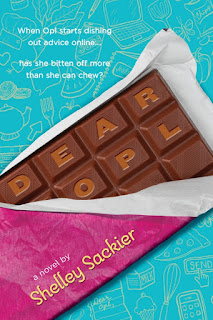

Shelley Sackier is the author of the new young adult fantasy novel The Antidote. She also has written The Freemason's Daughter and Dear Opl. She lives in Virginia's Blue Ridge mountains.

Q: How did you create the world you write about in The

Antidote?

A: Sometimes I feel I spend more time on researching my

books than I do actually penning the story. But this is where I feel most

creatively inspired. I seek out books, experts, and places within the world

that will formulate a setting which is the ground where I plant my narrative

seeds.

It feels rather effortless to choose a canvas where the

sphere of the story will unfold, as long as I pursue those old textbooks, or

hedge witches, or biologists, or crumbling castles and steep myself within

them. The world is rich with hidden realms waiting to be discovered. I love the

sleuthy part of that kind of work.

Q: Did you know how the book would end before you started

writing it, or did you make many changes along the way?

A: In the somewhat unexplainable world of writers, we’ve got

pantsers and plotters. Writers who are pantsers are those that typically write by

the seat of their pants—as in, you develop the story as you go along and trust

the process and whatever muse shows up to shine on light on the pathway forward.

Plotters are authors who typically and diligently outline

the narrative arc before they fill in the gaps of how they’re getting from

point A to point B. They bullet point every chapter and make sure they nail the

ending before fleshing out all the itty bitty details.

I am a “pantser.” Stephen King described the process

beautifully in that it’s a bit like being an archeologist, where you find a shard

of bone sticking up out of the earth, and then patiently, and meticulously, you

use a fine brush to dust away the sand and dirt, slowly revealing the skeleton

of a story—large, small, frightening, awe-inspiring, rare, or middling and

unexceptional—you sit and see what your labors reveal.

Q: What do you hope readers take away from the story?

A: Although one of my main messages—in each one of my

books—is unwavering advice to never enshroud yourself in someone else’s skin,

as in “wear who you are proudly and confidently,” I also feel somewhat

compelled to encourage kids to challenge the status quo of authority.

Not in a blindly arrogant way, but with diligently collected

and persuasive data. If you are unhappy with the rules, challenge them and

change them. Not necessarily to benefit the few, but to collectively push our

society forward with fresh ideas, compassion, acceptance, tolerance, and

wisdom.

Young adults are often cast aside as being argumentative for

the sake of being blind with belligerence stemming from hormones, but they are

also capable of being highly credible and convincing. I want them to realize

that power, and harness it for good—for their generation and the ones before

and after them.

Q: You've said that for years you were too embarrassed and

wary to believe your relatives' tales about the magic passed down through your

family to you. What made you change your mind?

A: Mostly other people. People whose education, philosophy,

mindset, and life experience I held in high esteem. Their words to me were,

“How can you talk it but not walk it?” In essence, I have to practice what I

preach.

My books and school talks are filled with examples of other

people living successful and exciting lives as outliers. They did not follow

the crowd. They listened to the core voice inside of them that begged not to be

squelched—the one that said, “Stop hiding.”

It felt like the right, albeit uncomfortable, thing to do.

I certainly don’t have to admit to any title my clansmen and

women embrace, but I do finally feel at ease admitting to being one of the

clan. Basically (and humorously), I got comfortable with being uncomfortable.

Q: How do you identify with your character Fee?

A: Like The Antidote’s 16-year-old heroine, Fee, an

undiscovered witch disguised as a healer learning to distill plant life as it

applies to the creation of medicines within her flora homeopathica textbooks, I

have studied the art of distillation for 25 years, as it applies to the

creation of a different kind of potion—whisky.

I began studying the science in earnest, apprenticing at a

distillery in Scotland. I occasionally intern elsewhere but still see each of

my mentors as wizards of the most magical sort. Although, it’s agreed that

science explains most of the “magic” away, there are elements that remain

thankfully, and artfully, not fully revealed.

Fee and I struggle with similar difficulties: I walk a line

between my work writing fantasy, and my tenuous pupilage in engineering and

science. I create two things—one needing only a strong believability factor,

and the other, a step by step proof of accomplishment, impervious to doubt.

I resist the undisputable explanations of science because it

strips away the desperate need for magic I maintain. But one loses credibility

with others if one blindly and indulgently replaces fiction for fact.

Fee’s conflicts are mirrored but flipped. In her world,

sorcery is legitimate and deadly if discovered. Dismissing her knack with

nature—allowing life to flourish within her hand—or refuting her ability to tap

into the magnetic essence of life, completes our shared disharmonious circle.

But in her case, Fee’s conviction in her self-created deception tears away at

the fabric of credibility to trust oneself.

Q: Which authors do you particularly admire?

A: My main source of inspiration are people wholly unrelated

to the publishing world of YA books. I am steeped in the writings and thought

process of philosophers, mystics, social scientists, and economists. I love

economists.

Authors like Seth Godin, Brené Brown, Pema Chodron, Angela

Duckworth, Shankar Vedantam, and Stephen Dubner.

These people help me see the world in its most promising and

starkly truthful ways. It’s from here that my stories spring forth. How humans

survive and thrive within our wishfully ideal ways and also the truest

circumstances of today’s challenges.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment