Counting down the top 10 most-viewed Q&As of 2024--here's #7, a Q&A with Elizabeth Graver first posted on July 14, 2023.

Q&A with Elizabeth Graver

|

| Photo by Adrianne Mathiowetz |

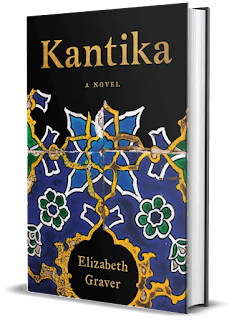

Elizabeth Graver is the author of the new novel Kantika. Her other novels include The End of the Point. She teaches at Boston College.

Q: You’ve said that Kantika drew on the experiences of your maternal grandmother--why did you decide to write this story?

A: I was drawn to how the story connected to my own personal roots, as well as to vanishing traditions and to the experiences of exile and migration in our current times.

In some ways, though, the more salient question is why did it take me so long? I recorded my grandmother Rebecca telling stories in 1985, when I was 21. She died in 1992, but it took me until 2014 to turn to a project inspired by her life.

At that point, I was motivated partly by the fact that my mother and her remaining siblings were entering their 80s and 90s. I wanted to sit down with them and ask about their childhoods, and I wanted to write something that they’d be around to read.

I’d already published four novels and finally felt confident enough to take on a project of this breadth and depth. The story is full of languages I don’t speak and cultures I didn’t know much about going in.

The subject matter was at once far afield and, in its connection to my family, very close to home—a daunting combination. Once I started reading, traveling, interviewing people and dreaming my way inside characters, I was hooked.

Q: How was the book’s title chosen, and what does it signify for you?

A: The title, Kantika, means “song” in Ladino or Judeo-Spanish. Ladino was the language spoken by the Sephardic Jews who originated in Spain and were expelled during the Spanish Inquisition. In the former Ottoman Empire, it took the form of pre-expulsion Spanish combined with Hebrew, Turkish and other contact languages. It was my grandparents’ and mother’s first language, spoken mostly in the home.

Today, it’s an endangered language that has survived in the form of folktales, prayers, songs, and adages. It offers a window into the richly textured world of the Sephardim.

I wanted the title to be in Ladino both as a recuperative gesture towards this disappearing language and because I liked the idea that many of my readers would not understand the title’s meaning right away. Most immigrants live among and between languages; the crossings can be both challenges and gifts. The title both invites you in and asks you to cross over.

In terms of the meaning of the word “kantika”—song—Rebecca loves to sing and carries songs with her when she must leave so much else behind. And I view the novel itself as a kind of song, or even a duet—between the past and present, history and fiction, my grandmother and myself.

Q: In a New York Times review of the book, Ayten Tartici writes, “In Graver’s

vision, migration is never simply a one-way street from the Old World to the

Promised Land. Rather, her characters zig and zag, doubting, retracing and

remembering the places that have shaped them.” What do you think of that

assessment?

A: I loved Ayten Tartici’s review; she really understood the nuances of my novel. That zig-zagging is exactly right. Memory isn’t linear, of course, but I was also interested in how the past can return in different forms. The family has several beautiful gardens in Turkey.

In Spain, their circumstances are much reduced, but Rebecca’s father brings seeds and bulbs to Barcelona and sinks his hands into the soil. Some plants take while others fail. Later, in America, Rebecca does the same thing on a small patch of land.

There’s so much loss in the book, but I was also interested in how things remain or return, often in ghostly or refigured forms. Rebecca’s parents talk to her across the distance, even after they’re no longer among the living. I included family photographs in the novel, another way to embody some of that zig-zagging. A photo isn’t a person or even an impartial rendering of one, but it’s something, it’s a trace.

Q: What did you see as the right balance between history and fiction as you wrote the novel?

A: I want to weave a spell, for the reader to be inside the story, living it, but with this book, I was also interested in signaling that this particular story has a relationship to the real—another function of the photographs.

In doing research, I stumbled upon a 1929 Spanish propaganda film about Sephardic Jews that contained unattributed footage of my family. In Kantika, the filmmaker, a future Fascist, comes to the house to film Rebecca and her children. That’s perhaps the most concentrated example of history entering the house.

In a wider way, it mattered to me to get the history right in terms of key events. Whether it’s the Spanish Civil War, World War II, or US immigration policy in the 1930s, historical events, going all the way back to the Spanish Inquisition, are responsible for the diasporic path this family takes.

As a novelist, I try to avoid bogging down the prose with chunks of fact. The challenge was to figure out what it meant to live through big events in a granular, daily way. The benefit of hindsight means that at any given moment, I might know more than the family about what’s happening on the world stage, but they’re living it; it’s in their bones.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I don’t like to talk about my work in detail in the early stages, so I’ll just say that I’m circling around a project that might be nonfiction connected to my late father. I really know very little at this point, and I’m not in a rush. I actually love this stage, full of not-knowing and possibility, but to describe it in anything but the broadest way can knock me off course.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb. Here's a previous Q&A with Elizabeth Graver.

No comments:

Post a Comment