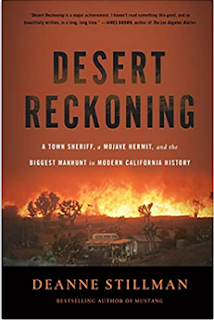

Deanne Stillman is the author of the book Desert Reckoning: A Town Sheriff, a Mojave Hermit, and the Biggest Manhunt in Modern California History. The book was published 10 years ago. Stillman's other books include Twentynine Palms, and her work has appeared in a variety of publications, including the Los Angeles Times and The New York Times.

Q: Looking back at your book Desert Reckoning, which first came out 10 years ago, what stands out for you?

A: What stands out is how the incident that I wrote about, a hermit who kills a cop with an assault rifle that he has hidden away in his trailer, has all of the DNA of many of the incidents that have gone on since - mass shootings, "random" attacks, even Malheur in a way.

And by that I mean that the hermit, Donald Kueck, was a true desert solitaire. He had moved to the Mojave north of LA years ago to escape a marriage, becoming more and more isolated. His best friends were ravens and bobcats and even a rattlesnake that he kept at his front door as a kind of valet.

He was an avid reader, reading everything from Gail Sheehy's book about passages in life to Carlos Castaneda to search and seizure law, which he was well-versed in. Like a lot of people in the desert, he had a "No Trespassing" sign" at the turn down his driveway.

Yet behind it all, he had tried to reunite with his estranged daughter, and was successful to a degree, purchasing "loose gems" on the Home Shopping Channel as a kind of legacy.

He was able to reunite with his estranged son for a brief spell, and they ran around together in the desert, setting off rockets (Kueck was a self-taught rocket scientist and used to hobnob with engineers at Edwards Air Force Base).

But the reunion ultimately failed, and when his son overdosed at the age of 27 like his idol Kurt Cobain, Kueck went into a serious downward spiral, digging his own grave and attempting to contact his son through a time-travel contraption that he was building out of desert junk.

Throughout it all, he was consuming a variety of drugs, shooting at targets in the desert, and trying to get a cop who had once pulled him over on the road fired, sending letters to the sheriff's department and the FBI.

Then one day, that cop drove down his driveway, and Kueck literally went ballistic, taking out his rifle and blowing the cop's head off as he approached his door. (Was the snake rattling? Most likely.)

After he killed Steve Sorensen, he took off into the desert, kicking off a seven-day manhunt involving the FBI, DEA, Edwards Air Force Base, the LA County Sheriff's Department, hundreds of cops from nearby towns, and civilians on foot and horseback.

But there were also people who tried to help him out; leaving canned fruit on a plate out there somewhere as he made his way from water cache to cache that he had hidden away years ago, because you never know.

It all ended in a siege under a full moon, with Kueck surrounded by a ring of cops as a tank known as the Bear moved in while a homicide detective on a cellphone tried to convince him to surrender. It's a very dramatic conversation and I recount it in my book and some of it reminded me of a Tennessee Williams play.

Later it became clear to me that Kueck wanted to go out like Custer, that is, in a violent siege, in which he was defiant to the very end, the star of the show. In America, defiance is the coin of the realm, as we see all of the time nowadays, and we always have, but not so constantly. Kueck lived in a world of defiance and so do a lot of people.

It has become more and more apparent to me that when it comes to the problem of gun violence in this country, in addition to seeking an assault rifle ban and background checks, we need to ask what happens when personal pathology synchs up with our worship of personal rights?

This is what I'm looking at here and what I see playing out over and over again. Yes, "it's a free country and I can do what I want." But must we? And why is America frozen at the age of 12?

Q: How did you first learn about Donald Kueck and his murder of Stephen Sorensen?

A: It began as a siren call - literally. It was the summer of 2003 and I was visiting my partner at the time, photographer Mark Lamonica.

We were in his home in the Antelope Valley, which is the Mojave side of Los Angeles County, its strange cousin who lives upstairs, the part that receives little attention in the media mainly because it doesn't have beaches or Hollywood or Beverly Hills.

It was a hot August afternoon and suddenly there were sirens - not just the usual scream that you hear when a patrol car is racing somewhere, but one, then two, then dozens of sirens heading east, deeper into the nether reaches of the desert.

We turned on the TV, and there was the announcement: beloved deputy sheriff Stephen Sorensen had been found dead in the odd little burg called Llano, site of a failed utopian community whose ruins locals call "a socialist Stonehenge."

There was either an ambush or a shoot-out, and his killer was now at large, possibly hiding in the desert or on his way out of the area. Law enforcement was in hot pursuit, and the media ethers crackled with questions. Did he have hostages? Would he strike again? Was he heavily armed?

Soon locals picked up the beat in chat rooms across the region, offering to join the posse or cheering the outlaw on. After all, this is a land where many post no trespassing signs and they mean it. If a desperate fugitive were looking for refuge, they'd be ready.

On the other hand, some might help him. The Mojave is one of the most heavily armed regions in the country, a place where citizens are more than willing to step up on behalf of personal rights, in whatever way they see those rights shaking out at a given time.

As the afternoon unfolded, news choppers headed to the area. The questions became more heated and squad car after squad car continued screeching towards Llano.

Mark suggested that this was a story with my name on it. Yes, Joshua trees were involved, but I wasn't interested. I don't do "where's the fire" kind of reporting, and, when it comes to what I write, the kind of sirens on top of police vehicles are not what I respond to.

But over the next few days, it became clear that the man suspected of killing the sheriff had managed to elude a dragnet that was increasing hourly. This "person of interest" had been identified as Donald Kueck, a long-time resident of the Antelope Valley, a dedicated hermit who knew the desert better than most.

That immediately appealed to me; I'm a long-time desert wanderer myself, and whoever or whatever lives there - I get it, and I get them, and often enough I'm down with the program, especially if I can listen to George Thorogood or the Allman Brothers in some tavern along the way.

But there was more, and my interest only heightened. I soon learned that this hermit loved animals, and in fact his best friends were bobcats and ravens. Was he a Dr. Doolittle with an assault rifle? What was going on?

The more I looked into this story, the stranger and richer it got... the downed sheriff also loved animals and rescued them on his remote calls, often coming across abused creatures on his rounds, and, for instance, once picking up an abused pit bull at a meth lab and taking him home to his ark.

Frequently called to distant locations on his solitary beat, he was placing himself in harm's way perhaps more often than other cops (it might take half an hour at least for back-up to arrive), and in town he was deeply involved with citizens on a mission to help the helpless and clean up the desert, restoring it to a primeval state that was long-gone.

Was this guy a modern Wyatt Earp? I wondered. Who were the frontier sheriffs of the 21st century? And what was going on in the badlands an hour away from the Warner Brothers lot?

By then, I knew that I had already begun to tell this story, at least to myself; it had elements that appealed, including people whose voices were generally not heard and, of course, the desert itself, the terrain that shaped these latter-day pilgrims.

I called an editor at Rolling Stone, someone I had worked with before, and told him about this story. He was interested right away and assigned it and I wrote it. But I knew it needed to be a book; I couldn't fit it all into 8,000 words and so I headed on down the trail, and ultimately sold the book.

This deal came about during the last economic collapse, the Lehman Brothers thing, at a time when everything was falling apart, including the publishing world.

But it did happen - an editor named Carl Bromley at Nation Books, a long-time fan of my work, immediately understood what I was up to. He acquired Desert Reckoning and I spent a number of years working on it, and here we are, 10 years after it came out.

Q: How did you research the book, and did you learn anything you found especially surprising?

A: I did what I always do on my books - for starters, I spent time "on location," which I love to do. Place is a character in my work, and a driver of story, and so this was important, and not a problem at all, since I love the desert.

I also got to know some of the players in the story - friends of Kueck's and his son - who were a big help, though it does take years for people to open up. You just never know when it's going to happen.

For instance, there was a part of the story that I knew I didn't have and my book was running on three not four cylinders. But I had to turn it in by that point, and I did. Sure enough, just as my book was going to the printer, I received a call from a friend of Kueck's son with the missing piece of the puzzle.

So I actually got to call my publisher and say "Stop the presses!" And they did. It made all the difference.

Then there were some amazing things I found out during the hours I spent talking with cops.

For instance, one of the SWAT team members told me that during the final siege, they had fired a flash-bang into the shed where Kueck was making his last stand. The cop looked through the turret on the Bear and saw Kueck "bare-handing" the fusillade and tossing it aside.

Also, SWAT member Bruce Chase, now assistant sheriff of the LA County Sheriff’s Department, read a lot of Louis L'Amour when he was growing up. It was partly because of L'Amour's stories that he decided to join law enforcement.

As it happened, I too read L'Amour when I was growing up, and in fact one of his books, The Lonesome Gods, inspired an element of Desert Reckoning.

Additionally, Detective Mark Lillienfeld, on the phone with Kueck at the end, provided me with hours of tapes of those conversations, as mentioned above. At one point, Kueck - after seven days on the run and killing a cop - says "Don't tell my mom."

Lillienfeld was also on the phone with Kueck earlier in the week, when Kueck was calling his daughter in Riverside from somewhere in the desert.

Kueck apologizes for missing dinner and also - a good-looking guy who once resembled an Eddie Bauer model - asks how he looks, having been a fugitive for several days and his face now appearing on local television stations in "have you seen this man" coverage.

Later, I learned from Kueck's daughter that her father had been buying "loose gems" on the Home Shopping Channel as a legacy for her. The idea of the Home Shopping Channel serving as a vessel for accumulating treasure was amazing, especially since Kueck lived in the desert, site of rumored mines filled with glittering objects.

I should also add that during the course of my research, I met the then-current resident of Deputy Sorensen's house, a large compound in the Mojave. She gave me a tour, and the house had come with animals that Steve had rescued - pit bulls and even a horse. It was like an Ark, and so was Kueck's place in its own strange way.

And then she unlocked his office door and let me in; no one had been there since he was killed. I spent a little while there, taking note of his hotplate and coffee cups. And then there it was - a coffee maker and it still had a filter in it, as I recall.

A cop and his coffee, I thought, as I sat in his chair and stared out at a butte, the same one that Kueck looked at from his broken-down Barcalounger outside his trailer as he fed the ravens and squirrels every morning. That moment in Steve's office opened up a pathway for me into the story.

Perhaps the wildest thing I learned was that cops were staging at a convent that was close to where Kueck was hiding near the end. It was the only place which had enough space around it for a chopper to land.

The nuns were cooking and praying for the SWAT team as the manhunt was underway, with some members sleeping on the floor there and then running in and out in pursuit. The nuns had known Deputy Sorensen, the cop who was killed, and like others in the community, felt the loss acutely.

In my book, I write about two cloistered orders coming together - cops and Benedictine nuns - and an especially poignant and unexpected thing that happened because of that. You gotta read my book to find out what that was. You will be very surprised!

Q: The Kirkus Review of the book says it has "aspirations that suggest influences including Joan Didion, Cormac McCarthy and James Ellroy." Did those writers serve as influences for you?

A: These are all great writers, of course, and anyone who has been breathing the literary ethers for the last 50 years, especially in California, has of course been influenced by Joan Didion, one way or another.

People often compare my work to hers, and I take that as a tribute. In general, it's because I write about the desert and people on the edge, but beyond that, there is a world of difference. I'm directly engaged with my characters, and she is not.

That's not a criticism; you could say that my writing is "hot," meaning heated, and hers is disengaged; she is not "with" her characters, she is next to them or near them, or even across the street. So this Kirkus observation is not really accurate when it comes to Didion.

Ellroy has never been an influence, but again, I've heard that before, I guess because of the "noir" aspect. As for Cormac McCarthy, yes, definitely, he is a long-time influence, along with many others, including Melville, Willa Cather, Barry Lopez, Rick Bass, Guns 'N Roses, Jimi Hendrix, Alice Coltrane.

What's on my mind as I'm writing more often than other books or writing styles is music and its rhythms. Desert Reckoning in fact opens with lyrics from "Renegade," the Styx song, and it's the backbeat of this story.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I'm working with Carl Bromley again, now at Melville House. He acquired my book American Confidential, which is about Lee Harvey Oswald, his mother, gun violence, and how we raise our sons.

So it further explores what's in Desert Reckoning, and of course with these recent mass shootings, is very relevant, and I'm writing it as we speak.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: I really hope that we as a country can take a deep look at our obsession with personal rights. I carry the Constitution in my purse and I take our founding documents very seriously, including the Bill of Rights, as do we all. In no other country does the word "freedom" appear in so many origin stories.

But unless we start talking about why we must do whatever we want whenever we feel like it, no matter what the cost, because it's a right, then we are steering clear of one of the most important conversation we can have as Americans. Who are we and what's so terrible about walking away from a bar fight?

--Interview with Deborah Kalb. Here's a previous Q&A with Deanne Stillman.

No comments:

Post a Comment