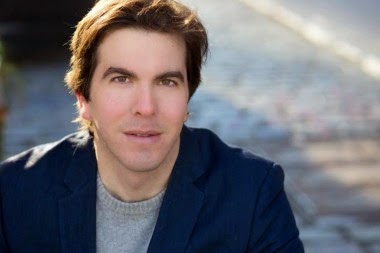

Jacob Silverman is the author of the new book Terms of Service: Social Media and the Price of Constant Connection. His work has appeared in a variety of publications, including The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times, and he lives in Brooklyn.

Q: Why did you decide to write about social networking?

A: The very practical answer is that someone thought there

was an opening for books about social media. People were doing interesting

writing--journalists, academics…[but] I didn’t really feel like someone was

writing about it from the perspective of a cultural critic.

Q: You write, “Popular tech writing tends to fluctuate

between the two poles of Luddite rejection and unvarnished techno-utopianism.”

Where would you place yourself on that spectrum?

A: I think I’m definitely more on the skeptical side. On the

other side, I’m writing about [it] because I’m immersed in the products. But if

I’m being honest, I think we need to be more skeptical in our technological

writing.

Q: Why?

A: I think the landscape has changed somewhat in the last

couple of years. You see more technological criticism, but there’s just been so

much enthusiastic non-critical coverage of what tech companies do…

I think it’s also very easy to approach the stuff, and be

enthusiastic and be a booster. That’s how a lot of people see these companies.

The heads of companies are celebrities, every bit of news they make is reported

on feverishly. We need to get away from this, and look at what the companies

do, what their labor practices are…

Q: You use the term “churnalism” in the book. How do you

define that, and what has social media done to journalism?

A: I see churnalism as what has come to replace the daily

news cycle—the constant turnover of new material, and a lot of it comes from

the fact that journalists are now supposed to be always on, always producing.

There’s slang that some journalists use—“feed the content

beast.” There’s a cycle in which people are looking for something to write

about or for an angle on an established news event…they have to find some take

that differentiates themselves from the others.

What happens with the idea of churnalism is that it becomes

like social media. It’s always on, it’s always being refreshed and updated. The

most recent thing is always passé and needs to be updated.

Social media provides journalists with a false sense of

their audience. It’s their own kind of bubble where journalists live.

Everyone’s reading you and interested in X subject because it’s trendy, but it

doesn’t speak to the newsworthiness of the subject.

Q: In your discussion of privacy, you write, “Privacy isn’t

about hiding information; it’s about having the right to choose when and how

you reveal information.” What has social media’s impact been on that type of

privacy, and what do you see in the future?

A: I’ve come to the conclusion that there are two real types

of privacy. I still agree with the definition in the book. [There] is a kind of

privacy where you want control with what other people know about you; it’s

associated with oversharing and posts on Facebook [that] anyone can read….

The other type is data privacy. Social networking has

undermined both. Data privacy looms as a larger problem. We’re still getting to

understand how data is being collected and how it’s used…it’s very difficult to

stop….

Privacy runs along two tracks—we are going to assess how

much control we have, and the very systems that are harvesting our information….The

attitude companies are taking now is that they are safe repositories of our

information, but that undersells the issue….

Q: What surprised you the most in the course of researching

this book?

A: I was shocked at the scale of data collection going on.

In some way I tried to resist the idea that data was becoming a commodity, like

oil…

I was also surprised at the various ways in which things we

think of as internet-only are entering other areas of life—systems that track

customers coming into a store, trashcans with sensors…surveillance is entering

everyday life, not just online…

Q: Has your own use of social media been affected by your

work on the book?

A: I don’t know if it’s always for the better. It’s hard for

me to use the same services now with the same sense of ease. I deleted my

Facebook account while I was writing the book. I still use Twitter somewhat but

I find myself a lot more self-conscious.

What’s changed for the better is that I draw more

distinctions between public-facing social media and more private forms of

communication—e-mail, instant messaging. For me, I prefer the intimacy and

privacy of exchanges where it’s just me and another person in a chat box or

e-mail.

With young people today flooding into messaging apps, I think

young people have a similar desire—to communicate with people one-on-one with

some sense of intimacy and privacy. I wonder if the era of big public-facing

social networks might be an anomaly….

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment