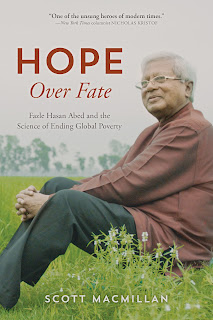

Scott MacMillan is the author of the new book Hope Over Fate: Fazle Hasan Abed and the Science of Ending Global Poverty. It focuses on the life of the founder of the antipoverty organization BRAC. MacMillan is the director of learning and innovation at BRAC USA, and he lives in Connecticut.

Q: Why did you decide to write about Fazle Hasan Abed (1936-2019)?

A: A little more than a decade ago, I was a freelance journalist who had caught the “development bug”—a curiosity about successful (and unsuccessful) approaches to lifting people out of poverty.

I was traveling overland in Africa, supporting myself with travel writing gigs, when I learned about an organization called BRAC, based in Bangladesh, that had recently started working in a few African countries, doing a combination of microfinance, women’s healthcare, education and various other programs.

Unlike so many other failed development ventures, BRAC (formerly Bangladesh Rural Assistance Committee) was known for being efficient and effective. It seemed to have a reputation for “development done right,” and was credited with having transformed Bangladesh. Its founder, Sir Fazle Hasan Abed, had recently been knighted by the British crown for his services to humanity.

I applied for a job and somehow got it, despite not having much previous experience in nonprofit work.

Over the next several years, I developed a rapport with Abed, and ended up working as his speechwriter. Despite his knighthood, he was a soft-spoken man who wasn't very good at marketing himself—the opposite of the many self-promoters who make a name for themselves in the nonprofit field. And yet he was incredibly well respected in the international development sector.

He also had an amazing story that had never really been told before—in part because he really didn’t like telling stories about himself—and I thought someone needed to capture that and share it with the world. That someone ended up being me.

Abed was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer in 2019 and died within months, but not before encouraging me to finally finish this book. He was able to read most of it on his deathbed.

Q: How was the book's title chosen, and what does it signify for you?

A: I struggled with the title, just as so many people have struggled to capture in a few words what BRAC is really “about,” since it works in so many different areas.

But after spending many, many hours talking to Abed and piecing together his story, I realized there was a theme that united his life's work, going back to the early 1970s. This was the idea that people often remained poor in part because they believed it was their fate to be poor, and if you gave them a reason to believe the future could be better—that is, if you gave them hope—this itself had the power to help them overcome poverty.

This theory is potentially misleading, even dangerous if misunderstood, since it risks creating the impression that poverty is somehow self-inflicted, and that if you're poor, all you really need is a good pep talk. This is plainly not the case. Hope itself doesn’t buy you a loaf of bread. But it has to be part of the solution, and it does seem to explain why so many poverty programs fail.

For those caught in the trap of extreme poverty, most poverty programs—skills training, healthcare, goats and chickens, cash transfers, microloans, and so on—are likely to fail if they don’t address some of the underlying psychological aspects of poverty, including a deep-rooted sense of despair.

Abed saw that things start to change when people believed in themselves and their ability to create change around them, when they had good reason to believe that their hard work could really make a different in their lives.

Providing essential services and opportunities is essential, but so is giving people hope. This may sound soft and airy-fairy, but hard economic research now supports this idea. Abed called it “the science of hope.”

Q: As his speechwriter, what was it like to work with him, and did you need to do much additional research to write the book?

A: Getting Abed to tell stories was often like trying to wring water from a stone. Even though he loved poetry and could recite Shakespeare's soliloquies and long passages of T.S. Eliot, he was an accountant at heart, and he believed numbers told stories.

He could recite statistics about maternal mortality rates, but he had difficulty bringing them to life with actual names and faces. There’s an irony there, because his first wife actually died in childbirth—and it took to me ages to get him to tell that story, in all its awful detail.

In addition to talking to Abed, to supplement the research I had to spend countless hours digging up old project reports—yellowed, photocopied pages from 40 to 50 years ago—and poring through them to look for nuggets that I might use to piece together the story of BRAC.

I also interviewed at least 50 different people, including his friends, family, co-workers, and former co-workers—even some who split with Abed on bitter terms.

Q: What do you see as his legacy today?

A: Abed would have said (in fact, he did say) that BRAC itself is his legacy. With 100,000 employees serving about 100 million people in about a dozen countries in Asia and Africa, it is, by many measures, the world's largest nongovernmental organization. This is why the book’s jacket makes the bold statement that Abed may well be the most influential man that most people have never of.

I believe his legacy goes well beyond BRAC, however. On Abed’s 80th birthday, Bill Clinton told him that “you've revolutionized the way we all think about development.” Even though he avoided the limelight, many of his methods changed the way global policymakers think about poverty.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I am the director of learning and innovation for BRAC USA, the U.S. affiliate of BRAC. As part of that work, I oversee a portfolio of research grants that help BRAC learn from its mistakes. Abed believed strongly that BRAC should be a learning organization—never wedded to an ideology or methodology, but relentlessly focused on what finding out works, through iteration and research.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: There's a passage from an article—one of the last ones that Abed and I worked on together before he died—that I believe captures what “hope over fate” really means. Asking policymakers to invest in “hope” is not some vague, soft-hearted appeal, argued Abed.

“For too long, people thought poverty was something ordained by a higher power, as immutable as the sun and the moon,” he wrote. “This is a myth. We would do well to start paying attention to the evidence, which says that giving people hope and self-esteem may be the greatest investment in human capital that any country can make.”

For Abed, the ability to break free of this myth was one of the essential characteristics of being human.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment