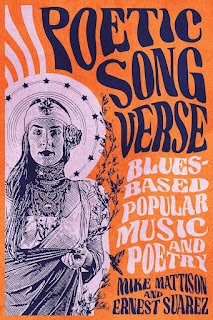

Mike Mattison and Ernest Suarez are the authors of the new book Poetic Song Verse: Blues-Based Popular Music and Poetry. Mattison is a singer, songwriter, and founding member of Scrapomatic and the Tedeschi Trucks Band. Suarez is the David M. O'Connell Professor of English at the Catholic Universitiy of America in Washington, D.C.

Q: What inspired you to write Poetic Song Verse, and how

would you define the concept of “poetic song verse”?

A: Our love of songs with poignant lyrics inspired us to write the book. Bob

Dylan’s 2016 Nobel Prize in literature affirmed what we already knew—that song

verse can be a form of literature.

For many years there’s been a debate about whether or not song lyrics can be poetry. Our assumption is that song lyrics can be poetic and poetry can be musical, but that songs and poems are different things, and one form doesn’t need to be justified by the other.

|

| Ernest Suarez |

We engage in an extended discussion of the roots of the

relationship between blues-based music and poetry. By examining the confluence

of blues and poetry, and by considering the creative practices of various

seminal artists and the cultural conditions and landscapes in which they

worked, we identify a relatively specific subgenre of song that’s also a form

of literature.

We use “poetic” to describe lyrics that have literary intent and that

consciously strive for aesthetic impact.

We don’t mean “literary” in the clichéd sense of high-minded, or heaven forbid, willfully opaque, but to denote linguistically rich compositions that operate on many levels simultaneously, incorporating image, metaphor, narrative, linguistic nuance, and play in ways that often deliberately correlate to broader cultural conversations.

Lyrics that seek to transcend the grasp-and-release mechanism of pure entertainment. Lyrics that prick our curiosity and invite repeated visits and renewed scrutiny (which, in itself, is a fine step toward a definition of “literary”).

Are some lyrics more consummately literary than others? Yes, of course. And the author’s intent is one of the main drivers of their success.

What we call poetic song verse isn’t poetry set to music, like the Beats’ poetry with jazz accompaniment, but it sometimes takes a hybrid form in recordings like Gil Scott-Heron’s or Leonard Cohen’s.

The distinction we draw, while acknowledging room for ambiguity and debate, rests on the symbiotic relationship that most often occurs when potent lyrics and sonics are developed together.

By “sonics” we mean every aural dimension of song, including voice, instrumentation, arrangement, and production. Simply put, how a song is sung, performed instrumentally, arranged, and recorded affects how the lyrics are experienced emotionally and intellectually. Hence, different arrangements, productions, and performances of the same lyrics are experienced differently.

In poetic song verse sonics combine with verbal techniques often associated with poetry—imagery, line breaks, wordplay, point of view, character, story, tone, and other qualities—to create a semantically and emotionally textured dynamic, resulting in songs that, in T. R. Hummer’s formulation, “tap into the fundamental power of the subterranean unity of music and language, of tone and word.”

Q: What impact did the artists of the late 1950s and 1960s

have on musical tastes and traditions?

A: In the late ‘50s and the ‘60s Beat coffee houses, bookstores, and nightclubs

sprang up across the United States and spread to Western Europe.

Bob Dylan, Mick Jagger, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Jimi Hendrix, Van Morrison, Jim Morrison, Joni Mitchell, David Crosby, Neil Young, Stephen Stills, and others embraced the blues and Beat coffeehouse culture, where they encountered contemporary poetry, rural blues, and folk music.

After putting rock ’n’ roll of their youth aside for a handful of years, many ‘60s songwriters returned to the rebellious rhythms of ‘50s rock ’n’ roll and wedded it with verse inspired by contemporary poetry.

In the mid-‘60s Dylan’s rock ’n’ roll–Beat poet persona strengthened his already active sense of the possibilities between poetry and music and led to Bringing It All Back Home (1965), Highway 61 Revisited (1965), and Blonde on Blonde (1966), albums that ignited an explosion of poetic song verse.

Instead of portraying themselves as the descendants of Woody Guthrie, Bukka White, and Pete Seeger, artists returned to the theatrics of Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and Jerry Lee Lewis but retained the cerebral, self-consciously artistic emphasis that characterized songs and poetry in Beat coffeehouses.

This combination released Dylan and others from songwriting conventions that ranged from the length of individual songs to how albums were conceptualized, recorded, and produced.

In essence, the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, the Doors, the Who, Jimi Hendrix, the Kinks, and others followed Dylan’s lead and expanded ‘50s rock ’n’ rollers’ sounds and emphasis on performance, assuming often extravagant yet artistically resonant personae that resulted in songs and albums replete with ambitious wordplay and sonic arrangements.

Q: How did you research the book, and did you learn anything

that especially surprised you?

A: We’ve both been listening to most of the music we address for most of our

lives. We read everything we could find related to our topic, but we didn’t

want the book to be conventionally academic. We wanted it to be sophisticated,

but readable and lively.

In our book, we draw on biographies, histories, popular magazines, personal reminiscences, and a selective smattering of academic studies to detail how a range of artists ushered in new forms of verse composition.

We also know many musicians and poets, as well as a healthy

handful of people who work with both forms. We’re both active writers, and Mike

has been a professional songwriter and musician for three decades.

What surprised us most was the depth of many songwriters’ engagement with

poetry in specific and literature in general. This phenomenon started to become

widespread during the 1960s, but extends to the present.

Part of our case for poetic song verse as a genre is the emergence of rock as pastiche, the combining of disparate materials, forms and genres, often without regard to their individual rules of usage.

Thus poetic song verse is boundary-hopping. Or perhaps more accurately, boundary-leveling. Almost any art form’s success depends on understanding—whether intuitively or intentionally—one’s historical moment: when exactly to ignore or break the rules.

Punk, rap, and hip-hop challenged and extended rock and poetic song verse. The closing decades of the 20th century and the opening decades of the 21st have witnessed a continuation of poetic song verse in rock and other modes.

Green Day, Titus Andronicus, the Mountain Goats, the Avett Brothers, Anaïs Mitchell, Janelle Monáe, the Drive-by Truckers, the North Mississippi Allstars, and other relatively recent well-known acts have made lyrically ambitious albums in the 21st century, but several of the most successful recent ventures into poetic song verse have come from lesser-known bands, like AmeriCamera (it’s worth recalling the blues’ humble origins and that literary modernism sprang from a small coterie of young artists publishing in little magazines in the 1920s).

Q: Which other recent artists do you see carrying on this

tradition?

A: Lucinda Williams, Steve Earle, Kendrick Lamar, Norah Jones, Dave Grohl,

Fiona Apple, Lorde, Aimee Mann, Fantastic Negrito, Josh Ritter, Lyle Lovett,

Luther Dickinson, Jason Isbell

Q: What are you working on now?

A: We edit a feature, “Hot Rocks: Songs and Verse,” for Literary Matters, a

journal of literature and art, and we’ll keep thinking and writing about

music’s relationship to other art forms, especially literature.

Our new book project, tentatively titled Ralph Ellison, Robert Penn Warren, and the American Century, is just getting off the ground. It’s about American culture during the middle of the 20th century.

Ellison is best known for his groundbreaking novel, Invisible Man, but he also wrote a large handful of essays about music and essays about race. Warren is best known for his great novel All the King’s Men, but he also wrote poetry, histories, literary criticism, and books on race relations.

Ellison was Black and Warren was white, and they were raised in segregated societies, but came to become close friends and to see themselves as engaged in similar struggles and artistic enterprises. We want to tell their stories, and to examine how their stories help us understand what our society is experiencing today.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: We wrote the book we wanted to write. Poetic Song Verse: Blues-Based Popular

Music and Poetry was a labor of love. We wanted to make it readable without

yielding any ground intellectually.

Our goal was to balance historical details and analysis of particular songs with accessibility, and to create a lively, intelligent, and cohesive narrative that provides readers with an overarching perspective on the development of an exciting, relatively new literary genre: poetic song verse.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment