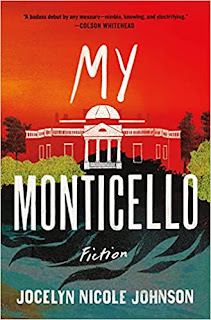

Jocelyn Nicole Johnson is the author of My Monticello, a new collection of stories and a novella. Her work has appeared in a variety of publications, including Guernica and The Guardian. A public school art teacher, she lives in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Q: Over how long a period did you write the stories and the novella in this collection?

A: I wrote the collection, bit by bit, roughly between 2015 and the spring of 2020, while working full time as a public school art teacher.

Q: In a New York Times interview, you said, “I had a moment after I published ‘Control Negro’ where I realized how that story and other stories I was working on were connected. And that was through this idea of place, through this idea of Virginia. And through the lenses of racial and environmental anxiety.” Can you say more about Virginia's role in the book, and about how important setting is in your writing?

A: There’s a way in which Virginia should feel unequivocally like home to me. I was born and grew up in Northern Virginia. I went to college in the Blue Ridge Valley, taught in Arlington, and started my own family in Charlottesville. I've lived in Virginia my whole life.

But for me, there has always been a barrier to my experience of Virginia as home.

This feeling was brought into sharp relief by local events during the time I was writing My Monticello, from the bloodying of a Black University of Virginia student by uniformed officers, to the deadly Unite the Right rally in 2017, where white nationalists wielding guns, torches, and flags of past genocides shouted things like “Into the ovens” in public spaces in my community.

In the year that followed, I learned more about the history of local black communities, which included systems of racism and brutality going back to the times of our local founding father, Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson's plantation home, Monticello, sits on a hill about a 10-minute drive from my home.

The stories in My Monticello are set in the physical and emotional landscapes of Virginia, and circle around questions of belonging, home, and history.

Q: How was the book's title (also the title of the novella) chosen, and what does it signify for you?

A: The original title for the collection was the name of the second story, “Virginia is Not Your Home.” But later, when I wrote the novella, its title read like a declaration.

The “My” refers to the anxious claim of the novella’s narrator, Da'Naisha Love, who is a hometown girl, a student at the University of Virginia, and an imagined Black descendant of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings.

In a near future time of unraveling, DaNiasha, her grandmother, and a diverse group of neighbors flee marauding white supremacists and take refuge in Thomas Jefferson's historic plantation home turned tourist site.

The title “My Monticello” is a challenge for myself, and readers, to expand our notion of belonging, ownership, and stewardship.

Q: The New York Times review of the book, by Bridgett M. Davis, says of the novella, “Up close, we cannot ignore our present-day complicity with history even as the novella moves propulsively toward tomorrow’s inevitability.” What do you think of that description?

A: In his 1782 book, Notes on the State of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson was already thinking about the apocalyptic endpoint of the violence and exploitation of black people.

He wrote, “Deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained; new provocations; the real distinctions which nature has made ... will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race.”

My novella examines the physical and psychological costs of creating and exploiting “the other.” It is, in part, a cautionary tale. If we continue to dehumanize certain communities, and divest our shared infrastructure, and ruthlessly exploit the ground we all stand on, this is a window into how a future might look and feel.

The novella---and the whole collection---also offers hope. As my characters struggle and strive, there are moments of beauty, of connection, of joy. There are always opportunities to do better, to invest, to listen, to recognize our connection to everything and everyone, to begin the work of repair.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I always have a few stories going. I have a couple of longer projects for which I'm collecting ideas, and dreaming!

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment