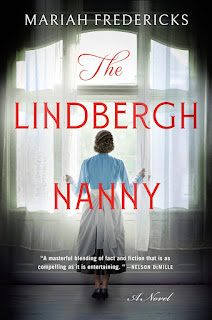

Mariah Fredericks is the author of the new historical novel The Lindbergh Nanny, which focuses on the kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh's young son in 1932. Fredericks' other novels include Death of a Showman. She lives in New York City.

Q: How did you first learn about Betty Gow, the “Lindbergh nanny,” and at what point did you decide to write this novel?

A: Like a lot of people, I first became aware of the Lindbergh kidnapping through Murder on the Orient Express, which was inspired by the crime. Many of the Morrow and Lindbergh staff were English or Scots and their treatment by the police elicited outrage in the UK.

It came up again in my reading with Little Gloria, Happy at Last and again when Maurice Sendak talked about being traumatized by the crime as a young boy.

The movie of Orient Express opens with the kidnapper in the Armstrong house. The only people who see him are the servants. So I was aware there were servants involved in the case.

But it wasn’t until my publisher asked me to do a historical standalone and I started thinking about what events were so compelling they could support a single book that I came back to the Lindbergh kidnapping.

But what new angle could there possibly be? I write a lady’s maid series, so I immediately thought of the servants. Who was the actual Lindbergh nurse or nanny? And that’s how I found Betty Gow. She was not only smart, young, and appealing, she was involved with the case at every point. Frankly, I’m amazed no one has done her story before now.

Q: The writer Nelson DeMille calls the book “a masterful blending of fact and fiction that is as compelling as it is entertaining.” What did you see as the right balance between fiction and history as you worked on the book?

A: Because this crime has been so studied and so passionately debated, I felt it was very important to stick as closely to the known facts as possible. The police suspected the kidnapper had help from someone on the inside, either in the Lindbergh or Morrow household. The novel offers a theory as to who that was. The theory has no weight if I bend the facts too far.

I also thought it was important not to take too many liberties with the characters themselves, especially the Lindberghs. A, they’re fascinating and complex enough. B, this was a loss experienced by real people. That demands a certain level of sensitivity and respect. In the book, Charles Lindbergh compliments Betty on her English; he actually did that. Anything unflattering is based on truth.

But I also took care to make the portraits balanced. Which any historical novel should do. The novel is told in Betty’s first-person voice, obviously that’s invented, though inspired by her letters and testimony. I changed one character’s backstory slightly; there’s already been pushback from some readers! But I’m comfortable with that choice.

Q: What are some of the most common perceptions and misconceptions about the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby?

A: I’ve been startled at how many people aren’t aware that someone was convicted for the crime. Some people strongly believe Richard Bruno Hauptmann was not guilty. Others think that the police investigation was incompetent. That Lindbergh himself was involved or other members of the family.

I won’t characterize which are perceptions and which are misconceptions. But those issues are addressed in the novel.

Q: How would you describe Betty’s relationship with Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh?

A: These are three people who did not know each other long. Betty was hired by the Lindberghs in 1931. Charlie was kidnapped in March of 1932 and found a month later. Betty was completely traumatized by the loss and the investigation. She returned to Scotland shortly after, coming back to America only in 1935 to testify at the trial. During much of her time with the Lindberghs, they were away or she was on vacation.

Yet because of the circumstances, they had a powerful, intense bond. Betty liked Anne very much. Admired her. Like many new mothers, Anne was a bit unsure of herself. Charles demanded that she not hover over the baby, that she continue flying with him. They were away for much of the time.

Flying and writing were extremely important to Anne, she loved being with her husband. But understandably, there were mixed feelings. Charlie was very attached to Betty and Anne felt that as a loss. At one point, she said how nice it was to hear him calling for her, rather than Betty.

In later interviews, Betty Gow called Lindbergh “something of a sadist.” The incidents that spurred that observation are in the book. He had very strict rules about everything, including child rearing. She disliked those rules and they seem cruel to us today, even though they were in vogue at the time and in keeping with how Lindbergh himself was raised.

However, he stood firmly behind the staff after the kidnapping, defending their innocence to the police and insisting that their privacy be respected. I have to think she appreciated that.

Also, Anne was pregnant when the kidnapping happened. Understandably, she retreated from the active investigation; the house was packed with police, she rarely dealt with them to maintain her sanity.

Lindbergh was deeply—perhaps controversially—involved. And Betty would have been his go to source for anything related to Charlie because, frankly, she knew the child best. In the novel, Charles Lindbergh looms more in her thoughts than he probably did in real life.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I just turned in my next manuscript, which is about the 1911 murder of the novelist David Graham Phillips. He was shot outside the Princeton Club, near Gramercy Park. At the time, he was considered one of America’s greatest novelists. His murder will be solved by America’s actual greatest novelist at that time: Edith Wharton. (I’ve made a few tweaks to this story!)

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: Charles and Anne Lindbergh were uniquely famous in their time. But because of social media, most people now have a public persona that is seen, known, interacted with, and judged. Researching and writing this book reminded me to be as positive and as kind as possible when engaging in the public space. We go to cruelty and toxicity with astonishing speed.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb. Here's a previous Q&A with Mariah Fredericks.

No comments:

Post a Comment