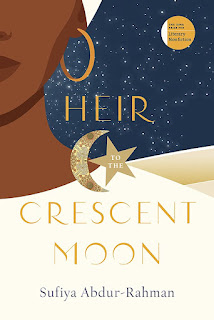

Sufiya Abdur-Rahman is the author of the new book Heir to the Crescent Moon. Her work has appeared in a variety of publications, including The Washington Post and Catapult. She is creative nonfiction editor for Cherry Tree, and she teaches at Washington College. She lives in Annapolis, Maryland.

Q: What inspired you to write Heir to the Crescent Moon?

A: Well, I’m a second-generation black Muslim and I’ve always had a lot of questions about the movement to embrace Islam that my parents and other black people were part of in the early 1970s. I wanted to know what inspired it, what it was like to be part of it, and what happened to it after that point, particularly within families, because each individual Muslim seemed to take such a disparate path with regard to faith.

I set out to find some answers by interviewing other black Muslims around my age and some around my parents’ age. I planned to compile the varying stories and turn it into a book that included my family’s story. I started that project but the more I wrote, the more compelling my own family’s story became.

Eventually, I settled on what is now Heir to the Crescent Moon, which is my take on answering those questions about the post-civil rights black American Muslim movement viewed through the lens of one particular family, mine.

Q: How would you describe your relationship with your father?

A: We’re good. Thanks for asking. But sure, things were a little dicey for a minute, after he first read the manuscript. No parent wants to hear any criticism of them from their child, so you can imagine how fun it would be to have that criticism put in print for strangers to see.

It took a while for my father to understand that what I wrote was coming from a place of love, and even understanding it, it’s still hard to take. But, I’m still his daughter, and he’s still my father and my children’s grandfather. So I would imagine our relationship is similar to that of any adult daughter and father.

There’s a bit of me trying to get him to check emails, him trying to get me to answer the phone, and still lots of packages that he sends me and his grandkids.

Q: The writer Donald Edem Quist said of the book, "It’s a marvel the way Abdur-Rahman blends cultural criticisms and reflections on media into a memoir about the stories we inherit and choose to tell." What do you think of that description, and what do you think the book says about storytelling, especially family stories?

A: I think Donald gets me. As a fellow nonfiction writer—although he writes awesome fiction too—I think he sees all the ways that the various subgenres of nonfiction that I do spill over into whatever I’m writing.

So yes, I’m an arts critic, and yes, I’m a journalist, and yes, I’m a personal essayist, and from my earliest days, I’ve been someone who listened to family stories and have seen them written down, and then began writing my own.

My grandfather—my mother’s father—loved telling stories about growing up in the segregated South. As he got older, he began writing them, really crafting them, and sometimes he would show them to me and ask me to edit them or to give him an opinion on an ending or something, and they were really good.

From him, I learned that moments and people from real life could be as entertaining and fascinating as ones from fiction. I’m fortunate because my grandfather lived to be 95 years old. I had a while to hear and read his family stories and learn about the legacy he was passing onto us younger generations.

I definitely feel it’s important for families to know the legacy they come from, particularly black families from whom so much historical knowledge has not been recorded or has been taken away.

Q: How was the book's title chosen, and what does it signify for you?

A: I wrote that title once I learned what the name of the businesses that my parents’ mosque owned meant. Each of the businesses—a restaurant, a health food store, and a tea room—had Banu-Hilal as part of the name, which translates to “sons of the crescent moon.”

The imam used that name for the businesses, and the congregation, because his ragtag group of Muslims was reminiscent of the nomadic tribe of Bedouins made famous as the subject of epic poetry long after the tribe ceased to exist.

The dispersal of the tribe over the years and the legend they continued to claim reminded me of the sense of admiration for the early days of the mosque that many members I spoke to maintained, regardless of whether or not their own relationship with the mosque continued or dissolved.

I wanted the title to allude to this but couldn’t call myself a “son” of the crescent moon, so I chose “heir.” I hope that makes sense. I think I explain it better in the book!

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I’m trying to whip my next manuscript into shape. It’s an essay collection, focused loosely on the theme of love for black men. It’s mostly personal essays but there’s some criticism in there, some family stories, a lot of taking stock of what it means to be a black woman inextricably linked to black men, for better or worse.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: I really appreciate the opportunity to talk to you about Heir to the Crescent Moon, Deborah! Thank you so much! Feel free to check my website www.sufiya.net for upcoming events and follow me @MrsAbolitionist on Twitter.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment