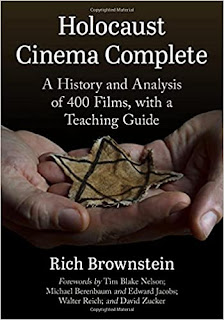

Rich Brownstein is the author of the new book Holocaust Cinema Complete: A History and Analysis of 400 Films, with a Teaching Guide. He is a lecturer for Yad Vashem's International School for Holocaust Studies, and his work has appeared in a variety of publications, including The Jerusalem Post and The Forward.

Q: Why did you decide to write this guide to Holocaust films, and how did you choose the films to include?

A: Holocaust films are my avocation. To write a book about what I do was just a matter of time.

The specific reason was that I was lecturing at Yad Vashem and talking about The Grey Zone as the greatest Holocaust film ever made, and my students said, “Why don’t you write about that?”

I thought it would be best to have a set of recommended films of the 443 I consider narrative Holocaust films. I wrote reviews of 50 that I most recommend. I also wrote a chapter about pedagogy and have chapters about the history of Anne Frank films and Schindler’s List, though I don’t recommend it [Schindler’s List].

I wrote a chapter about how hard it was to view Roman Polanski’s The Pianist in terms of its having been made by a child rapist.

Q: Why don’t you recommend Schindler’s List?

A: I believe in economy in filmmaking. It was an hour-and-a-half story [Steven Spielberg] was able to turn into a 3¼-hour film. As Claude Lanzmann said, we don’t need a film about a Nazi saving Jews from the Nazis. It turns the whole thing on its head.

Many films were made about people who were not Nazis who saved more Jews than Oskar Schindler did. There are movies about Jews saving Jews. [Spielberg] took a subject only he would dare to use to rehabilitate the scum of the earth, and he did it. It doesn’t make it a great movie.

I have to say I have great respect for Steven Spielberg as a person. He turned over the profits from Schindler’s List and made the Shoah Foundation.

Q: You refer to The Grey Zone as "the greatest Holocaust film ever made." Why do you think that's the case?

A: It’s about the sonderkommandos who manned the death chambers. There are no heroes in it. These people are flawed. They are real.

The director was not turning them into pedestalled characters of the Holocaust, like in Uprising or The Zookeeper’s Wife. Virtually every film takes the victims of the Holocaust and turns them into unflawed heroes. Here we see people acting as they were.

The story is a little-remembered revolt at Auschwitz-Birkenau where the sonderkommandos destroyed two of the four gas chambers.

The larger answer is by the time the film was made, the director, Tim Blake Nelson, had learned what had worked and not worked in the previous 50 years of Holocaust filmmaking. Let the actors speak as they speak, not with fake accents. He stuck to the truth. It doesn’t do any good to put a Holocaust fantasy together.

Q: You divide the films into four eras: Postwar, Commercial, Mature, and Consolidated. What distinguishes each era from the others?

A: The first era is what you’d expect from the beginning of any art form, especially when there’s very little information available. The first era [Postwar] was about baby steps. There were only about three Holocaust films each year in that period.

Some important movies were made: The Pawnbroker, Cabaret. Famous films like the 1959 version of The Diary of Anne Frank, an artistically regrettable film. There were errors made during that period because they didn’t have the information.

The postwar period ends in 1973 with the advent of television—QB VII, War and Remembrance. Production doubled to six a year. This lasted through 1996, and includes Schindler’s List. The two most important of the period were Schindler’s List and the Holocaust miniseries. They were still finding their way.

The mature era includes 1997-2013, and there were 8½ films made per year. This is when the great films were made. There were great films before and after, but most were made in this period.

Now, we’re in the consolidated era. Almost half the films that come out are remakes. There’s a lot of repetition. I’m not going to suggest remakes are worse than the original, but there aren’t a lot of new stories. There are over 11 made per year.

Q: What do you hope readers take away from the book?

A: Specifically which Holocaust films are good or bad, which can be used in education, the history of Holocaust filmmaking.

Critical thinking is essential to everything we do—politics, art, and everywhere in between. We need to look at something as celebrated as Schindler’s List and be able to tell the truth about it. It’s not a film that’s representative of the Holocaust.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: The first book didn’t have reviews of every Holocaust film available, only 50. The second book will be reviews of every Holocaust film, closer to 400.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: I love films and want every film to succeed. I hope the best for them as I’m watching. For me to dislike a film is not because I’m a curmudgeon, it’s because they’ve given me good reason to dislike them.

The book is made to be read sequentially. It tells a story. Only one of the chapters is a reference chapter. The others tell stories about aspects of Holocaust filmmaking.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment