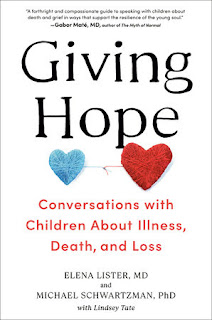

Elena Lister and Michael Schwartzman are the authors of the new book Giving Hope: Conversations with Children About Illness, Death, and Loss. Lister is a psychiatrist and grief specialist, and Schwartzman is a psychologist and psychoanalyst.

Q: You bring personal and professional experiences to the topic of speaking with kids about death--what brought the two of you together to write this book?

A: We each have been deeply affected by the illness and loss of people dear to us--as we believe is true for most of us humans. We’ll each talk about the personal part of what drew us to writing about dealing with dying and death and then how we came to work together on it.

Dr. Lister: My younger daughter Liza, died of leukemia when she was 6 years old. Through the two years of her illness and then death, my family and I experienced the connecting and healing power of honest and heartful communication about what was so deeply painful for all of us.

Working with my daughters’ school, I saw that when even young children learn about death and loss with compassion and empathy, it is possible for resilience and hope to develop. It was a major turning point in my career, not just my life.

After years with a therapy practice helping people face all life challenges, I began to devote a significant part of my work to helping parents and children, schools and communities cope with illness and loss--bringing the agony of the death of my daughter, and all that I learned in the process of experiencing it, to some good by helping others not feel emotionally alone facing what feels unbearable.

I also began to teach at medical centers across the country about how to talk with children and families confronting illness and dying since I saw how important that was in the care of families.

Dr. Schwartzman: I’ve always been drawn to things that scare me and particularly moved by people who confronted and survived emotional pain.

Through my career I have worked with people facing crushing emotional experiences such as illness and loss and seen how talking through feelings and thoughts, bringing unconscious emotions and forgotten memories to the surface helped people find relief.

I could see that parents who could put their own concerns aside for a moment to attend to their children could be healers for their struggling young ones. I brought that understanding to being the consulting psychologist at two schools weathering all sorts of tragedies and crises large and small.

I had had extensive experience working with one particular school when the mother of a young student there was diagnosed with a terminal disease. I had established a psychologically-attuned and responsive approach to meeting the emotional needs of children that encouraged engagement with parents and talking openly within their families.

To join me in bringing that to facing this imminent loss, the school brought in Dr. Lister because of her immense experience helping families and communities facing illness and death.

We worked side by side to help parents understand their own reactions, to guide them in talking honestly with their children about what was happening and to support teachers coping with their own feelings of loss as well as be prepared to speak with the children about illness and death.

When this parent died, we continued working together with the students and to help the community grieve, creating ways to honor and remember her and providing further gatherings for parents to talk about what they were feeling and how things were with their children.

Through that experience many years ago, we found that we both held a strong conviction about the importance of conversation with children as a path toward deepening connection with parents and other caretakers when facing life’s challenges such as illness and loss. And we became friends as well based on shared values as well as mutual respect and enjoyment.

Dr. Lister: When I found in my work that caretakers longed for a resource they could read and return to time and again when taking care of children facing loss, I decided to write this book and asked Dr. Schwartzman to do so with me.

The process of writing the book demonstrated the very concept we so deeply believe in--that through conversation comes growth, understanding, and connection. Our collaboration has been a challenge and a joy--each of us learning from the other as we propel each other forward creatively.

Q: Dr. Lister, I’m so sorry about the loss of your daughter…

To you both, I wondered, how was the book’s title chosen, and what does it signify for you?

A: As we have found in our work, no one wants to talk about death. However, death is an inevitable part of life, so talking about death is an inevitable part of parenting.

Often people feel they should not talk about death because it will upset children. But children think about and are exposed to death anyway, and it is far worse if they have to sort that out alone.

We wanted to help caretakers generate conversations with children that support them and open up room for feelings and thoughts that are hard to manage. Faced together, the pain is easier to carry.

We believe that when we confront difficult things together, we build deep connections with each other and out of that comes strength--you know you can do it--and resilience--you know you can endure it. Hope for the future grows within a child as they feel belief in themselves facing any hard things to come since they have faced difficult times before.

Hence our title: we believe that through open honest compassionate conversations, caretakers give children the gift of hope. Much as we might wish to, we cannot change the reality of death and loss but connection and hope do change and ease how we face them.

Q: Can you say more about the impact parents and other adults can have in helping children process loss?

A: Parental and adult help is crucial for children who must cope with loss. Since the first steps in processing any loss involve allowing oneself to realize that this is what you are up against and learning how to carry yourself while in emotional pain, it is important for parents to model this for their children.

Children need to learn how to identify and name their feelings, to accept and express what it feels like to live in this space. They learn to do this by observing their parents and through the direct teaching and learning that occurs in conversations no one really wants to have. By modeling and teaching, parents can ease their child's experience within the comfort of togetherness.

Conversations, between each other and, then, also within oneself can make hard feelings more bearable. The inevitable changes that come with illness, death, and loss can bring transformations that yield a renewed sense of being, rather than only a sense of diminishment.

Q: What are some of the most important things you hope readers take away from the book?

A: We envision this book to be a companion to anyone deeply absorbed in the difficult experience of helping a child through a significant loss. Caretakers in this situation can feel very distressed and uncomfortable themselves.

Although this may seem inevitable, we have found through our clinical work and through the difficult conversations we ourselves have experienced that one does not have to be wary or afraid. We have found that making conversations about difficult experiences is key to processing those experiences in a healthy way.

By understanding your own experiences of loss, you can better separate your experience from your child’s, while at the same time using your understanding and experience to guide your child in identifying and managing their own upset.

Grounding yourself first by addressing your own emotions enables you to focus in on your child's intense feelings, apart from your own, and support their expression of emotions and their efforts at settling themselves.

We know that on their own, children pick up on what is happening around them. They also tend to be very tuned in to their parent's emotions. So, if you have settled yourself, they will sense this, too, and it can be very reassuring to them.

It is important that a child feels that there is support for them. Their resilience develops, not from avoiding hard feelings, but from experiencing them, naming them, and communicating them. Your child’s strength comes from going through all of this in partnership with you, entwining the pain suffered with the togetherness shared.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: When we began our project, it was well before the Covid pandemic began. The last few years with that and more--such as war, gun violence, and climate catastrophes all part of a constant 24-hour news cycle--have brought a deep awareness of illness and death into the lives of our children. They are growing up in a soup of mortality.

We turn our focus now to helping people face more specifically these ever-evolving crises in our world and within their lives. We respond to how these impact people and want to continue to be a resource for caretakers and children as they face each new thing yet to come.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: Every day, we are moved by the privilege of listening to the stories of how people live their lives. Again and again, we have found how important it is to face up to life's inevitable hardships, but also how equally important it is to balance this with finding joy in the here and now.

Many people have told us they do not know how we do this work. The answer is that we are energized by the resilience and hope that springs from the hard work we share with parents and their children.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment