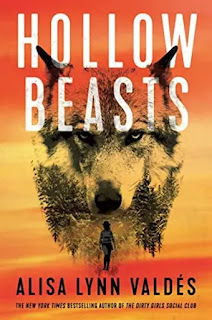

Alisa Lynn Valdés is the author of the new novel Hollow Beasts, the first in a new series. Her other books include the novel The Dirty Girls Social Club. Also a journalist, she lives in New Mexico.

Q: What inspired you to write Hollow Beasts, and how did you create your character Jodi Luna?

A: A few things inspired me to write Hollow Beasts. The idea first came to me several years ago when I befriended a game warden. I was surprised to learn that being a game warden was the No. 1 most dangerous job in law enforcement in the United States. As a former reporter, this fascinated me because so little police reporting addresses the unique dangers and challenges faced by conservation officers.

The reasons their job is so dangerous are that they work alone, in thousands of square miles of vast remote wilderness, often in places without cell or radio service, and they police poachers, who are entitled, armed people who don’t mind breaking the law. For a woman to be a game warden, the stakes are even higher, as most poachers are men.

My love for the outdoors inspired me as well. As an avid hiker, trail-runner, and camping enthusiast, I spend most of my free time outdoors in rural New Mexico. My early childhood was spent in a tiny adobe house in rural New Mexico, and in my mid-life, after many years away working in cities like Boston, New York and Los Angeles, it was the rugged beauty and unique culture of rural New Mexico that called my soul home again.

I had just moved back to New Mexico when my first novel was published nearly 20 years ago, and in Hollow Beasts and the Jodi Luna series generally, I am finally allowing myself to tell the story of my place, my people, in this unique and misunderstood corner of the nation, where my family has been for 11 generations.

During a long hike in the Cibola National Forest, the character of Jodi Luna came to me, in 2020. I was in a kind of mourning for the world, gazing out across the mountains at the gash of a cement mine, thinking about climate change and the great bird die-off.

I felt trapped in a world gone mad and said sort of a silent apology prayer to the wild things, for the damage wrought by my species. I wished we had a hero who could do something about the short-sighted narcissistic self-destructive drives of human beings, who foolishly see themselves as separate from everything else.

Jodi just landed, fully formed, in my being that day, almost as a gift from the universe. The hero I needed. It’s hard to explain. Sometimes writing feels a bit like channeling, like being a conduit for stories that want to be told.

Jodi is for sure one of those characters I feel was pulling on me to help her into existence. I felt Jodi’s spirit commanding me to create a new kind of Southwestern or Western hero. Sounds pretty grandiose when I say it out loud, but it didn’t feel like that. It felt like stumbling upon a wood sprite who wanted to tell me her story. And what a story it was. I fell in love.

She was a celebrated nature poet who, in her own mourning for the wild places and things, decided to walk away from academia in order to combat overconsumption and exploitation of nature on the front lines. She was, in a way, who I wanted to be. Maybe she is who I am deep down inside. If I were younger, I’d absolutely be a game warden now that my son is grown and I’m on my own. I’d risk it all, for mother earth.

Jodi wanted to be born because America needs a new kind of western hero. A more honest one. One who lives in harmony with the natural world, rather than as a rugged individual up against it. She was the voice of my ancestors in this place, calling me home, reminding me of all that we have forgotten as a species in the wake of colonization here.

As much as I love Walt Longmire, Joe Pike, and Costner’s Yellowstone, the prevailing western heroic narrative is still far too centered around stoic white men at war with nature and non-white people.

That narrative has always been pure fantasy. Their kind weren’t here in the Southwest first. My kind were. Books, films, and TV series about the American West are unfortunately still stuck in a fundamentally racist paradigm first set forth by noted white supremacist John Wayne, who wasn’t a cowboy, but a Hollywood actor.

The very word “cowboy” is rooted in the vaquero tradition of Spanish-Indigenous people. The words chaparral, rodeo, even barbecue, all have Spanish roots. And yet the “outdoorsman” world in the US has embraced and amplified the white-dude Wayneian mythos as “truth,” when it could not be further from it, especially here in New Mexico.

I’m sure this will all be misconstrued by those in power as some kind of reconquista, but that’s only because they’ve probably never spent time in the small towns in the mountains of Northern New Mexico, where Jodi’s world is simply reality. My reality.

I started thinking about how indigenous and Hispano communities in my state have traditionally approached the concepts of the outdoors, of land, of hunting, of fishing, of farming, of community, of the place humans hold in this vast and beautiful wilderness.

There is a reverence, among our people, for nature, a humility before the wild world, a communal approach that includes all the living things, that I find totally lacking in the way white male western heroes are painted in the American imagination.

This is where Jodi walked in. She is here to bring reality back to the conversations about the outdoors, about hunting, about morality, about nature, about balance, about compassion and empathy for the sentience of all living things.

I am not against hunting for food. I do so myself. I’m against bragging about your kills, posing with an animal you’ve shot, as it bleeds to death, grinning like a freaking serial killer. I believe that the entire “look at what a macho piece of crap I am” ethos is the last acceptable bastion of colonialism, treating the majesty and sacrifice of our fellow animals like a goddamned video game.

The United States culture is big on false binaries, where the only alternative people think exists to the trophy hunting a-hole is militant veganism. Through Jodi, I show that there’s another way to be - a moral, ethical hunter, who never takes more than she needs, who thanks the earth for its bounty, who honors the spirits of the animals she protects and, at times, within balance, within reason and against the horrors of factory farming, chooses to consume.

Not a sadistic omnivore, not a reluctant omnivore. A reverent omnivore who understands she, too, is part of an interdependent web of life.

Jodi Luna is, I feel, the rugged, solitary (but not individualistic) western hero we need, because she does not conform to the colonialist “man versus nature” view of the west that has gotten us to the point of no return with environmental degradation and climate change.

Jodi is the spirit of all the beautiful, fierce, wild, and ethical things we used to be in the Americas, before contact, before colonization and industrialization nearly ruined everything. She goes to war against all the forces I wish our society would go to war against, in defense of the defenseless, the voiceless, the meek. And she wins.

She is my ferocious call, as a woman, as a mother, as a human being who mourns for what we’re doing to the earth and ourselves, for us to reconsider our ways, before it’s too late. And she does this in a Carhartt, Justins, and a Stetson. Badass.

Q: This is your first thriller--was it a different writing experience from your previous novels?

A: I am so excited to be writing thrillers now! I have long been a huge suspense fan. It is pretty much all I read.

Dean Koontz is by far my favorite writer and has been since I was in college. He is truly a genius, and so many synchronicities have happened to me while reading his work that I feel he is also powerfully connected to Source, to the magic that is the channeling of writing, so much so that his connectedness reaches through to his readers.

He’s a survivor, a social critic, funny, caring, loving, spiritual. All the things. And he still manages, in the end, to do all those things while also delivering beautifully written stories with magnificent plots and characters we root for. This is all what I strive to do, as well. I cannot tell you how much I happy danced when Hollow Beasts was bought by Thomas & Mercer, Koontz’s publisher. Absolutely dream come true stuff.

When I first landed in book publishing 20 years ago, as a writer of commercial women’s fiction (known then by the ugly nickname “chick lit”), I was 32 years old. I’d spent the prior eight years as a staff writer for The Boston Globe and the Los Angeles Times.

Being a daily news reporter is a great training ground for any kind of writing, because it teaches you to listen, to observe, to research complex truths and then deliver them to readers in clear, engaging prose written quickly and without any attachment or preciousness.

I was married back then, an ambitious young professional who was making a life for herself in big cities. I wore heels and lipstick as I chased ambulances. So chick lit was a genre that felt important to me then, relevant to me then. It was who I was, at that time. I had lots to say there and am fortunate that St. Martin’s Press gave me the chance to say it, over several books in that genre.

But in the end, I felt I’d said what I’d needed to say there and was ready to move on to other things. I think of the time the great jazz saxophonist John Coltrane was performing live and someone yelled out, requesting he play “My Favorite Things,” and he responded with, “That’s not one of my favorite things anymore,” and did not play it.

As artists, we move. We grow. We change. To expect a woman of 53, who has weathered a painful divorce and raised a son on her own, who has returned to rural New Mexico after realizing the pointlessness of the rat race in big cities, to keep writing about young women making their way in the big city is a form of artistic suffocation.

I have something new to say now, and I believe the readers who have stuck by me all these years will also have grown and changed and desire something new.

From a craft standpoint, suspense involves a great deal more meticulous plotting than chick lit did. So that has been fun and challenging. Emotionally, there is a greater range in suspense, for me. The stakes are much, much higher than they were in the plots of any of my previous books. Life and death.

I also really, really love getting inside the heads of my villains. In suspense they can be absolutely horrible, and that’s sort of fun to write, as long as they get what’s coming to them in the end. And with Jodi, they do.

Transitioning to suspense feels like a natural and important progression for me, and I am deeply grateful to Thomas & Mercer, and specifically to my editor, Liz Pearsons, for giving me this chance to explore a new genre.

Q: The novel takes place in New Mexico—can you say more about how important setting is for you in your writing?

A: In Hollow Beasts, setting is everything for me. The land that Jodi has returned home to, in order to protect it, is nothing more and nothing less than the goddess of Mother Earth. Madre Tierra. This is the physical and cultural land that made her who she is, one of the last great wild places in the United States, a land and culture that are both under siege from capitalist development, climate change, overconsumption, and colonialist exploitation.

Rural northern New Mexico is a real place, but it’s also highly symbolic of all the important and good things that we’ve forgotten as a society, a microcosm for those of us who are trying mightily to stop our species from making our planet uninhabitable for ourselves and most other living things in the name of consumerism and materialism. The setting is beautiful, but fragile. Like our earth. Like us.

Q: How was the book's title chosen, and what does it signify for you?

A: The title was chosen as a double entendre. The bad guys in the book are domestic terrorists, hiding out in the national forest, poaching wildlife, and, horrifically, kidnapping brown women, hunting them like animals as a sort of test of loyalty, to gain entry to the group.

They are camped out in a literal hollow, where beasts, namely Mexican gray wolves, are known to live, and the group leader is obsessed with killing these endangered animals. So, the hollow beasts are the wolves, as beasts, in the best sense, who live in the hollow. But it also refers to the terrorists themselves, as beasts in the worst sense of the word, and spiritually hollow, without empathy.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I’m working on three things at the moment. I’m finishing up edits on the Jodi Luna book two, called Blood Mountain.

I just finished writing my first stage musical (my undergraduate degree is in music, from Berklee College of Music in Boston) for Urban Theater, a Puerto Rican Theater in Chicago, and we are about to begin workshopping that. I wrote the libretto and the songs, both.

And I’m cobbling together a stand-alone suspense novel unrelated to the Jodi Luna series, set in Patagonia, which, after northern New Mexico, is my favorite place on earth.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: Yes! I’m excited to announce actress and producer Gina Torres has reached out to say she wants to make Jodi Luna into a TV series. It is going to be so amazing to see a strong woman of color and a woman of middle age in that fierce western hero role, on the screen.

New Mexico has great film incentives and often stands in as other places - for instance, Longmire was shot entirely in New Mexico as a stand-in for Wyoming. It will be wonderful to finally see New Mexico proudly playing itself, with heroes who actually look like the people who live here.

Also, the National Hispanic Cultural Center has selected Hollow Beasts for its prestigious book club, for April 2023. All good things!

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment