|

| Photo by Tina Krohn |

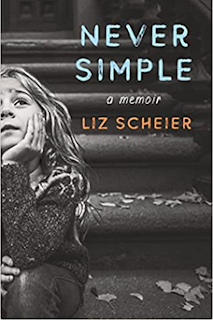

Liz Scheier is the author of the memoir Never Simple, which recounts her relationship with her mother. Scheier is also a product developer for an educational nonprofit, and she lives in Washington, D.C.

Q: On your website, you say that when you started your writing project that became this book, “My only criteria was that it would not be about my mother. Two years later I looked up to find that I had written a complete manuscript that was entirely about my mother.” Why do you think it turned out that way?

A: It turns out that when something really huge is happening in your life, you have to write about it. I was on maternity leave with my second child. My mother’s eviction proceedings were heating up, and the calls were coming in. I needed someplace to put the fear, rage, and love. It was like a therapy journal. A year into the project, she died--to me, very suddenly. I had 50,000 words, which was half a book.

When I had my first child. I was looking up books about how not to pass on the trauma of your life to your child. I wanted to [write something like] that.

Q: How was the book’s title chosen, and how would you describe the relationship between you and your mother?

A: I submitted the manuscript to my agent under the title “Liar.” His husband came up with “Mother of Invention.” Then two other books with that title came out! My agent found an Oscar Wilde quote, “The truth is rarely pure and never simple.”

Our dynamic was pretty challenging. She had a number of diagnoses, and the one that stuck was borderline personality disorder. It’s like narcissistic personality disorder. The defining characteristics are a terrifying fear of abandonment, a shuttling between rage and panic, and the inability to retain relationships you care about. You end up pushing people away.

Adults can say they don’t want to be in a relationship [with someone like that] but children can’t. As an adult, I was supporting her. I separated at various times. After my first child was born, I couldn’t function with a dozen phone calls a day.

It was not easy to separate. She was unable to see me as a person separate from herself. It’s easier to say, “I’m not going to pick up the phone” when she was calling from her apartment, but more difficult when she was in a New York City shelter.

Q: How did writing the book affect you?

A: It was comforting at times to put it on paper. The story can be a morass in your head, but when you put it in a story, it’s easier to grasp.

Once the book was published, I had three buckets of reactions: from close friends and loved ones who knew most of the story; from acquaintances in book clubs and other friends; and from strangers on the internet.

Three or 4 percent of the people were saying, “You’re a terrible person, you’re the abuser,” which is hard to hear; when you sort of believe that, the comments hit. I let my mother go to a homeless shelter. There was no good option.

But the vast majority of responses have been very kind. People saying, “I also was raised by a single mother with borderline personality disorder. Thank you for telling our story.”

Q: In The New York Times, Elisabeth Egan writes of the book, “Scheier approaches her childhood like a detective...going room by room, block by block and year by year as she points out the cracks between the fiction she was raised with and the facts she pieced together on her own.” What do you think of that description?

A: It’s a beautiful description. That’s what it felt like at the time. A detective is an apt description. I don’t always trust my own perspective, but if I have documentation, it means a lot.

Q: What do you think the book says about the impact mental illness can have on a family?

A: At the time I wrote the book, I didn’t know the term “cycle breaker.” I was trying to tell my mother’s story without making her into a monster. People with mental illnesses are not monsters. She struggled every day of her life. But there was a negative impact on the people around her, including me.

There’s been a pushback recently on the idea that “your family is your family”—now, any toxic relationship is a reason for severance. For most people, either extreme is not the most realistic one. We’re wobbling around in the middle trying to find the right balance. There’s the idea that [the action you take] need not be for all time.

Q: Can you say more about the term “cycle breaker”?

A: Many illnesses become generational, even if they’re not genetic. My grandmother suffered from trauma and developed a disorder. My mother was raised in disorder and developed a disorder. I did not develop the disorder. It’s about how to parent children and stop the cycle.

Q: What do you hope readers take away from the book?

A: I hope readers take away the importance of giving each other grace and giving themselves grace. I was speaking to a group about eldercare when the elder has mental illness. Caring for an elderly parent is never easy, but it’s more complicated when the parent has been abusive.

In a “normal” relationship, they cared for you, so you care for them. In a flawed relationship, that assumption is severed. [There’s a question of how] you can live up to the relationship without destroying your own family.

Q: Are you working on another book?

A: I’ve finished a novel and submitted it to my agent.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: The abuse of children can seem salacious. I’m trying to get across a more

complicated dynamic.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb. Liz Scheier will be participating in the Temple Sinai Authors Roundtable on March 25.

No comments:

Post a Comment