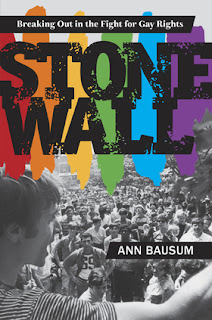

Ann Bausum's new book for older kids is The March Against Fear: The Last Great Walk of the Civil Rights Movement and the Emergence of Black Power. Her many other books include Stonewall and Freedom Riders. She lives in Wisconsin.

Q: Why did you decide to focus on the March Against Fear?

A: This was history I had a glimpse of as a child—it was

partly to complete a loop back to my childhood, and explore the history that

seemed so perplexing when I witnessed it. It was a memory without context into

my adult life. I didn’t realize it was this march I had seen.

It was partly to satisfy the childhood [memory] and partly

to understand what happened to the civil rights movement, and use this endeavor

as a way to look at what was going on with the civil rights movement

mid-decade. Having written about it already, this felt like a missing piece.

Q: How did you research the book, and was there anything

that especially surprised you?

A: The research was extensive, including a drive in 2012

which retraced the route of the March Against Fear, going South and then back

North the way [James] Meredith walked the next year. I’d done that with other

history. I find it very important to have that physical connection, seeing the

courthouses and campgrounds where the events had taken place.

It was a lot of archival work, especially in Memphis, where

there was a particularly strong photo archive. Memphis was the hub for covering

events like the March Against Fear. I discovered two more [archives] which had

a wealth of photos to study. The photos are important.

I interviewed James Meredith and a historian writing an

adult book about the history. I worked with a lot of eyewitness accounts

collected at the time. There’s a huge trove of newspaper coverage of the event.

Then there are historical analyses done as well.

Q: And did you find things that particularly surprised you?

A: Always! There always are surprises, that’s what makes it

so fun even when you’re researching grim history.

I was unaware of the attack in Canton, [Mississippi,] a

rather major civil rights infringement where a nonviolent protest was

confronted by state troopers who proceeded to clear the ground by teargassing

people, beating and dragging them from the property. I was in my 50s and hadn’t

learned that. It seemed buried and forgotten. Events like that need to be

brought [to light].

Q: What do you see as the role of James Meredith?

A: It’s an interesting role and creates a challenge. In some

ways he’s the main character, but then he’s absent because he was injured. It

creates a challenge to introduce him to readers and hopefully not leave them

frustrated when he exits the stage.

History is full of more accidents than we give it credit

for. His role was really accidental because of the transformation of being shot

trying to do this pretty simple walk, until you place it in a racially charged

context.

Had he not been attacked, it wouldn’t have turned into what

it turned into. It wouldn’t have had the consequences it had with the civil

rights movement coalescing to complete it.

Q: How would you describe the impact, and the legacy, of

this march?

A: It’s so complicated. It had an impact in so many arenas.

It had an impact on the civil rights movement—it has as much an effect of

weakening it than as strengthening it. They pulled it off despite having

multiple organizations and multiple points of view.

The fact that the walk was so complicated--you layer in the

concept of Black Power. It had not reached the national stage prior to the

walk. That created an illusion if not [of] something stronger, of a rift in the

civil rights movement…[the] impact was of mixed benefit.

To raise the idea of empowerment of the African American

population—there was an opportunity to make that case, but it didn’t land the

way it was intended.

We tend to think of impacts being positive,

game-changing—impacts are much more complicated than that. [With another

example, one could] say, Wow, we walked from Selma to Montgomery and then the

Voting Rights Act was passed—that’s much more cause and effect.

With this, [the idea is], We spent three weeks pulling off

an incredible march, thousands of people walking in the steps of one, yet it’s

not clear what the lasting impact was. Sometimes history doesn’t give you that

uplift.

Q: So does it have a legacy today?

A: It feels that way to me. Particularly when I was working

on it in 2015 and we were having a succession of events that helped feed the

Black Lives Matter movement with the random victimization of African Americans

and police confrontations.

It felt deja-vu-ish almost that there was an unfinished

legacy, what have we been doing for the last 50 years, we’re right back there

raising the same issues…

I’m looking back at it today and noticing even things like

the discussion in the book of how conspiracy theories were growing—and there’s

another echo from past to present.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I’m returning to gay rights history. I had done a book on

the Stonewall riots and had become so interested in the history of AIDS. That’s

what I’m doing, for teens on the history of AIDS.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: I just am so moved by the photo archives. I used them to

mark the 50th anniversary [of the March Against Fear] last summer. I did daily posts on Facebook and Twitter. Two of the archives are very accessible to the

public, so I was able to share them.

One other detail that might be of interest is the award I'll be receiving next spring from the Children's Book Guild of Washington,

D.C. This organization commends the body of work by a children's nonfiction

author each year, and my work is being recognized next year.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment