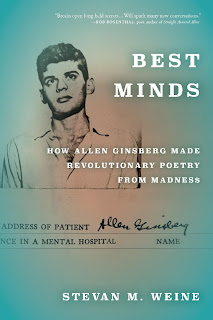

Stevan M. Weine is the author of the new book Best Minds: How Allen Ginsberg Made Revolutionary Poetry from Madness. Weine's other books include When History is a Nightmare. He is Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Illinois College of Medicine.

Q: What inspired you to write Best Minds, and how would you describe your relationship with the late poet Allen Ginsberg?

A: I have long been fascinated by how people make meaning and art from mental suffering. When I first read “Howl” and “Kaddish” as a teenager, I was immediately taken by Ginsberg, who was fully engaged in this kind of work.

I read everything I could and learned a little more about his mother, Naomi, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia and spent many years in psychiatric hospitals. I learned that Ginsberg himself was involuntarily hospitalized for eight months in his early 20s not long after he had visions of God inspired by William Blake.

That got me wondering, what did Ginsberg really think of psychiatry and how it approached madness in comparison with literature? So in 1986 I wrote Ginsberg a letter, he answered, we met and started talking. He let me interview him several times, and gave me access to his archives, his psychiatric records, and those of his mother.

When I was only 24, he handed me an incredible opportunity to tell a story which to this day has not been fully told. He also became a mentor to me as a young psychiatrist, having me read William James and Antonin Artaud, for example, and then discussing them with me.

Q: How do you think Ginsberg addressed his mental health issues, both in his life and in his writing?

A: When Ginsberg was hospitalized at the New York State Psychiatric Institute in 1949, he had formal psychiatric treatment in the form of psychotherapy. In Best Minds, I discuss this in great detail, based on the progress notes from the medical records and Allen’s recollections.

Later when living in San Francisco, he had psychotherapy again which helped him accept being gay and a poet. In his 50s, he again entered into therapy when coping with his partner, Peter Orlovsky’s, drug habit and manic episodes. All of these treatments were helpful to Ginsberg.

But let’s not overlook the work Ginsberg did as an artist every day of his life, journaling, corresponding, studying literature, writing poetry, documenting and examining his inner life and daily experiences, those around him, and society at large.

I am amazed at the courage, commitment, discipline, and creativity which he brought to his suffering and that of others. As Patti Smith explained to me, he did the work of an artist.

Q: How would you describe the dynamic between Ginsberg and his mother, Naomi?

A: Loving but also ambivalent and complicated. As a child and young adult, Allen was her caregiver and protector, but unfortunately, also at times a victim of her delusional behavior. For years he tried his best to save her from her illness and from the hospitals. Some big decisions fell upon him alone when he was still young.

Despite all her suffering, Naomi still saw herself as a mother and tried her best to give her love to her sons, even from a locked psychiatric ward.

Q: How was the book's title chosen, and what does it signify for you?

A: “Best Minds” comes from the first line of “Howl”: “I’ve seen the best minds

of my generation destroyed by madness.” As I explain in Chapter 6, this line is

written from the perspective of a witness and is laced with ambivalence. Were

they or are they the best minds? Did madness make or break them?

The rest of the title, “How Allen Ginsberg Made Revolutionary Poetry from Madness,” is really what this book aims to achieve. Again, how does a young person confronted with horrific suffering and also immersed in literature manage to turn it into remarkable art that impacted many lives.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I work in global mental health, which takes me to Central Asia and other destinations. We build interventions to support people who are suffering from mental health problems in the context of social adversity, and do not have access to mental health resources.

I am also finishing some small pieces that didn’t make their way into this book. One piece on Ginsberg and Bob Dylan as witnesses to social injustice. Another on Jack Kerouac and Ginsberg’s friendship around the time of Allen’s visions. Another on what would Ginsberg say we should do to help persons with serious mental illness on the street.

The most important one to me is on Naomi Ginsberg, which is focused more on her, and less on Allen. Naomi, like so many others, disappeared into the psychiatric hospital, and was silenced. Fortunately, in her case there is some documentation, which allows us to get to know her and her struggle.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: I can’t overemphasize how excited I am to share this book with readers. I’ve lived with this project for more than half my life.

In that time it has developed in ways that I hope will connect with multiple audiences. Those who know a lot about Ginsberg and those who only heard of “Howl” or “Kaddish.” Those focused on poetry and the Beats, and those interested in trauma, madness, and the history of psychiatry. Allen Ginsberg contained multitudes.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment