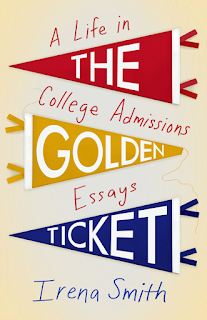

Irena Smith is the author of the new memoir The Golden Ticket: A Life in College Admissions Essays. A college admissions expert, she was born in the former Soviet Union and emigrated to the United States as a child. She's based in Palo Alto, California.

Q: Why did you decide to write The Golden Ticket, and over how long a period did you write the book?

A: I wrote The Golden Ticket because I wanted to address the disconnect—chasm, really— between my professional life and my home life.

At work, I counseled students on how to tell their best story and to gain admission to some of the most selective colleges in the world; at home, my husband and I were struggling to raise three children with developmental delays, depression, anxiety, and learning differences.

In Palo Alto, where we live, everyone talks about getting into college (and not just any college, but the good kind), which doesn’t leave much room for conversations about kids who aren’t ready for college, or don’t want to go, or might be struggling with challenges that go beyond deciding which top 20 school they’ll apply to.

In telling both parts of my story, I wanted to provide a larger context for what Frank Bruni calls “Yale or jail” thinking about success—and to open a broader conversation about what it means to be successful or to lead a meaningful life. Not every success story ends with the name of a prestigious college on the back of a late-model luxury car.

I began writing some of the essays that appear in the book when my oldest son was four years old (he’s now 28), so I feel like I’ve been writing it for most of my adult life.

And honestly, I don’t think I could have finished it any earlier, because it took me that long to understand that while the specific story I wanted to tell—raising children who didn’t check the conventional boxes for success in the shadow of Stanford University and everything it stands for—was actually part of a far older, larger narrative.

At heart, the story is about parents, children, and the weight of expectations—a story that’s at least as old as the book of Genesis.

Q: How was the book's title chosen, and what does it signify for you?

A: I wrestled with the title for over a year, trying to sort out how to strike the right balance between optimism and cynicism, aspiration and reality. (I should note here that I am truly terrible at titles, so apart from my own inadequate attempts, I had suggestions from my agent, my editor, my publisher, and various friends and family members.)

My husband was actually the one who came up with “The Golden Ticket”—which I initially rejected because it sounded like the name of a children’s book—but the more I thought about it, the more it made sense.

In Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, the golden tickets are such a coveted commodity that people go to ridiculous lengths to secure one (in ways that are not dissimilar from the ridiculous lengths parents go to try to secure acceptances to prestigious colleges for their children).

But it turns out that having a golden ticket—at least for four of the five children who enter the chocolate factory—is not so great (okay, it’s really awful—I mean, we’re talking major physical and emotional trauma).

That reversal really resonated with me. So much of my book is about expectations—the expectations my immigrant parents had for me, the expectations my husband and I had for our own children, the expectations my students and their parents bring to our work together—and it is also, in equal measure, about ways in which those expectations lead to unexpected, and sometimes unwelcome, consequences.

Point being, I suppose, to check your expectations at the door, or at the very least, be careful what you wish for.

Q: On your website, you write of the book, “I don’t always appear at my best, but then again, I’m not trying to get into college; instead, I respond to college application essay prompts as honestly as I can.” Can you say more about that?

A: I have SO much to say about that. While my work as a college counselor is to help bring out the best in my students, there is so much that goes unspoken. Being a competitive applicant to what I call “highly rejective” schools (schools with single-digit admit rates) takes an enormous toll on many students.

Keep in mind that “competitive” doesn’t mean “admitted”—it means that you’ll be evaluated alongside other applicants with straight A’s in advanced placement courses and a résumé boasting national-level achievements. (The vast majority of all these students will be rejected, because that’s the reality when a college has 2,100 spots and 45,000 applicants.)

Many of my students sleep less than five or six hours a night; many of them suffer from severe anxiety, or depression, or eating disorders, or OCD.

Over the years, I’ve seen a growing tendency to dismiss that as collateral damage—like, oh, that’s what happens when you’re bound for the Ivies or MIT or Stanford—but in reality, that’s a terrible way to live, and no school in the world is worth spending years obsessing about your GPA to the nearest hundredth of a point.

Even during the first two years of the pandemic, parents were panicking that the lockdown meant their children couldn’t participate in in-person extracurricular activities, and I remember thinking, “We are all going through this unprecedented, traumatic event—with repercussions we won’t even fully understand for years to come—and you’re worried about your kid’s EXTRACURRICULARS?”

In college application essays, there’s also an unspoken rule not to touch on the messy, difficult, potentially problematic aspects of a student’s life. The conventional wisdom is to avoid topics like divorce, mental health challenges, learning differences, or anything else that might flag a student as fragile or somehow damaged.

So the expectation—much like on social media—is that you put a glossy façade out to the world, and this is one of the reasons I wanted to be open and honest about my own experiences, warts and all.

(Since the ARC [advance review copy] came out, several people who have read it shared with me their own experiences with mental illness. I’m discovering that pulling back the curtain on my imperfect life seems to be giving permission for others to do so as well.)

Q: What impact did it have on you to write this book, and what do your family members think of it?

A: You know Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody #2, with its dignified, somber opening which builds into that insanely fast, toe-tapping, joyful friska? That’s what it felt like to write the book—ponderous and piercingly painful in some parts, punctuated by moments of surprising, chaotic joy in others.

It’s not like the book has a happy ending, but putting words to the truths about our family that I kept to myself for so long was incredibly cathartic.

And while I’m not proud of my flaws and failings as a parent, I did come to see myself as a link in an unbroken chain of other parents—in literature, in culture, in real life—who do what they think is best for their children and are subsequently shocked to discover that their children’s journey is not theirs to chart.

Bottom line: it was tough to write, but I’m so glad I wrote it. I’ve had many conversations I don’t think I would have had otherwise with my husband and all three of my kids—long, open-ended, sometimes revelatory conversations about success, about striving, about living in Palo Alto, about what we all might have done differently if we knew then what we know now.

It’s given us the opportunity to look at the hard truths of our life together, and as a result we’re both more honest and more tender with one another.

My daughter still insists that we should have had “better” children and that we’re just good at hiding our disappointment, but here’s the truth: we’re a highly irregular family. (I actually used a stronger descriptor when talking to her, but with tremendous affection.) I mean, we’re certainly not a regular family, whatever that might be.

But even amidst all our chaos and anguish and occasionally acrimony, we continued to love each other fiercely and to learn and grow. And sure, we’re a bunch of weirdos, each in our own way—when my daughter was little, she and I used to dance wildly and exuberantly in the kitchen whenever the friska in Hungarian rhapsody #2 came on—but we’re each other’s weirdos.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I’m revisiting a travelogue by two unjustly forgotten Soviet authors who went on a road trip across the US in the 1930s. I read it for the first time as a child in the Soviet Union and remember being utterly mesmerized by their descriptions of a world so different from everything I knew that it may as well have been another planet.

Now, after living in the US for decades—and in the context of some memorable trips I’ve taken, both solo and with various members of my family—I think there might be a collection of travel essays in my future.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: I was an avid watcher of Gilligan's Island (which I describe in an early scene in the book). What’s not described is one of my favorite moments, when Mr. Howell III, a stuffy, Harvard-educated millionaire, gasps, “Heavens, Lovey, a Yale man!” after the castaways capture a snarling, loincloth-clad jungle native.

My parents and I had been in the US for less than two years, and I had no idea why this was hilarious—only that it was. That I found this scene funny as a 10-year-old not yet fully fluent in English was a clear sign that I was destined to be a college admissions counselor.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment