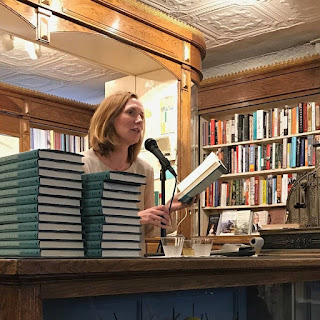

Bethany Ball is the author of the new novel The Pessimists. She also has written the novel What To Do About the Solomons, and her work has appeared in a variety of publications, including Electric Literature and Literary Hub. She lives in New York.

Q: What inspired you to write The Pessimists, and how did you create your three families?

A: I love small, enclosed communities to explore and to write about.

I started out with a few of the characters: Rachel, who was a transplant from the city and dealing with not quite fitting in to the community or the school, and Virginia, who was dealing with a cancer diagnosis and the loss of love in her marriage, and Tripp, who was dealing with loss of income and paranoia over the state of the world.

Their spouses came later. I really enjoyed fitting them together—what character went with who.

Gunter was a lot of fun to write. I love that he’s married to Rachel, who cares so much what people think. He’s really loose and sure of himself and blurts out whatever is in his head. He’s picked up on the high status of Scandinavian countries in certain American circles. He both plays up to and likes to contradict those stereotypes.

Q: The novel centers in part around a private school called the Petra School. What inspired your creation of this school and its headmistress, Agnes?

A: I attended a progressive program within the public school. It was created so that liberal white parents would send their children to the lone Black school in our community and thus skirt around Brown vs. Board of Education.

I loved the school, my teachers, and my classmates, but that sort of education wasn’t good for me. I would have done much better in a more structured setting. All I did was read books—no matter what it was I was supposed to be studying. My kids often wonder what in the world I learned in school since I can barely help them with homework.

I started out writing The Pessimists with a school that didn’t teach its students much (to be fair, OTHER kids I went to school with learned plenty!).

I was also interested in exploring how small communities can become cult-like. America is ripe territory for cults because it’s so vast, our communities are dispersed, people live far away from their extended families, move away from their hometowns. People like to belong to something. I think it’s hardwired in our DNA.

And parenting is a time of huge uncertainty for so many of us. We want to do differently from our parents, or maybe we want to be exactly the same parent as our own parents were to us but our children are completely different.

I felt terribly uncertain about myself as a parent with my first child and also kind of furious at the culture I found myself in: with little help, little money, no community. I couldn’t believe parents were expected to make play dates for 9- and 10-year-olds.

After the birth of my first child 18 years ago, I had no awareness of how drastically the world had changed since I was a kid. I think it’s a huge loss for children to be so fearful of their neighborhoods and stuck inside glued to their screens.

And it’s a huge loss for mothers who are expected to watch over and/or entertain their children every minute of the day. If that’s what they want to do, that’s wonderful, but for many of us there is no choice. That pressure, to me, felt insurmountable.

Add to that ideas like “attachment parenting” or “simplicity parenting” and it feels like our society is trying to pull women backwards, into the house surrounded by children night and day and out of the workforce. Writers like Lenore Skenazy and Kim Brooks talk about these issues quite a lot.

Q: How was the book's title chosen, and what does it signify for you?

A: My character Tripp is the ultimate pessimist. He has absolutely zero belief in the system. He has lost quite a bit of income in the 2008 recession and feels the walls closing in on him. He globalizes his losses, and gets sucked into a group of men who believe the end of the world is nigh—the ultimate pessimistic credo.

Q: The Kirkus Review of the book says, "Despite Ball’s mordant humor, the pain here feels all too real." What did you see as the right blend between humor and pain as you wrote the novel?

A: I don’t find books without humor to be especially realistic. There is almost always humor somewhere, at least in the world I live in. My mother’s humor was mordant to the extreme and I guess I probably inherited it.

I discovered recently that my mother’s grandmother accidentally shot my mother’s grandfather through a screen door, killing him. They were sharecroppers in Oklahoma and my mother’s mother, my grandmother, was about 12 when it happened. It took him six hours to die and he died at home.

I mean, it’s a fact of my history I’d always known about, but my mother told the story with a kind of grim laugh, almost as though it was funny or a punchline.

I’m sure this was a coping mechanism used as a way my mother’s family could acknowledge that awful reality without getting swept up in the absolute horror of it. But I couldn’t feel how painful it must have been until I read the newspaper stories of the time.

Perhaps humor was my mother’s people’s therapy. A way of getting on with things when there’s no time, money, or energy to really process tragedy or trauma.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I’m working on two novels at the moment.

The first is a novel about a city in Detroit. At a certain point I became obsessed with a factory close to where I grew up. There were three superfund sites in an area less than three square miles. But I’ve been trying to write that particular novel for five years now and in fact threw it over for The Pessimists.

The second novel I’m working on is set in New York City just before Y2K. It involves a young girl who’s just arrived in the city, and finds herself homeless, and an older magazine editor who is about to find himself on the cover of New York magazine for accusations of sexual harassment.

The second novel is frankly much more fun to write and I imagine that’s the one I’ll finish first.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb. Here's a previous Q&A with Bethany Ball.

No comments:

Post a Comment