I adopted the mindset of an immersion journalist, knowing that it would help ensure my survival to feel that the most difficult and humiliating period of my life could yet be used for something positive and redemptive.

Most of my other books are poetry, and I love language’s capacity for homonymy and polysemy, or the capacity for a word to have multiple meanings; “Correctional” both refers to the Hartford Correctional Center (HCC) where I served my time, but also to my reclaiming of a story that was told sensationally and inaccurately by the local media and a chance to introspect as well as a chance to redress my own wrongs.

Therefore, I have six letters interspersed throughout the book as an architectural spine to the story; each of these letters, named for the six seasons in India, is addressed to someone in my life with whom I hope to “correct” things.

Finally, there’s a more holistic resonance that I intend with the title, which is bringing to readers an awareness of the broken parts of our legal and criminal justice system (many parts of which are still rooted in Puritan and Calvinist ideologies around shaming and the predestination of the elect) and how much it is costing us all socially, economically, emotionally, and spiritually as Americans.

Q: You write, “In Australia, I regained my voice and began, hesitantly at first, then more confidently, to be able to talk and write about everything I had been through. This is how, in the end, the worst years of my life became my greatest blessing.” What impact did writing the book have on you?

A: I have come out of the experience of writing this book utterly transformed, for I cannot unsee what I have seen and brushing up against the humanity of men whom I never would have otherwise met has triggered an awareness in me that’s motivated me to become an advocate for criminal justice reform.

I mention the Japanese craft of kintsugi in the book, which is the art of repairing broken ceramics with glue and gold dust, strengthening it while calling attention to its imperfections. As I write in Correctional, “I am rebuilding my life, making it stronger, at the very places where it had been broken.”

Part of that is using my firsthand knowledge of a carceral facility to supplement the overwhelming statistics to urge us towards meaningful change. Going through that hardship, which was so brief compared to so many others, made me dig into the history of the mass incarceration, how and when it became racialized, and I received a Ph.D. from the University of Sydney doing research into the subject.

I believe my story is unique because I’m both someone who has benefited from immense privilege and someone who has been vilified and discriminated against by those same systems.

Writing this book has made me realize that I’m much more connected to all people, regardless of socioeconomic background or race or gender or vernacular, than I might ever have imagined, and that by telling my story, I might encourage others to tell their own.

Q: In an essay for The Marshall Project, you write that “nothing made me feel more American than being incarcerated.” Why was that?

A: I was born in Washington, D.C., and mainly grew up in Northern Virginia, so despite my parents’ ancestry from South India, I’m a blue passport-carrying, apple-pie loving citizen, as American as Thomas Jefferson, but somehow, it never quite felt that way.

Part of that might be due to the difficulty I had assimilating due to my difference to the kids around me; part of it arises from my parents’ attempts to preserve their Hindu ideals; yet another part of it comes from the seismic shift towards the way brown bodies were treated after 9/11, even subconsciously by otherwise kindly people.

However, amazingly, I found when I was at HCC, there was this democratic leveling where everyone was assigned a number and looked at the same in the eyes of the institution.

The United States of America was birthed from an original hypocrisy, and the rhetoric of free will and the reality of subjugation were both present at the ratification of the Constitution.

For most of my life, I had experienced the former, probably even taken for granted many of the basic freedoms I possessed, but it was not until I spent 90 days at HCC that I really experienced the latter; having had that full spectrum experience gives me a much clearer sense of what it really means to be American.

Q: In the book, you write, “The most important takeaway of my experience is the conviction that the raw, unvarnished truth of the American carceral system can no longer be a dirty secret.” Can you say more about that, and about what you hope people take away from the book?

A: According to the American Action Forum (AAF), a center-right organization, the United States spends nearly $300 billion annually to police communities and incarcerate 2.2 million people.

Adding the societal costs, such as lost earnings, long term health effects, and the irreparable damage to families of incarcerated people, AAF estimates the total measured cost of our marginally effective criminal justice system to be $1.2 trillion.

A Department of Education report from 2016 further notes that since 1990, state and local spending on prisons and jails had risen at a rate three times faster than spending on schools. Overlay that with the statistics about the racial makeup of the prison population and it’s a downright stark, uncharitable, even malevolent reflection of who we are in this moment.

Do we really want to be home to 5 percent of the world's population but nearly 25 percent of the world's imprisoned people? As the research from the AAF indicates, it’s not a Republican or Democratic issue, it’s a human one and it’s costing us dearly.

I hope Correctional’s readers will see these men as I encountered them: complex, emotional, injured individuals who had been let down by various institutions over the course of their lives.

That’s not to make an excuse for their poor decisions, but rather to allow us to see that they are us, if not for the luck of the genetic lottery, and we are them, all of us citizens of this country, all endowed by our Creator with certain unalienable rights, among them Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

While I hope that my memoir is lauded for its craft and linguistic prowess, I want this book to be more than a static literary artifact but an invitation to open our eyes and heart, to write to our legislators, and to fight as hard as we to correct those original sins and forge a more diverse and equitable society.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I’m currently teaching creative writing at Tufts University and finishing work on a new book of poems that brings some Asian forms, such as the Cambodian pathya vat and the Sanskrit pankti, into English.

I also have an advance contract with an academic publisher to finish working on a book about prison memoirs by American men of color, beginning with Austin Reed (whose mid-19th century book was just recently discovered and published) and including Malcolm X, Mumia Abu Jamal, Lil’ Wayne, Reginald Dwayne Betts.

These books offer a fascinating window into a place that was built not just to keep people in, but to keep the public out.

I’m a big believer in bibliotherapy and using writing to help heal and grow, and so I’m volunteering to teach in prisons and as a writer—and amazingly, an actor!— for And Still We Rise, a Boston-based theater company comprised of people affected by the criminal justice system.

Finally, when you go through a turbulent personal time, you find out quickly who your true friends are; some disappear and still others hope to take advantage of you, swooping in like vultures to the carrion of your intellectual property.

I founded, edited, and ran Drunken Boat, one of the world’s first electronic journals of the arts, for over 15 years, but when I was having my trouble and entrusted someone to run the journal, she tried to put it in her name, siphoned funds, and ultimately slandered me to the staff and vandalized the site.

So, I’m in the process of having discussions now with numerous individuals and organizations about resuscitating this magazine, which truly has been a unique space for literature and works of art endemic to the medium of the web.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: Just as during the civil rights movements, there were freedom riders who risked their lives to help end segregation, there are numerous individuals and organizations who are dedicated to criminal justice reform, from the Marshall Project and the Southern Law Poverty Center to local organizations, like Garden Time, which brings horticultural skills to inmates in Rhode Island.

I encourage you to get involved and to report back what you see. If you can’t tell, I’m passionate about this conversation! And I would be glad to visit any book club or salon to discuss the creation of Correctional.

In addition to teaching at Tufts, I teach at the Cambridge Center for Adult Education and am helping organize an immersive writing retreat in Athens, Greece, for the New York Writers Workshop.

If you are interested in poetry, you can check out The Many Uses of Mint, my New and Selected poems, as well as Language for a New Century, a Norton anthology I helped co-edit that contains 450 poets from 61 different countries writing in over 40 different languages.

Follow me on the socials @empurpler and @correctionalmemoir and remember that we are all indelibly ineradicably interconnected.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment