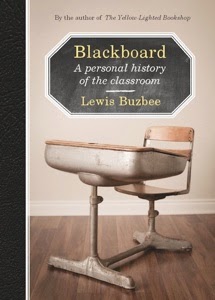

Lewis Buzbee is the author of the new book Blackboard: A Personal History of the Classroom. He has written many other books, including three for younger readers, and he teaches creative writing to adults. He lives in San Francisco.

Q:

You write that "school saved my life" after the death of your father

when you were in junior high school. What role did your teachers play in

helping you get through that difficult time?

A:

My teachers—and my schools!—kept me busy, that simple. My teachers engaged me in subjects they found

I was interested in, they prompted me to follow my own interests outside of

school, they offered me a glimpse of my future and pointed me in the right

direction.

So,

they put books in my hands—I was a reluctant reader then—they knew would touch

me, and encouraged me in writing my own short stories, then they read them on

their own time and talked to me about them. They cast me in plays and gave me

someplace to be every day, taught me about the hard work of making something

with a big group of people.

They

found time for me. I spent hours in their classrooms after school, either

talking about school tasks, or just talking. And during these times, they took

me seriously, as a person. Most importantly, they came to me, found me, made

these offers on their own. They saw a kid in trouble and reached out to help.

And

they had the time to offer me, had the space in the classroom to be able to see

how I was failing.

When,

as is often the case in today’s public schools, a teacher has 40 kids a class, five

classes a day, that time and space is lost.

It’s too easy to remain invisible in such a classroom.

Q:

In the book, you compare your own experiences in school with those of your

daughter. What would you say are the biggest similarities and differences?

A:

My daughter has been fortunate enough to attend private schools. This is a

choice my wife and I made, and we’ve made her happen by chasing financial aid,

being diligent, doing our homework.

And

what I see in today’s private schools—Maddy’s a junior in high school now—is

similar to what I saw in my public schools from 1962 to 1975. Art and music

instruction. Bountiful supplies. Clean and welcoming classrooms. Teachers who

are well paid and well respected. Manageable class sizes. An emphasis on the

whole child, the big picture.

When

I visit public school classrooms as a writer of books for younger readers, I

find terrific teachers, dedicated teachers, but teachers who are overwhelmed by

both the magnitude of their task and a bureaucracy that’s onerous and

creaky.

My

education was aimed, always, at the bigger picture, the world that waited

beyond the classroom. What I see in public schools today is an education system

that’s aimed at tests and scores.

Q:

You describe yourself as an "average student." How would you define

"average"?

A:

I’m not trying to be falsely humble when I say I was an “average” student, but

I was. I was no whiz at anything in particular. Oh, I was smart enough to get

by, was affable and polite, could talk my way through and around things. But I

was no gifted student, not even close.

I

mean “average” in the best way. Average in that I came from a comfortable

working class home, a supportive and stable home. But we were not a college-bound

family in the least. Still, my teachers and my schools offered me a spark, a

new way of seeing the world.

I’m

still average, of course, it’s just that I was blessed to have teachers who

showed me that the world was bigger than my own backyard. They made me curious

about that world, and sometimes, that’s all you have to do for a child.

Q:

As a teacher yourself, how do you draw on your experiences with your own

teachers in dealing with your students?

A:

Let me be clear, I have it easy as a teacher. For 20 years I’ve taught writing

to adults, in extension courses and in an MFA program, and that’s a pretty

cushy gig.

First

off, I have students who elect to be there, and that’s an advantage right off. I

read manuscripts, and works from the published literature, and we all talk

about them. Great fun. Nothing at all like the hard, hard work that K through 12

teachers do, nothing at all. That’s real work.

But

what I try to bring to my classrooms is the big lesson my teachers taught me:

It’s not what we learn that’s most important, but how we learn.

I’m

not interested, necessarily, in passing on a body of knowledge—my body of

knowledge--but rather am more keen on getting my students to teach themselves. Teach

themselves how to read, teach themselves how to write, teach themselves how to

see the world. If I can impart the sense that education is a long, self-driven

process, then I’ll consider myself a successful teacher.

Q:

What are you working on now?

A:

I’ve just finished my first true young adult novel—my earlier books were middle

grade. It’s called Garbage Hill, and it’s about a one-day music festival, where

seven kids from different worlds meet up and end up going home together. It’s

not about the music business, but rather how music is so important to us when

we’re teenagers.

The

great joy in writing this book has been going to shows and festivals with my

daughter, and hearing gobs of fantastic new music. And of course, being able to

loosen the strictures a little and go all sex, drugs, and rock‘n’roll.

And

I’ve just started a new novel for much younger readers, 8 through 10 years old.

It’s called Duh! and is about a boy who, while smart, is a little slow in

putting things together. He discovers that his slowness is actually his great

strength, however. This is proving super fun to work on, being a 5th grader

again. Yes, it’s somewhat autobiographical.

Q:

Anything else we should know?

A:

What I most want from Blackboard is to be provocative, that is, to provoke the

reader's own memories of school. I put no prize on my own memories--I was,

clearly, average.

It

was the classroom that mattered to me when I was writing this book. What I came

to understand about school, essentially, was that this is where children spend

their lives. I hope I can remind us all of that fact, that school is where it

happens. Not in legislatures or board meetings or PTA meetings. School is about

the experience of being there, not the expectations society holds out for its

"results."

If

we can remember this, truly and viscerally understand this reality, then I

think we'll design, and fund, better schools, and equip those schools with

enough dedicated, and respected, teachers, all of which will make a real

difference in the futures of our children. And of course, make a real

difference in the future of our world.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment