Photo courtesy of Cristobal Vivar

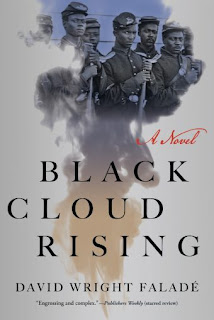

David Wright Faladé is the author of the new novel Black Cloud Rising. It focuses on the Civil War experiences of the historical figure Richard Etheridge. David Wright Faladé's other books include Fire on the Beach, and his work has appeared in a variety of publications, including The New Yorker and The Village Voice. He is a professor of English at the University of Illinois and the Mary Ellen von der Heyden Fellow at the New York Public Library's Cullman Center.

Q: You've already written about Richard Etheridge in your nonfiction book Fire on the Beach--why did you decide to return to his story, and why as a novel this time?

A: The story at the heart of Black Cloud Rising required that I tell it as fiction. Even more than just an account of former slaves becoming soldiers, I was interested in attempting to tell the story of slavery itself in the novel—the personal story of slavery. Richard Etheridge was his former owner’s son, so what more complicated and conflicted story exists than that!

In official documents and in his post-war census records, Richard was identified as “mulatto,” or mixed-raced. So-called “miscegenation” was taboo in that era, so mixed racial heritage was largely denied or obfuscated, particularly by whites.

But his former owners, white Etheridges, described Richard using this coded language that I’d heard all my life—that he had been raised “in the household” and “like one of the family.” The white Etheridges treated Richard preferentially while he was enslaved, treatment that other Etheridge slaves did not receive. So, all evidence seemed to point to Richard being related in some way to his formers.

But given the fact that Richard was a slave, it was impossible to truly explore this possibility in the nonfiction book.

For one, there are so few records for slaves. They were property and were treated as property in tax rolls, estate records, and other official documents that you might typically use to do historical research. Consequently, very little information exists about Richard’s life before the Civil War.

Where, in a book of nonfiction, I just could not explore Richard’s family heritage in the way that I wanted to, as fiction, I could. I needed the breadth and scope that a novel offers in order to imagine and explore these relationships fully.

Further, the insular nature of the Outer Banks—where everyone, black and white, is interrelated and in a region that, until fairly recently, was extremely isolated from the mainland South—made it the perfect sort of Petri-dish setting in which to explore the question of race and racial mixing, in the context of slavery.

Q: How did you research the novel, and did you learn anything that especially surprised you?

A: The research for Fire on the Beach was the point of departure for Black Cloud Rising.

Most of the archives and documents I found for Fire on the Beach focused on Etheridge’s life after the end of the Civil War, when he enters the record in a more fulsome way. He was a community leader and, eventually, a recognized Lifesaving Service officer. This gave me a sense of who Richard Etheridge became.

But I needed to figure out how he got there.

At the time I was researching Fire on the Beach, Richard’s passage through the Civil War was largely unknown. The few books and articles in which he appeared didn’t mention it.

Completely by accident, I came upon a letter that Richard had written during the war. I was in the library, researching the United States Colored Troops, broadly, to try to understand more about African American service, and, in flipping through the index of a book by Ira Berlin, The Black Military Experience, I saw his name. There was Richard Etheridge!

It’s a great letter, which he wrote from outside Richmond, during the siege of the Confederate capital, protesting the treatment of former slaves back home in the Outer Banks by the occupying Union army.

The letter gave me an idea of his sensibilities as a young man—and also, very importantly, of his voice. It was incredible. I also now knew his military affiliation. So, I could trace the passage of his company through the war.

The story of the December raid that is the central action of Black Cloud Rising was only a small part of Fire on the Beach—a 10-page chapter, as there was so little information about it, even as it seemed particularly distinctive.

During three weeks, Richard’s regiment—informally called the “African Brigade”—which was led by a white, one-armed, abolitionist zealot not so unlike John Brown, forayed into Northeast North Carolina, where most of the troopers had been enslaved. Their mission was to free the family and friends whom they had left behind in fleeing to join the Union army. It’s a dramatic, awesome story!

I’d stumbled upon it in this small, self-published book by Jerry Witt, Wild in North Carolina: General Edward A. Wild’s December, 1863 Raid into Camden, Pasquotank and Currituck Counties. Witt led me to the New York Times article from the era, by a journalist named Tewksbury.

By the time I returned to the story, for Black Cloud Rising, a few more histories had been written, one about Richard’s unit’s activity during the Civil War, another about the impact of the December raid on that region. Both of those really helped me fill in the details.

The challenge, of course, though, was to make the story read as a story, not as a history lesson. So, I paid a lot of attention to the individual characters. I wanted the reader to be swept up in these characters’ lives.

Most of the characters in Black Cloud Rising, from Edward Wild and Tewksbury to Richard Etheridge and Fields Midgett, were actual historical figures—all but Revere, who I invented from whole cloth, to serve as a foil to Richard.

For some of the real-life characters, I found letters and other documents that, as with Richard Etheridge’s Civil War letter, revealed their voices and, in this way, told me something about their personalities.

Whether I found documentation or not, I tried to imagine the backstories of all of the characters, major and less so, in order to render them as complex, nuanced, willful men and women—characters about whom you would want to know more and with whom you would want to journey along the narrative of the novel.

Q: In a New York Times review of the book, Dwight Garner says, “This is a classic war story told simply and well, its meanings not forced but allowed to bubble up on their own.” What do you think of that description, and how do you think the novel fits into the tradition of war stories?

A: I was so, so flattered by that review. Dwight Garner is a notoriously difficult reviewer, so to get a rave one from him was just great. And then, to have a second review in the Times—by Alida Becker, in the Sunday Book Review—was just so, so great.

(Appearing in the Sunday Book Review has always been a dream of mine. Plus, the illustration in the Becker review is wonderful!)

Garner’s description of Black Cloud Rising makes a certain sense to me. The origins of Black Cloud Rising date back 30 years, from even before Fire on the Beach.

I was living in Paris in my 20s, reading a lot of James Baldwin and Toni Morrison, trying to become a writer, when I saw the movie, Glory. For as ennobling as it was, and brave for its time, I also found myself feeling disappointed and angry as I was leaving the theater.

Though the movie is meant to be about an African American regiment during the Civil War, it’s actually Matthew Broderick’s story rather than that of his black troopers (Morgan Freeman, Denzel Washington, Andre Braugher).

Broderick, the white colonel in charge of the unit, is the focus of the story, the character whose complexity and struggles drive the narrative. I remember wondering what the movie would have been like if one of the black soldiers had been made the central character.

Black Cloud Rising is my attempt to retell that story, only from the African American perspective, by the principal black actor. In that regard, in the same way that Glory is a war story, so too my novel, in recasting and retelling it, is also a war story.

For me, though, this description of Black Cloud Rising, however apt, also always surprises me a little bit. From the beginning, I conceived of it as a story about family. It is my attempt to re-imagine one of our national origin stories, the Civil War tale of “brother against brother”—only this time, one is black, the other white, one the former slave of the other.

When I think about my book, I tend to think of it as a story about complicated family relations across racial lines.

Q: What do you hope readers take away from the book?

A: For me, the American story is about “mixedness”—about the ways in which people of various backgrounds and beliefs have come together, oftentimes despite themselves, to make up our modern racial stew. It was true then, during the era of slavery, and is all the more so now, even as we, as a society, continue to want to deny and resist it.

Above all, though, I hope readers find Black Cloud Rising to be a good, entertaining read.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I’ve spent the past seven months as a Cullman Fellow at the New York Public Library, trying to finish another novel about “mixedness,” this one loosely based upon my parents’ story.

Set in post-World War II Paris, the novel—which is called What Is Hidden Cannot Be Loved—features an unlikely love triangle: a Holocaust survivor, a Sorbonne student from colonial West Africa, and a black GI.

The narrative moves from the 17th-century “Slave Coast” of West Africa to occupied Paris to Civil Rights-era Kansas, and in it, I’m trying to explore the deliberate, as well as unexpected, blurring of cultural, racial, and religious lines that occurs when individuals from communities with very old and very different traditions find themselves pushed together in a world that is in tumult and also desperately in need of renewal.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: Sure, one last thing. As I mentioned, I didn’t want Black Cloud Rising to just be a military story. Every soldier is some mother’s son, some person’s beloved. To that end, three important women characters are central to my novel.

Richard’s mother, Rachel Dough, is one of these characters. She is the source of Richard’s wisdom and also—given the fact of who his father is—of his latent rage. She is as unsparing with Richard, whose fascination with his paternal family is an insult to her, as she is unforgiving of Richard’s father, their owner.

Then, there’s the woman Richard loves and has left behind, in fleeing to join the Union army, Fanny Aydlett. Fanny is also desired by and the target of Richard’s white near-brother, Patrick—though for more base reasons. Patrick merely sees Fanny as an attractive slave who can be, by right, taken whenever he pleases.

She refuses to be a victim, though, and Richard, who, typical for the era, wants to be her Lancelot, finds himself humbled by her ability to take care of herself.

And there’s also Richard’s white half-sister, Sarah Etheridge, with whom, as children, he had developed a friendship. An independent-minded woman in a time that requires that she be subservient to men, she has taught Richard to read, which is illegal, viewing him as a counterpart in shared oppression. But when he runs off in pursuit of his freedom, she suffers it as a betrayal.

Those subplots were really important to me, as I didn’t want Black Cloud Rising to be just a story of men in battle.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment