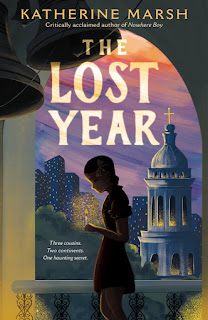

Katherine Marsh is the author of the new middle grade novel The Lost Year. The novel is set in Ukraine in the 1930s and in the United States during the Covid pandemic. Her other books include The Night Tourist. She lives in Washington, D.C.

Q: The Lost Year was inspired by your own family history--how much did you know about that history growing up, and at what point did you decide to write this book?

A: I grew up in the home of my Ukrainian grandma Natasha. I was an only child so we spent a lot of time together and she corresponded by airmail with her family in Soviet Ukraine and shared lots of stories about her childhood there.

So I knew from an early age about the Holodomor, or the Ukrainian famine of 1932-33. My grandma also had a younger relative who immigrated in 1933—which was quite unusual--and was a Holodomor survivor and lived to 106! I was always shocked by her description of the village during the famine—how quiet it was because all the animals, even the cats and dogs, had been eaten by the starving.

I decided to write about this in late 2019 because although this was common knowledge to me, almost no one in America seemed to know it happened. Like you, Deborah, I’m also a journalist so I was simultaneously interested in writing about the ways in which the Holodomor is a case study in disinformation, something that continues to be a huge problem today. The story has an important media literacy component.

Q: How did you research the Holodomor, and did you learn anything that especially surprised you?

A: I spoke to family both in the US and Ukraine, including the children of the

Holodomor survivor in our family who made it to the US. One of my relatives

still in Ukraine went to the library/museum in our village but there was no

records about the famine. This is typical—the Soviet Union suppressed this

history.

My cousin did share oral memories passed down by his grandma, my grandma’s sister. There are also other oral histories that have been preserved and I read many of them, also about a dozen scholarly books that deal with the Holodomor. I had three historians read the book and help me with historical accuracy.

In terms of what surprised me: That Stalin issued internal passports in the middle of the famine which prevented starving Ukrainians from traveling to find food. I always knew this was a man-made famine but the extent to which the Kremlin ensured death from starvation was shocking.

Q: In an interview with Publishers Weekly, you said, “I wanted to include [present-day character] Matthew because I was getting worried that the book would seem remote to readers, both historically and geographically. I wanted to make a stronger connection to contemporary readers.” Can you say more about why you decided to include this timeline set in 2020, during the pandemic?

A: I started the story before the pandemic but within a few months, I was stuck

at home with my own kids, who were in middle school and upper elementary, as

well as my 87-year old mom, whom we took in. (Like Matthews’s mom, I was doing

a lot of caretaking.)

A million Americans died in the pandemic and even if you didn’t lose someone, many kids and adults alike were dealing with fear, isolation, disruption, anxiety, and the sense that nothing like this had happened in our lifetimes.

This is where I think having a sense of history is helpful—history is full of traumatic periods that teach important lessons not only about how not to repeat horrific history (my father’s family is Jewish so the Holocaust also loomed large for me as a child) but about witnessing, memorializing, survival, and resilience.

My intention was not to make an apples-to-apples comparison between something like the Holodomor and Covid; they’re very different. Rather my contemporary character, Matthew, learns to process what he is going through and to find purpose by getting out of his own challenging time period and head and thinking about another time period and person (namely, his Ukrainian great-grandma).

Q: The writer Veera Hiranandani said of the book, “Marsh shows us how deeply connected we are to our past and that in the middle of a societal crisis where disinformation is rampant, the ultimate truth can be found in the relationships we hold dear.” What do you think of that description?

A: It’s spot-on. Veera put her finger on the pulse of this book. An

understanding of history allows us not only to reckon with the past but to make

connections in the present.

I love Veera’s The Night Diary because it presents complex and difficult history through that lens of family relationships. I wanted to do the same with The Lost Year.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: This was a heavy and painful topic so my next book is lighter although like all my books has something to say about the world we live in. It’s called The Myth of Monsters and it’s a series of feminist retellings of the Greek myths. Book One is about a girl related to Medusa.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: I’ve visited a number of schools already on book tour and at every single school—urban or suburban or rural--kids know what is happening in Ukraine. This is why it’s ever more vital to give them The Lost Year and a better sense of Ukraine’s 20th century history, especially as there are important historical through-lines between the Holodomor and what is happening between Russia and Ukraine today.

If you are an educator, please get this book into your classroom and check out the educators guide. Also, kids and adults alike will be challenged by the mystery at its center which kept The New York Times book reviewer “on the edge of [her] seat.”

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment