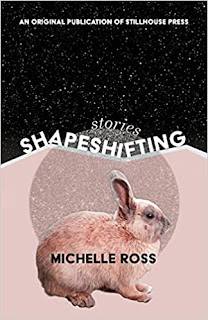

Michelle Ross is the author of the new story collection Shapeshifting. Her other books include There's So Much They Haven't Told You, and her work has appeared in a variety of publications, including Alaska Quarterly Review and Colorado Review. She is fiction editor of Atticus Review, and she lives in Tucson, Arizona.

Q: Over how long a period did you write the stories in your new collection?

A: First, thank you so much for talking with me, Deborah!

I wrote most of these stories over the course of about five years. The one exception is “Life Cycle of an Ungrateful Daughter,” which I first drafted so many years ago, I’m not sure how old it is. Maybe 15 years old? Maybe 20? This was back when I hadn’t published but a few stories.

I know I submitted “Life Cycle” to at least a few journals because I found a handwritten rejection from Zoetrope in an old file folder of paper rejections from back when submissions all happened by mail.

At some point, I put the story away—I’m not sure why except that it feels more autobiographical than most of my fiction and maybe that made me feel uncertain about it? I forgot all about it for years.

A friend reminded me of it a few years ago, and I dug it up, polished it, and submitted it again. Also, I realized it belonged in Shapeshifting.

Q: In a review of the book on Mom Egg Review, Carla Panciera writes, “In Ross’s world, motherhood is the ultimate shapeshifter, beginning in pregnancy...” How was the book's title (also the title of one of the stories) chosen, and what do you think about mothers as shapeshifters?

A: I think all humans are shapeshifters (I wrote about this some in my Research Notes for Shapeshifting, published in Necessary Fiction), but mothers especially. Pregnancy is, of course, a literal transformation of the woman’s body into something alien.

But more importantly, motherhood has the power to erase who the woman was before motherhood. It’s not just that the child sees her only as Mother, but so do many of the other people in her life. Even she may struggle to see herself as something other than Mother.

The book’s title comes from the story titled “Shapeshifting,” only at the time that I titled the book, that story had a different title.

The pregnant protagonist in the story says that as a kid she liked the idea of being a shapeshifter but that it didn’t occur to her that pregnant women are shapeshifters, too: “Shapeshifting isn’t the way I’d imagined it. I’d always pictured myself behind the wheels of other bodies I assumed. This is the opposite. I’m the wheels, not the driver.”

I wasn’t yet finished writing all the stories in this book when I decided that Shapeshifting was the perfect title. When the editors at Stillhouse Press suggested I retitle this story, which had been titled “Gestation,” to match the book’s title, I agreed that it was a better title for the story, too.

Q: I asked you about this in our previous Q&A too--how did you choose the order in which the stories would appear?

A: The editors at Stillhouse, and the contest judge, the amazing Danielle Evans, helped determine the order of the stories. The manuscript I submitted opened with “A Mouth is a House for Teeth,” for example, and they suggested it should be the closing story instead.

The editors pretty much completely rearranged these stories. I think they were right, though. This order is now so familiar to me, I struggle to remember the original order of the stories without looking back at that earlier draft.

Q: Another review of the book, by Kathryn Ordaway for The Masters Review, says, “Some of Ross’s best moments are dropping tidbits of information that make the stable become unsteady. She is expert at dispensing unexpected information at just the right moment.” Is that something you're aware of doing as you write?

A: I think carefully about what readers need to know and when they need to know it, as well as about how the arrangement of sentences affects tension, characterization, theme, and rhythm. I’m trying to get maximum effect out of the structure.

My good friend and writing collaborator, Kim Magowan, has often commented on this tendency of mine to constantly rearrange sentences and paragraphs like I’m putting together a jigsaw puzzle. The longer a story is, the more complicated this question of when to reveal information can become.

One of my favorite revision exercises for longer stories is to cut them up and physically move around the pieces. Even in flash fiction, however, I find that rearranging the pieces is often a part of the revision process for me. Sometimes a story will feel so close but not quite right, and all I do is move around a few sentences and, just like that, the story is done.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: What I’ve been spending most of my time on lately is a book that centers on a fictional Texas high school. I’m particularly interested in exploring the intensity—and sometimes barbarism—of female friendships.

I have a few other projects in the works, too, including a collection of stories that reimagine characters from classic horror movies.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: My flash fiction collection, They Kept Running, won the 2020 Katherine Anne Porter Prize in Short Fiction and is forthcoming in early Spring 2022.

Also, Kim Magowan and I are currently trying to find a home for our collaborative short fiction manuscript, a collection of 24 stories—a mix of longer fiction and flash fiction. It was a finalist for the Hudson Prize and the Non/Fiction Collection Prize, but no takers yet.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb. Here's a previous Q&A with Michelle Ross.

No comments:

Post a Comment