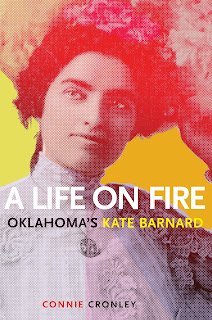

Connie Cronley is the author of the biography A Life on Fire: Oklahoma's Kate Barnard. Cronley's other books include Sometimes a Wheel Falls Off. An enrolled citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, she lives in Tulsa.

Q: What inspired you to write A Life on Fire?

A: I was a young woman in my 30s when I met Oklahoma’s premier historian, Dr. Angie Debo, who was in her 80s. She became my friend and mentor until she died at age 98. We talked a lot about writing. She told me about Kate Barnard, the first woman elected to state office in Oklahoma in 1907—15 years before women’s suffrage.

Kate was a heroine of the Progressive Era and such a bright star of social reform in the early 1900s that the national press called her “The Good Angel of Oklahoma.” A writer at the time said she was one of America’s great women, fighting for social justice and economic liberty with invincible courage. Her compassion burned like a flame, Angie told me.

Kate dedicated herself to political and social reform on behalf of orphans, the mentally ill, the incarcerated and the poor. Her special interest was children. She influenced Oklahoma to enact laws that kept children out of the mines, the mills, and the factories, to provide public education and to establish a juvenile justice system.

She

was a tiny woman, not much larger than a child—5 feet tall, 90 pounds—but

absolutely fearless in her political campaigns. She had dark hair and deep blue

eyes and looked much like Helena Bonham Carter in A Room With a View.

Kate never married and had no children of her own but the cause of the child was her foremost mission. She dressed plainly and never wore jewelry. She was famous for saying, “How can women wear diamonds when babies cry for bread?”

Angie and Kate were contemporaries and she described hearing Kate speak publicly. “She had a power over an audience that was completely, absolutely hypnotic,” Angie said.

She had followed Kate’s spectacular rise to fame and witnessed her political crash. She learned much more about that downfall when she was researching her landmark book And Still the Waters Run about the destruction of the Five Tribes in Oklahoma. I learned more about it, too.

Q: How did you research the book?

A: Dr. Debo—I never called her Angie—said she would like for me to write a biography of Kate. I agreed on the spot and began by tracing Angie’s footnotes in And Still the Waters, research that took me to Washington, D.C. (the National Archives and Library of Congress), then to Oklahoma universities and libraries, and to Texas, Kansas, and Missouri.

It was lucky that I started research when I did, in the mid-1970s, because I found people who had known Kate. This was before computers and online research. Copy machines were still rare. Eventually I collected nine banker’s boxes of materials.

Kate grew up in Kirwin, Kansas, so I contacted people in that area for help. These generous people, ordinary citizens, dug into newspaper archives, old school records, genealogy and their own memories to find information for me.

When Kate was two, her mother died in childbirth and one of her searing memories—one that I’m sure influenced her career—was her mother’s funeral on a snow-covered Kansas cemetery. A man went out into that cemetery, found the mother’s gravestone and took a Polaroid photo. It’s in the book. Probably all of those people are gone now but I am forever grateful for their kindness.

After several years of research, I changed jobs, life got in the way, and I had to set the project aside, but it was never far from my mind. When I retired a few years ago, I dusted off the boxes of research materials, brought myself up to date with current information, and vowed to finish the book and keep my promise to Angie.

Q: What did you learn in the course of your research that especially surprised you?

A: The biggest surprise was the onslaught of public attack unleashed on Kate. She had been the state’s darling with her work in social reform until she agreed to take on what was called the Indian Problem.

When the Five Tribes were dissolved and communal land was divided into individual allotments, the Natives became owners of property with mineral rights and timber valued at billions in today’s money. They were being defrauded by greedy whites in widespread corruption by every means imaginable: forgery, embezzlement, bogus marriage, kidnapping and murder.

Angie wrote that this was “an orgy of plunder and exploitation probably unparalleled in American history.” I write about it in more detail in A Life on Fire.

Kate was the only state official with the legal authority and the courage to defend Indian orphans being robbed of their property. She stood between the grafters and enormous Indian wealth: she became a marked woman. Corrupt attorneys, judges, businessmen and other people closed forces against her and the state’s legislature joined them.

They could not eliminate her office because it had been created by the state constitution, but what the legislature could do was cut funding for her office. In 1914 they did that. It ruined her department, her health and her life. She was an invalid and recluse until her death in 1930, but before she died she vowed to regain her health and return to fight for those of Oklahoma with no voice of their own.

Q: Author Randy Krehbiel said of the book “The story of Kate Barnard is as wonderful and heartbreaking as the story of Oklahoma.” What do you think of that description and how would you compare her story with that of the state today?

A: Randy is a great political reporter and historian. He is accurate in his description. Kate burst into the public in 1906 as Oklahoma was preparing to become a state. She united farmers and miners into a powerful political block and she helped write the state constitution that was so progressive national press described the new state as a new kind of state because it was so caring for its citizens.

However, modern mental hospitals, compassionate orphanages, progressive jails and prisons are expensive and the populace, suffering with drought and economic depression, lost interest. Then came the temptation of Indian moneys and greed replaced compassion.

Kate identified education, criminal justice, mental health care, and support of the needy as hallmarks of a great society. She recognized Native American rights.

Those are still issues in the Oklahoma news today, but unfortunately the state ranks near the bottom in all of those areas. The exception is the Five Tribes, which are flourishing despite the state’s antagonistic attacks on them. The eclipse of Oklahoma’s bright promise would break her heart, but she would not give up.

Chad “Corntassel” Smith, former principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, said “Sadly, now more than ever, Oklahoma needs Kate Barnards.” The chief is right. Kate was a tiny woman of great moral courage. Locally and nationally we need selfless politicians like Kate, visionaries with moral courage.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: A Life on Fire is still bobbing around on the Oklahoma best seller list and the Oklahoma Historical Society has named it the best book of the year. Interest in Kate Barnard is high and that keeps me busy talking to groups and doing book signings. This makes me happy; I want more people to know about her.

I especially want young people to know about her. Kate said in her final national speech, “The youth of Oklahoma, seeing the fight that I am making, will, when I am dead, take up the banner where I drop it and march upward toward the heights. No battle for justice was ever lost.”

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: I have come to believe that Kate Barnard is the greatest woman in our state’s history. After reading the book, people ask my “Why have we never heard of her? How did we not know this history?”

I think the answer is because she fought a heroic but losing battle on behalf of Native Americans. It is the winners, not the losers, who get to write history. Nobody has been anxious to write the story of that shameful episode in our state’s history.

Another question I am asked frequently is “When is the movie about her coming out?” I hope that happens. Her life was so dramatic and cinematic it would make a great movie.

Until then, I kept my promise to Dr. Debo and to myself and have told the story of Kate’s life in my book.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment