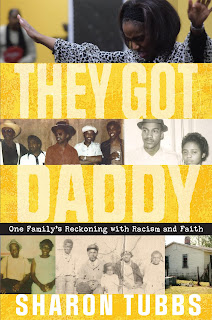

Sharon Tubbs is the author of They Got Daddy: One Family’s Reckoning with Racism and Faith. She lives in Indiana.

Q: How did you first learn about the white supremacist attack on your grandfather in 1959, and why did you decide to write this book?

A: I was in elementary school when my mother mentioned that my grandfather, Israel Page, had been kidnapped by the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama. We were watching the news and a story flashed on screen about the Klan and a permit to march somewhere in Indiana.

This was the 1980s. I had white friends in class at school and nice white teachers, too, so I was shocked that the evil people in costumes from historical documentaries still existed. But my mother verified that they most certainly did. As a matter of fact, she said, “They got Daddy,” referring to my grandfather.

She didn’t recall details of how the tragedy unfolded, nor did several relatives I would interview in the years to come. They just knew that it happened, but I could read the sadness in them for what their father had gone through.

This knowledge stuck with me, and I would mention the ordeal in essays during middle school and college where I pursued a degree in journalism. At some point, one of my uncles revealed that it all began with a white sheriff’s deputy ramming my grandfather’s car in an accident. My grandfather lost the use of his arm and the ability to continue working as a well driller to support the family. He sued the deputy, which eventually led to his kidnapping the day before trial.

In my first career as a newspaper journalist, I learned the elements of a good story, such as the characters, plot, and conflict or tension. This slice of my grandfather’s life held those elements, and I knew I had to be the one to tell the story.

Q: How was the book's title chosen, and what does it signify for you?

A: My mother’s words during the news broadcast, “They got Daddy,” stuck with me through the years, coaxing me to discover what happened to my grandfather and who was involved. Still, those words weren’t the first title I chose. For some time, I called the manuscript “Preacher” since my grandfather was a church pastor and many people, including my grandmother, actually called him “Preacher.”

“They Got Daddy” came about only as the story took its final shape, just before I sent it to prospective publishers. By then, I’d realized the story was not just about my grandfather, but about the trauma of his kidnapping and injustice that filtered through our family line.

The more I learned of our history, the more I reflected on my own experiences with injustice and discrimination. I recall driving to Indiana University for the first time since graduating 25 years earlier. From Fort Wayne, I had to drive south through the city of Martinsville, which had a reputation for racism during my college years.

Back then, myself and other Black students timed our travel to avoid driving through Martinsville after dark. Now, decades later, I’d forgotten to take such precautions. Darkness fell just as I passed a sign announcing my entry to “City of Martinsville.” Fear came over me. I was hungry, but couldn’t stop for a bite to eat, not here.

In that moment, I didn’t feel safe. I realized that years of microaggressions and racist acts had left me culturally traumatized, that I had this fear of getting “got” by evil white people who no longer wore costumed sheets.

Such reflections made the title “They Got Daddy” easier to relate to and more personal. It signifies the fear or dread within many people of color that someday we might get “got” by the “theys” of our society—the white supremacists, the closeted racists, the unjust systems of oppression.

We don’t know the identities of my grandfather’s kidnappers, but that doesn’t matter so much now. “They” seem to be ingrained in the system, then and now, and parts of our lives as African Americans is shaped around not allowing them to get us.

Q: The NPR critic Eric Deggans said of the book, “Lots of writers have tackled America's historic abuses of Black people and Black families. But few handle the subject as deftly as Sharon Tubbs, whose They Got Daddy connects the trauma which reverberated through her own family history when her grandfather was abused by powerful white people, to the larger history of Black America's attempts to survive similar oppression.” What do you think of that description, particularly about the reverberations through your family?

A: I’m grateful for Eric’s description, because he is dead-on in capturing the traumatic reverberations through our family. The pain and anger of what my grandfather endured lingered with my uncles and aunts when I interviewed them 50 years later.

They had rarely spoken about the matter, nor did they recall specific details, but they remembered that their father had been kidnapped, beaten, and humiliated. They knew that justice had not prevailed in his case.

One uncle said the ordeal compelled him to move to Indiana, in hopes of escaping the maltreatment of the Jim Crow South. Most of his siblings followed him there, during the 1960s, moving from Alabama to the Midwest. Yet, the experience of that accident, the kidnapping, and all that they entailed stayed with them, permeating their worldviews of life in America.

There is growing evidence that trauma is passed through family DNA. In other words, our bodies literally adjust to deal with the tragedies we suffer, and we pass along that adjusted makeup to our children biologically and culturally. While writing the book, I reflected on how the ordeal affected my mother and her siblings.

Also, several of my own traumatic experiences surfaced. I wondered if my responses resulted from the trauma passed down through the family. I included those reflections in the book, which is what Eric referred to in his description.

Q: What do you hope readers take away from the book?

A: I hope the book evokes an awakening among readers. That awakening could take different forms, based on their own experiences with racism or privilege or injustice.

For instance, an African American reader says the book unearthed memories of an injustice she endured. She realized bitterness simmered within her and she then took steps to forgive and find her own sense of freedom.

A white reader who reached out to me said the book evoked memories of growing up in a racist family. She recalled behaviors she engaged in to fit in with relatives. Ultimately, she walked away from their perspective of Black inferiority. The book seemed to validate her decision to shun the closeted racism those around her practiced. It also answered questions, she said, about Black people and the strength of faith, drawing her closer to understanding.

Many people don’t like to talk about the uncomfortable topic of race, but I believe this book will compel those of different ethnicities to be courageous enough to face my family’s truth and to look within. If they do, the stories and various angles presented in They Got Daddy will, hopefully, awaken them to something positive that they can do to make society a little bit better where they are.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: Currently, most of my time is dedicated to being the director of a nonprofit that provides health education to underserved residents in Fort Wayne, Indiana. But I’m always writing on the side.

My books have been faith-based fiction and self-help in the past, but They Got Daddy took me back to my journalism roots of research and storytelling. I want to continue researching people’s stories and telling their truth. I have an idea about my next subject, but it would be premature to discuss it publicly.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: Anytime I talk about this story, I want people to know that the Black experience and the book, itself, are about more than the struggle to overcome racism. The strength of our story lies in our faith, pride in who we are, familial bonds, humor, and love for one another. I don’t want anyone to think that They Got Daddy doesn’t convey those foundational strengths of African American culture, because those are the experiences foremost in my mind and heart.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment