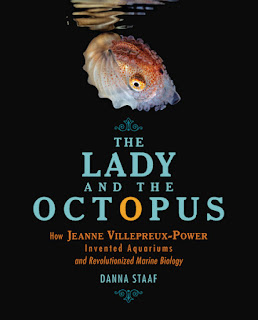

Danna Staaf is the author of The Lady and the Octopus: How Jeanne Villepreux-Power Invented Aquariums and Revolutionized Marine Biology, a new book for older kids. Her other books include Monarchs of the Sea. She lives in San Jose.

Q: What inspired you to write The Lady and the Octopus, and how did you first learn about Jeanne Villepreux-Power?

A: I first encountered Jeanne in Spirals in Time by Helen Scales, a wonderful book about the natural history of all kinds of seashells. I'm always intrigued to learn about female scientists in history, since women were often excluded from research or ignored despite their contributions. And Jeanne especially caught my attention because she studied octopuses, which have been my favorite animals since I was 10 years old.

Q: What would you say are some of the most common perceptions and misconceptions about octopi/octopuses?

A: One of the most common is how to pluralize the word! I used to have a strong opinion about the "correct" plural--the word "octopus" is derived from ancient Greek, and the ancient Greek plural would be "octopodes." But the word's ending is similar to many Latin words, and the Latin plural of such an ending would be "octopi."

However, it is now an English word, and in English we would pluralize it "octopuses." That's the plural I personally prefer, but I don't correct people who choose a different one. We're all talking about the same color-changing, shape-shifting, puzzle-solving, mind-blowingly amazing creatures!

The other most common question and comment I hear is about the intelligence of octopuses. Like plurals, there are a lot of different ways to think about intelligence.

Octopuses can learn and remember how to solve puzzles; they can recognize themselves and other members of their own and different species. Compared to other animals, they have large brains and a huge number of neurons, although many of these neurons are distributed throughout their arms rather than concentrated in their brains.

Instead of trying to figure out whether an octopus is "as smart as a cat" or "as smart as a crow," scientists are more interested in studying "What does intelligence look like when it's spread throughout an animal's body?"

Q: The School Library Journal review of the book says, in part, that "this author is as resourceful and ingenious in relating the story of her subject as Jeanne Villepreux-Power was in her scholarly endeavors." What do you think of that assessment, and how did you research the book? Did you learn anything that especially intrigued you?

A: I was incredibly honored by the comparison between my work and Jeanne's! I admire Jeanne's creative thinking, tenacity, and attention to detail, so this was really quite a compliment for me.

My research for the book was mostly conducted on a computer, since the pandemic prevented me from visiting the places in Europe where she lived and worked, but I communicated over e-mail and phone with several scholars in France and Italy who were extremely generous and helpful.

I read all of Jeanne's papers on marine biology, in both French and English, and some excerpts of her other writing (like the travel guide she wrote for Sicily).

In one of her papers, she mentioned acquiring a pet tortoise, after attempting to preserve it as a scientific specimen! According to Jeanne, the tortoise survived a full day immersed in alcohol, which seemed so wild to me that I reached out to ask a herpetologist if that was possible. He responded that turtles are "gnarly" and said, "I'm not even surprised."

Q: What do you see as Jeanne Villepreux-Power's legacy today, and what do you hope readers take away from the book?

A: A pioneering inventor as well as marine biologist, Jeanne is certainly one of the people that we can thank for having aquariums in the world today. She didn't call her inventions "aquariums" because that word hadn't been coined yet, but her glass and wood cages allowed sea animals to be kept alive and healthy for scientific observation for the first time.

She was also the first female member of numerous European scientific societies, helping to pave the way (which would remain bumpy for some time) for generations of women to come.

I hope that The Lady and the Octopus sparks young readers’ curiosity about science and nature. Rather than seeing science as a series of facts to be memorized, they may come to understand it as a deeply human process—and one that they can choose to take part in, whatever their background or situation.

I also hope the book will illuminate for readers of all ages the many connections between seemingly disparate fields: science, art, history, engineering, social and environmental justice. We live in a world wide web, offline as well as online, where all aspects of human learning link to each other, and to the lives of our fellow non-human Earthlings.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I'm writing a book called Nursery Earth: The Wondrous Lives of Baby Animals and the Extraordinary Ways They Shape Our World that will be published next spring and is available for pre-order now.

I've been jokingly calling it "a baby book for Mother Earth," but really it's a baby book for all of us, even people with no interest in human babies. At any given moment, most of the animals on the planet are, in fact, babies--from chicks and tadpoles to caterpillars and larvae. As these small creatures grow and migrate, they create links between ecosystems and build the environment of the future.

They're both incredibly vulnerable and incredibly vital, and I hope the book will help readers appreciate fly maggots as much as ducklings.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: For anyone interested, I have a monthly newsletter called The Octopost: all the news that's fit to ink! It includes cool new discoveries in octopus and squid science, updates on my own projects, and often a silly little comic that I've drawn.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment