Kip Robinson Greenthal is the author of the new novel Shoal Water. She worked for many years as a librarian, and now lives on Lopez Island, Washington.

Q: Shoal Water takes place in a fishing village in Nova Scotia. How important is setting to you in your writing?

A: The setting—the fishing village in Nova Scotia—is critical to the story. It’s a place defined by isolation, a “seascape” that literally becomes a character in the book and drives the tone for what happens to the characters.

I’m working on a second book now that takes place in the Pacific Northwest, and the same thing is happening—the landscape is driving the narrative.

Q: What role do you see alcoholism playing in the novel?

A: Alcoholism has an undercurrent role in Shoal Water, its darkest part being the change it can bring to a person’s personality. The tension, the recklessness, the fatal lack of judgment.

I grew up in a house where my parents drank a lot. The mother and father I had in the morning became completely different people in the nighttime after they drank. Somewhere inside me I knew this change was dangerous and could hurt someone. Someone innocent, like a child.

While living in Nova Scotia, hearing the story of a child being killed in a boat accident by a drunken father possessed me. I needed to write a story about this.

As I developed the characters, I wanted to show alcoholism as a scary disease and the pain it can bring to others who are impacted by it. I wanted to reveal the alcoholic character as powerless, or having a total loss of self.

What’s interesting is that, while the accident spurred the story, the fictional outcome became very different. I think this happens when a writer lets the fictionalized characters navigate and take the writer to unexpected places. In essence, the characters become the story, and you the writer are left to journey with them.

Q: You put an initial draft of this novel away for 10 years before returning to it. How did the years away from it change your approach to the book?

A: I think those 10 years gave me the necessary distance to see that my own experience of being an American going to Nova Scotia was central to how the story needed to be told.

At first I didn’t want my main character to be an American going to Canada. I wanted the story to be purely from the Nova Scotian point of view and the earlier drafts contained the stories of those Nova Scotians.

But something was missing. I wasn’t a Nova Scotian and I had a difficult time portraying the interaction between the Americans fleeing the U.S. and the native Nova Scotians embracing or not embracing them.

Once I shifted the point of view to the experience that was authentic to my own—an American going to a small inshore fishing village—the story flowed more easily even though that character, Kate, is still made up.

It’s a strange mix for writers to develop an authentic voice by combining what they emotionally know with something imagined.

When I embarked on my creative journey with these characters, many questions arose in my mind around the accident.

Was the father really drunk at that exact time? Why did he take his young son out on the water when he did? Did the father know the sea was turbulent, or did bad luck bring the onslaught of a rogue wave? What is a rogue wave?

So the accident prompted me to larger questions and took the story in more ambiguous directions.

As a young woman, I experienced being picked up by a rogue wave while I was sitting on a high rocky promontory overlooking the Pacific.

I will never forget the shock of watching the sea pull back and then crest over our heads, picking us up and throwing us back hard into the rocks that bordered the shoreline, our bodies at the mercy of the rogue’s force smashing us down.

When the sea withdrew, we were left torn and bleeding, our bones bruised. The force of the water sucked off my wedding ring as if it had no significance.

Q: What do you hope readers take away from the story?

A: I hope readers take away two things from the story: 1) there’s hope in getting through the darkest of times, and 2) there’s grace in turmoil.

One of the main characters in Shoal Water, Karl, an inshore fisherman, refers to shoal water when he tells Andy about a dream he’s had all his life:

“I'm coming in from fishing, see, but I can't tell west from east, north from south, because the points of my compass don't register. I try to find the markers for the shoals, but the sky's as black as the sea, and I can't see nothing. I know the shoals are coming like a man can smell the warmth of another human being when his eyes are closed. But the difference is my eyes are wide open. The boat pitches beneath me and I know I’ve come in by the shoal water. Fear, that's what I call the shoal water, fear that you run aground and let the sea break over you.

Shoal water is the fear inside me. Yet if I can feel the shallows coming in time, I can right myself and get through them.”

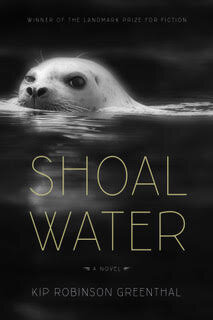

Secondly, grace is represented by the seal in the story. Whenever a seal appears in time of danger, it gives back life to those who experience it, and to those who believe it. Magical realism has a role here, asking the reader to believe in the possibility of transformation.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I have been writing stories over the last 20 years about my experience of being the mother of two daughters who were sexually abused by their father.

I was married to their father for 12 years, and left him when my daughters were 7 and 9. My youngest daughter told me about the sexual abuse when she was 14, long after we had been divorced. My world blew apart then, and my sense of reality deeply shattered.

To make a long story short, after my daughters and I were in therapy, her father was diagnosed as sociopathic. He is no longer in our lives.

This experience has sent me on a long journey of trying to understand family violence and mental illness. It has also sent me on a journey to look at myself, and try to discover why I was blind to what was happening to my daughters.

My ex-husband was physically abusive towards me, and my daughters witnessed some excruciating scenes. While I looked for his physical violence towards my daughters, sexual abuse never occurred to me. My daughters had been trained not to reveal anything or tell me about it.

This was in the ‘70s and very little was known then about domestic violence or sexual abuse.

After my mother’s death in 2001, I thought more openly about my own childhood to try to find clues for why I was drawn to marry a man who was mentally ill.

My mother was mentally ill and suffered from psychotic breaks. She also was physically abusive towards me. And I saw it—the pattern of abuse passed down from one generation to another.

There’s practically nothing written from the mother’s point of dealing with the sexual abuse of her daughters. Because I am a fiction writer, I have begun writing short pieces and poetry on this subject, using my own experience but fictionalizing it.

“Auto-fiction” is a new term for combining fiction with memoir, so I think this is what I am aiming for in my second book.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: I now live on Lopez Island in the Pacific Northwest, where I’ve lived off and on ever since I was a child. My family bought property there in 1959, and it’s always been my spiritual home.

I met my present husband, Stanley Greenthal, on Lopez in 1987, and we are very happily married. Stanley is a musician, who wrote the music for the song "Shoal Water," and we shared in writing the lyrics.

This song was recorded on his album, All Roads, and a recent re-interpretation of the song on Solstice Fire, with our group, SeaMuse, in 2019. Singing this song together over the years helped me believe that someday my novel Shoal Water would be published.

My favorite activities are playing the drum, the bowed psaltery, and singing with our SeaMuse band. I also enjoy walking and gardening, where I can let my mind and imagination roam and meditate.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment