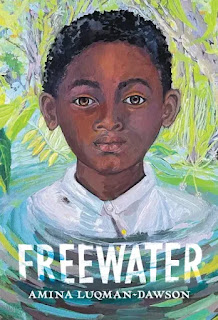

Amina Luqman-Dawson is the author of Freewater, a new historical novel for older kids. She also has written the book Images of America: African Americans of Petersburg. She lives in Arlington, Virginia.

Q: What inspired you to write Freewater, and how did you create your character Homer?

A: The wonderful history behind Freewater was my first inspiration. I first learned about maroons in the Americas while in college. I was utterly fascinated by the enslaved people who managed to escape and live free and clandestinely in the wildness.

I was also inspired by my son. My husband and I were both wanting to find a new and innovative way to discuss the nation’s history of slavery with him. I wanted to find a way to do it on his terms, through a complex story of adventure and intrigue. I wanted that for all children.

From my earliest draft, Homer has always been my protagonist. However, it took time and several drafts to make him fully realized. He was my first exercise in finding the voice of an enslaved child.

At first, I felt quite shy about capturing that voice. But the wonderful thing is that once I did that work, I found a multitude of other characters and learned over and over again, that enslavement isn’t one story, it’s the cacophony of personalities, experiences and voices. That’s how many of my other characters were born.

Q: The Kirkus Review of the novel says, in part, “Set in a fictional community but based on real stories of those who fled slavery and lived secretly in Southern swamps, this is detailed and well-researched historical fiction.” How did you research the novel, and did you find anything that especially surprised you?

A: My research was multilayered-like peeling an onion. I began with maroons throughout the Americas—Jamaica, Surinam, Brazil and more. That text is quite rich. Some maroon communities in those countries were so strong their descendants still remain on those lands. They had a number of clever and innovative means of survival that helped enrich Freewater.

Still, my research continued, as I was hoping to find evidence of maroons in the United States. That’s more of a challenge.

I was fortunate to find the work of historian Sylviane Diouf. Her book, Slavery’s Exiles: The Story of the American Maroons, was released during my research hunt. It’s a comprehensive look at maroons in the forests, swamps and mountains of the southern United States. It’s there that I learned of the Great Dismal Swamp.

I was attracted to the Great Dismal because it was known to be a refuge for African Americans from the 1700s until the Civil War. I was captivated by reports of the maroons who lived there. On a few occasions they discussed children among them. Children! I was enchanted and felt so fortunate that The Great Dismal is located in Virginia, where I reside.

Anyone who knows about the Great Dismal knows about the work of Dr. Daniel Sayers. He’s an archaeologist who has been exploring the elevated lands of The Great Dismal in search of evidence of maroon and indigenous life. I met with him at American University and got goosebumps as he discussed his work.

Then I went to visit the Great Dismal. That was a fascinating and overwhelming trip. Of course, along the way I read books, research papers, and articles on the Great Dismal--from Dr. Sayers’ archaeological book, to the Autobiography of Moses Grandy, who was enslaved and spent years working in the Great Dismal, and much more.

It was a wonderful adventure in research. I learned a great deal and yet, I was also saddened that there weren’t more means to hear the voices of maroons themselves. It’s a terrible loss that’s mirrored in many aspects of African American history.

That we need an archaeologist to help tell the story of the maroons of the Great Dismal is quite telling. We are literally digging in the dirt to find small shreds of evidence. The precious texts we do have are invaluable; however, they aren’t nearly enough to capture the full breadth of the experience. I feel a great duty to fill that void.

Q: Did you know how the novel would end before you started writing it, or did you make many changes along the way?

A: My novel ending was clear to me by maybe my third draft. I could feel the ending, the task was figuring out how to get there.

At one point, as I worked on character point of view, I did change the ending. However, it didn’t take long for me to miss what I’d originally envisioned so I reverted back to it once again in subsequent drafts. I did end up tweaking the ending quite a bit, but the basic form of it stayed the same.

Q: What do you hope readers take away from the story?

A: So much. So very much. Throughout my childhood, the nation’s story of enslavement was difficult for me to face. I think that’s true of many Americans. The topic is rife with pain and suffering. All of that is true must be respected.

However, there is also empowerment, love and even beauty to be found in the voices of those who were enslaved. Freewater is a new means of getting to those voices. I want readers to complete this book and feel connected to these young characters. I want them to feel like old friends you’d want to visit.

Once you have that feeling, you’re in touch with the true humanity of the enslaved people behind it. That’s a good place to begin a new discussion of this nation’s hard old history.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I do have another project in the works. I don’t have much detail to share about it at this time.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: Freewater was written with children in mind; however, it’s not just a children’s book. There is much that can and should be gained from adults reading it as well. We all need a space to connect with this history—and a thrilling, heart-warming adventure tale is great place to start.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment