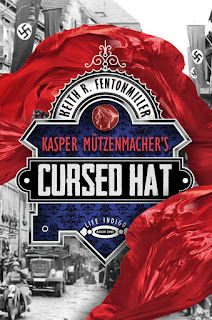

Keith R. Fentonmiller is the author of the new novel Kasper Mützenmacher's Cursed Hat. His work has appeared in Stonecoast Review. He is a lawyer in Washington, D.C., and he lives in Kensington, Maryland.

Q: How did you come up with the idea for your novel?

A: A complete answer to this question would require a depth

of psychoanalysis more appropriate for a Neurotics Anonymous blog, so I’ll try

to keep it short.

I trace my novel’s inspiration to two sources. First, my

late grandfather, Dr. Meryl Fenton, whom we all called Papa. Like my novel’s

protagonist (Kasper Mützenmacher), Papa was a squat fellow with a big nose. Unlike

Kasper, Papa didn’t have a facial scar, nor was he cursed (so far as I know).

Papa always reminded me of Zoot, the jazzy,

saxophone-playing puppet from the Muppet Show, which may explain why Kasper

loves jazz and plays the cornet. It also may explain Kasper’s overwhelming

sense of being manipulated like a puppet, whether by Nazis, women, his

children, or Fate.

Second, there was an incident when I was 10. Growing up, my

family had a Sunday breakfast tradition with bagels, cream cheese, lox, eggs,

and—the best part—Sara Lee pecan coffee cake.

One day, my dad carved out the coffee cake’s center for

himself, leaving a thin, bready rind for everyone else. I remember thinking, Is

he having a stroke? Is he possessed? Turns out, he was just indulging a whim.

(Full disclosure: My father claims not to recall the incident.)

Granted, as childhood traumas go, a gutted coffee cake is

pretty mild stuff. Yet it’s stuck with me all these years because of what it

symbolizes—the psychic void inside us all, a void we spend a lifetime trying to

fill. So it was only natural I wrote a novel about cursed hat-makers, right?

Right? Of course, right. Think about it: What’s a hat but fabric wrapped around

an empty center?

Q: Did you need to do much research on the historical periods

you cover in the novel, both in Germany and the United States?

A: I read many books to get a sense of what life was like

for Germans, and German Jews in particular, during the ‘20s and ‘30s, and for

black Detroiters during World War II.

I also visited the Library of Congress to view old issues of

the sci-fi magazine Amazing Stories, elements of which made it into the novel.

I also reviewed century-old issues of the music magazine Metronome, which

documented the evolution of ragtime into jazz and the shifting attitudes toward

that syncopated, improvisational musical form.

Through Google Books, I discovered early 20th-century books

about millinery, which proved invaluable for the scenes where Kasper teaches

his children to make hats.

Q: The book incorporates both history and fantasy. What did

you see as the right balance?

A: History and fantasy aren’t necessarily oppositional story

elements. This is my modus operandi: whatever elements an author

invokes—whether it’s history, fantasy, absurdity, romance, violence, humor—and

to whatever degree he or she invokes them should serve the narrative, not the

other way around.

The Cursed Hat is primarily a family saga about the fluidity

of tradition, faith, and identity. The curse, the wishing hat, and the

historical settings were means to instantiate these themes through the

struggles of the Mützenmacher family, hopefully in a colorful way that does not

digress from the core narrative.

I invoked Greek myth because it taps into the psychological

archetypes that both animate our personalities and embody the communal schema

that, for better or worse, define families and cultures across generations.

The horrific events of the mid-20th century likewise possess

a mythical, almost unreal quality for me. I was born long after World War II. I

am temporally and geographically separated from the Nazi genocide and the race

riots that plagued American cities. My ancestors endured no losses of lasting

significance during that era.

Nevertheless, those events haunt me in a very palpable way:

I owe my very existence to accidents of geography, genetics, and good timing.

As far as I’m concerned, the line between history and myth (a type of fantasy)

is blurry and arbitrary, assuming such a line even exists. This is certainly

the reality that the Mützenmachers occupy.

Q: Did you know how the book would end before you started

writing it, or did you make many changes along the way?

A: Kasper Mützenmacher’s Cursed Hat began as a single book

set in the present. The events of the story were no more than a few paragraphs.

After years of expansion and tinkering, those events morphed into Book One of

the Life Indigo series.

Although I knew how I wanted to end the series, I did not

know how I would end the Cursed Hat when I started writing. The key was

figuring out the story I was trying to tell.

Ultimately, I focused on one theme: the persistence of

family tradition. Like the curse in the story, traditions—whether religious, cultural,

or familial—have a powerful binding effect. But when traditions are perpetuated

mindlessly, selfishly, or demagogically, they become vice-like, oppressive.

The English word “tradition” comes from the Latin word to

transmit, hand over, or give for safekeeping. That definition presumes the

existence of a willing recipient, which is not always the case with traditions,

let alone curses.

The intended recipient may balk. He may see resistance as

his only option, even his obligation. As German-Jewish philosopher Walter

Benjamin once said, “In every era the attempt must be made anew to wrest the

tradition away from a conformism that is about to overpower it.”

This is the tension with which each Mützenmacher generation

must grapple. Once I teased out this struggle, the character arcs for Kasper

and his grandson Chance became clear, and the ending I ultimately chose felt

right, if not inevitable.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I am working on Life Indigo Book Two: Memoirs of a Water

Nymph. I hope to publish it by late 2018. I’ve also been writing shorter

pieces. My short story, "Non Compos Mentis," was recently published in the

Stonecoast Review. I’m honored that the journal nominated the story for a

Pushcart Prize.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: A few weeks ago, my wife discovered the stiff, lifeless

body of Butter, my daughter’s goldfish, on the kitchen floor. Evidently, it had

leaped out of its aquarium during the night. It happened to be the same day my

book came out. What’s the significance of this piscine suicide? There’s only

one logical conclusion: Buy my book—if not for me, do it for Butter.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment