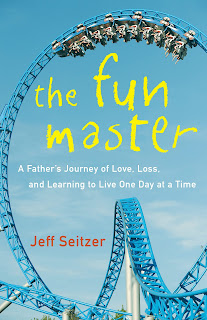

Jeff Seitzer is the author of the new memoir The Fun Master: A Father's Journey of Love, Loss, and Learning to Live One Day at a Time. It focuses on his late son, Ethan. Seitzer lives in Chicago.

Q: Why did you decide to write The Fun Master?

A: I was all thumbs when I first took over the care of our infant son Ethan in fragile health. Fortunately, my mother-in-law Aleta came to help, and despite the intense pressures of the situation we shared a lot of laughs about my high learning curve.

She assured me that everyone struggles as a parent and suggested that I keep a journal with a view to publishing stories about my experiences one day.

When our son Ethan was still very young, however, I decided I wouldn't publish anything, because he did not like to be the center of attention. As he put it, “Some people like to be the main character. But I don’t.”

I still continued to make journal entries, so that when he was older I could remember the details of our time together. I ended up with over 4,000 pages of notes.

Then the unthinkable happened; Ethan drowned just shy of his 10th birthday. While we were sinking together, I was certain that we were both going to die. My last thought before blacking out was “I will not be able to tell his story.”

According to witnesses, I was under water for several minutes. When I finally surfaced and was pulled to shore, my hands and feet were blue from oxygen deprivation. I can't account for my survival. But I do believe that I was somehow spared to write this book.

I also wrote it, however, because the story itself has an important human dimension. It is often said that a good parent can make a big difference in the life of a child in need. This story shows that a special kid, in particular a child with special needs, can make a big difference in the life of an adult, especially one like me with special needs.

Q: I am so very sorry about the loss of your son…

What impact did it have on you to write the book, which deals with this heartbreaking loss?

A: Writing about Ethan's short life was like a form of channeling. I wasn't just composing a narrative about our time together; I was re-experiencing it. I could hear his voice, enjoy his throaty laugh, and even feel his touch. He came to life again for me on the pages, which helped me find a way to go on living without him when I wasn't writing.

The sad fact remained, however, that I couldn't tell his story, and mine too, without addressing his death. That meant leaving the comfort of the eternal present created in the lines of the memoir. Even five years after his death, it was still too traumatic for me to write about his drowning.

So, I composed a neo-Greek tragedy as a final chapter instead. Based loosely on Euripides's Hippolytus, it attributed Ethan's drowning to jealous gods conniving against one another. It was an effective distancing technique, for me at any rate. However, honest readers were compelled to say, “But people will want to know what really happened.”

I finally resigned myself to writing about what really happened. The downside of channeling became immediately evident.

Writing about his drowning brought me back to the beach. Struggling to stay above the surface; hopelessly sinking together; watching his lifeless body being pulled from the water; seeing his beautiful face, his entire body in fact, turned blue like my hands and feet; in the ambulance with my wife praying for a miracle.

I couldn't think of that day without sobbing. Writing about the drowning was not just traumatic; it was also agonizingly slow. A few words a week, with some weeks nothing at all. Eventually, though, I was able to get it all down on paper.

Now, 12 years later, I can read my account of his drowning without collapsing onto the floor in tears. This is not to say that I am "over it." On the contrary. Grief for me is like a disability, something with which I will always have to contend.

Writing the book, however, has helped me adapt to my disability, enabling me to function well on an everyday level. In that sense, completing the story was therapeutic, and I am grateful for that.

Q: How would you describe Ethan’s legacy?

A: Ethan changed the vibrational level of all those around him. He had the instinctive ability to identify a way to connect with people, even with those who had not been kind to him before.

This was not because he was naive or overly eager to be liked. It was because, again instinctively, he wanted each moment with others to be a positive experience. Focusing his gaze on the things they shared brought the best out in people and encouraged them to accentuate the positive in that moment as well.

My instincts are different. Recent psychological and neuroscientific studies show that negative experiences imprint especially powerfully on humans. I knew this long before I taught the philosophy of happiness, which addresses such predispositions.

A childhood bout with encephalitis left me hyperactive, moody, anxious, and with a flash temper, among other problems. Negative past experiences have always inclined me to expect the worst from people and often to assume a defensive posture when dealing with others. Negative experiences also encourage in me a feeling of disappointment in life generally.

Reminding myself of Ethan's positive outlook helps me break this tendency toward negativity, or at least moderate it. He made so much of his short life by expecting little of people, which, interestingly, enabled him to get more from each experience with them than one might have expected.

And he never bemoaned his fate. Life had thrown him many curve balls, as it has me, and yet he never seemed resentful or bitter, for these would distract him from enjoying each moment.

Emulating his approach to life takes quite a bit of conscious effort, and I have had mixed results. But I have come to believe that we are put on earth to learn. Each person in our lives have something to teach us. This was Ethan's lesson to me, and I am determined to make full use of it.

Q: What do you hope readers take away from the book?

A: A feeling of hopefulness. The Fun Master is an ode to the wisdom of children like Ethan with special needs. Though life has been hard on them in many respects, they have no time for anger, self-pity, or exclusiveness.

Their persistent joyfulness amidst pain and suffering demonstrates how we all can learn to live differently. Such kids are our great teachers. We should look to them for a way out of the darkness gathering around us now.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I am writing a nonfiction book for a general audience entitled Living Philosophically, Poetically, and Politically. The basic idea is that a spiritual life guided by philosophy and science can make you happy as well as a better person.

Sacred texts should be viewed as potential sources of wisdom, not as sets of divine commands that one must blindly follow. Religious beliefs, in other words, should be treated as ideas for effective living that can be examined as scientific hypotheses.

Using all the modern tools of the natural and social sciences as well as philosophy, one considers the consequences of such ideas for an individual's life and for the welfare of society.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: Writing has brought me together with so many wonderful people. I would love to hear from you. Please feel free to email me at jeff.seitzer5120@gmail.com. Also consider visiting my website, www.jeffreyseitzer.com, to sign up for my newsletter.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment