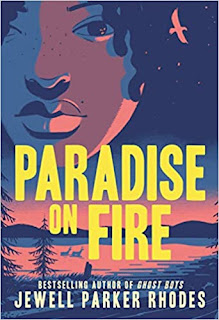

Jewell Parker Rhodes is the author of Paradise on Fire, a new middle grade novel for kids. It focuses on a group of kids on a wilderness program who are forced to contend with a wildfire. Rhodes's many other books include Black Brother, Black Brother. She is the Virginia G. Piper Endowed Chair of Creative Writing at Arizona State University, and she lives in Seattle.

Q: You’ve said that part of the inspiration for Paradise on Fire came from a group of kids you met in Wyoming. Could you describe how that interaction led to this novel?

A: I draw on a lot of my life experience for writing my books. Things will rattle around in my head. Being in the Pacific Northwest and California as an adult, there’s still not a large minority population.

I was taken aback by seeing a whole row of African American young teens at a literary conference. I found out about City Kids DC. They have sponsors in Wyoming who own ranches, and they’ve partnered for kids to have a wilderness experience.

The program draws from 6th grade to high school. It’s a way to make kids more invested in school, college, and career. Experiential learning can help with confidence.

Kids are rewarded for math and verbal [abilities], but the idea that learning to do different activities in nature is bolstering your identity made sense to me. I had seen it with my daughter in Girl Scouts.

The programs continue throughout the year, and the kids become mentors to younger kids. There’s a nurturing of kids with book learning and nature learning.

With Girl Scouts, the minority representation is still below what it could or should be. African American Girl Scout troops I know in Georgia and D.C.—a lot of the experiences aren’t in nature but in the community, doing book drives for kids in Africa.

Maybe there’s a visceral sense that we all have to prove ourselves, and pull on the resources within yourself. The back of the book has statistics about national parks—poor and minority kids don’t get to appreciate that.

When I experienced the smoke from the wildfires over the last four or five summers, it naturally came together: How do I get a young Black girl challenged by nature?

Q: In the book’s afterword, you write, “Paradise on Fire, I hope, will be a reminder to everyone that human action can slow climate change and help prevent forest fires.” What do you see looking ahead when it comes to climate change?

A: I do see that we’re raising a generation of children much more sensitive to habitats. They want to preserve more acreage, trees, forests.

The idea of getting more kids involved in environmental action—recycling, planting trees, volunteering with nature conservancies, slowing climate change—I hope with my writing to [raise] activist young kids.

With our generation, it was more lip service than actual change. With Greta Thunberg’s, they see it as a social justice issue with an impact on their future.

I also like the idea of students being aware of the mental health connections. Thirty minutes in nature can help your mental health.

Q: The New York Times review of the book, by Jennifer Medina, says, “Addy is a heroine any reader might aspire to be, a teenager who learns to trust her own voice and instincts, who realizes that fire can live within someone, too.” What do you think of that description, and how did you create Addy?

A: I thought that description was very interesting. I hadn’t thought of it that way, but if you think of fire, the connection to the story around emotions and passion is Addy.

Her emotions are [driven] by fear, but at the end of the book she transcends all that and becomes more aware of her capabilities. She takes on ownership of her friends, her community, her social relationships. She moves from being fearful to being a passionate leader.

I think of boy survival stories. Brian in Hatchet does it all for himself. In Lord of the Flies, they don’t even make it that far. In a woman’s survival story, of course she would take her friends with her. She was guided by a matriarchal elder.

I don’t sit down and think about [creating a character like Addy]. I can’t start without a first line. I had Grandma Bibi talking to her, and Addy on the plane. The whole idea of her flying and thinking about how she can escape the airplane came to me.

Q: The Kirkus Review of the book calls it “A heart-pounding read that imparts both a healthy fear and a deep appreciation of nature’s power.” What did you see as the right balance between fear and appreciation as you were writing the book?

A: I’m always looking for balance, yin and yang. For each moment of intense fear of the wildfire, that fear is there, but because of nature, there’s also regeneration.

At the point when you’re on the roller coaster and it’s going to be scary, I step up to that in the chapter where the students are learning their skills. I do think there’s straight-on fear: Are we going to survive?

Typically in my books, always after we’ve gone through an incredible time, we’ll pick ourselves up and start over again.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I’m finishing a new book. I’m not allowed to announce it yet. It’s a retelling of a children’s classic that’s over 200 years old. It’s been interesting, making historical literature relevant for today.

It involves African American and indigenous people’s rights. It also involves skateboards, and I don’t know anything about skateboards. It exploded during the pandemic among rural and inner city minority communities. There are more girls doing it. Here I am, trying to watch YouTube videos!

I like writing because it keeps me learning and takes me in so many different directions. You can have so many lives. I’m writing from my acting background, I’m acting all the parts. I’m a passionate writer. If the characters are not passionate, I can’t act with them.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: Sometimes I’ll put little things in my books that I know no one will get but me. I was looking for Addy’s name. I wanted her to be African/African American. Aduago, “daughter of an eagle,” is a brown eagle famous in Nigeria. They have terrific conservation and forests, and used to have festivals of eagles. Eagles have stopped coming since climate change.

Mexico and Germany also revere the eagle. The idea is comparable with our bald eagle. There’s a global connection. The eagle is an American thing, but it’s also representative of her Nigerian heritage. And of how animals in various parts of the world are being lost.

I’m always writing for teachers to teach my books, or parents to discuss them with their kids. They could look up the eagle, the well-being of the eagle, how a forest declines. In the hands of a great teacher or a parent doing activities with kids, there are ways to have kids do things inspired by the book. It is intentional.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb. Here's a previous Q&A with Jewell Parker Rhodes.

No comments:

Post a Comment