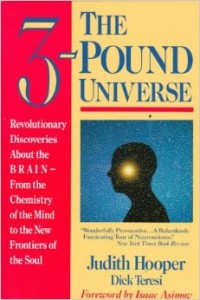

Judith Hooper is the author of the new novel Alice in Bed. It focuses on the life of the writer Alice James, who was part of a literary family that included her brothers Henry James and William James. Hooper's other books include Of Moths and Men and The Three-Pound Universe. Her work has appeared in a variety of publications, including The Atlantic and The New York Times, and she lives in western Massachusetts.

Q:

Why did you decide to write a novel about Alice James?

A:

It happened when I was researching a nonfiction book centered in late 19th century

Boston that was refusing to come together. I fell mysteriously ill (not unlike

Alice James) and while stopped dead in my tracks, I found myself unexpectedly switching

gears to fiction.

William

James had been part of my stalled book and I was drawn to the diary and letters

of his “hysterical” sister. Alice was droll, original, and somehow startlingly

modern; she didn’t suffer fools gladly and painted hilarious word-portraits of

her world (referring to Britain’s “tinsel monarchy” and observing, “How they

must love to see a back!”)

Perhaps

because she herself had suffered, she empathized with the English poor, the Irish,

and colonized people everywhere. She’d have made a great heroine even if she

hadn’t had two famous brothers and written a diary that stunned the literary

world.

As

a devotee of Proust, I was drawn to this person with a vivid inner life and

almost no outer life. But how to write it? My solution—which did not emerge

immediately-- was to start with Alice in bed, in England, in 1887, and travel

back in time as she relives (or re-dreams) her life.

Q:

How did you research the book, and what did you see as the right blend of the

fictional and the historical in creating the novel?

A:

I think it is a personal choice dictated partly by the research material

available. I tried to make a world that was true, believable, and three-dimensional,

without anachronisms. (An example of a near-anachronism: In writing a scene

with Alice and Henry in Montmartre, it was only luck that I discovered that the

basilica of Sacre Coeur had not been built in 1875. Glad I checked.)

About

75 percent of Alice in Bed is factually true; and the other 25 percent is, I

like to think, plausible. Like many people of the era, the Jameses burned many

of their letters, and I like to imagine that the scenes I invented were

channeled from the letters that went up in smoke.

I

read everything Alice James wrote, which is to say, her letters and her diary.

I combed through hundreds of James family letters; studied Henry’s novels,

travel diaries, journals, and autobiographical writing, William’s letters, journals,

psychological papers, and forays into the occult. (He was fascinated with

psychics and famous for hypnotizing guests at Beacon Street dinner parties.)

I

read histories of Harvard; late 19th medical tracts, steamship narratives and

railroad timetables. I wanted to know how people talked, what words they used;

how many trunks they took when they sailed to Europe and what the hotels were

like.

As

I was interested primarily in recreating the world of women, I researched

clothing and hairstyles as well as the sort of helpful advice dispensed to

women in magazines such as Godey’s Lady’s Book.

The

19th century was a great age for friendship and of letters. Our age seems

impoverished by contrast.

Q:

How did you pick the book's title, and what does it signify for you?

A:

At first I wanted to call it “Arm Yourself Against My Dawn,” an excerpt from a

letter Alice wrote to her brother William. The rest of the quote was, which

shall cast you and Harry into obscurity. It is so deliciously Alice; she is

joking but there is a hard core of truth in it.

But

I could never remember the title exactly, so I decided on “Alice in Bed,” although

it had already been the title of a play by Susan Sontag and a novel by Cathleen

Schine.

It’s

a play on words, obviously; Alice’s bed is her sickbed; but it is also the bed

she shares with her lovers, Sara Sedgwick and Katherine Loring, and the place

where she dreams her life.

Q:

The novel jumps around chronologically--did you plan the structure before you

started writing, or did it develop as you went along?

A:

It developed slowly; I actually rewrote the novel three times. Alice’s mind is

astonishingly creative, but at some point we need her to get up and do things.

So

the novel starts in 1887, with Alice, age 38, living in rented rooms in

Leamington, in the English Midlands, with a hired nurse. That part consists of

five short chapters.

In

Part II, we travel back to her youth in Cambridge, Massachusetts. That section

begins with her youthful lesbian love affair, at age 18, and ends in 1878, when

William marries and (not coincidentally) Alice suffers her most serious nervous

breakdown.

In

Parts III and IV we are back with Alice in Leamington. from 1887 until 1893.

But through Alice’s memories and daydreams, we keep delving into the past,

tunneling ever closer to the events and circumstances that formed Alice James.

Q:

Much of the novel deals with the relationships among Alice and her brothers,

including Henry James and William James. What was Alice's role within the James

family, and what does her story say about the role of women during her

lifetime?

A:

Alice was the youngest child and only girl in a brilliant family that was also

haunted by mental illness. She adored her four brothers, and they her, but as a

female her fate was fixed and her choices limited (marriage or being “a comfort”

to her elderly parents).

Marriage

did not tempt Alice, and, unlike her busy, practical mother, she was bored by

housekeeping. She was equally ill-suited to the occupations open to upper-class

Boston females--doing charity work and serving on committees. She was born 10

years too soon to go to college (and her father considered colleges “hothouses

of corruption” in any case).

She

had a brief fling with Boston’s Society to Encourage Studies at Home, becoming

a history teacher in a mail-order educational program for women living in cities

and towns lacking libraries. As her health unraveled, this did not last,

either, though it did introduce her to Katherine Peabody Loring, with whom she

entered into a lifelong “Boston Marriage.”

Like

her brother Henry, Alice was an introvert and an intellectual; she was

fascinated with history and politics, read serious books, and subscribed to 30

or 40 newspapers, magazines, and journals while living in England.

She

was a born writer—with the Jamesian subtlety joined to a more direct prose style

and more subversive social and political attitudes. But female literary

ambitions were not encouraged. A woman’s place was in the home and exposing oneself

to the public, even having one’s name in the newspaper, was considered very

poor taste, an embarrassment to one’s family as well as oneself.

Fortunately,

as sometimes happens, illness and misfortune drove Alice deeper into herself

and unlocked her muse.

If

you noticed a hint of incest in Alice in Bed, you are not mistaken. In the 19th

century, when girls were kept from mingling too much with the world, brothers

and sisters and cousins frequently formed close, quasi-erotic bonds.

Alice’s

father, the mercurial Henry James Senior, had a flirtatious relationship with

her, and William often played her courtly lover, writing Alice romantic sonnets

and love letters from abroad. Her relationship with Henry was less flirtatious

but very deep, and was most likely the model for the psychically enmeshed

brother/sister pair in The Turn of the Screw.

The

four James brothers were all enamored of their cousins, the five Temple girls.

Minny Temple, who died in her early 20s, was the template for several of

Henry’s heroines, including Isabel Archer of The Portrait and the tubercular

Milly Theale of The Wings of the Dove.

There

are hints here and there that William at one time proposed marriage to Minny

Temple, and this is explored in Alice in Bed. There is also a strange episode

involving Minny’s elder brother, the sociopathic Bob Temple, and 13-year-old Alice.

But I don’t want to give too much away.

Q:

What are you working on now?

A:

I’m working on a novel, set in the present or recent past, tentatively entitled

How to Disappear and Never be Found. The main characters are three teenage girls

from a performing arts high school who make a suicide pact. (It is not a YA

novel.)

Q:

Anything else we should know?

A:

What drew me to Alice James and her brothers was their idiosyncratic family

culture. Thanks to their father’s distrust of schools, they were educated

privately, largely in Europe.

Thus

the five siblings—William, Henry, Wilky, Bob, and Alice-- grew up like an

isolated tribe on an island, with their own language and customs. (They all spoke

fluent French.)

I

found it intoxicating to be in this world, to sit around the James dinner table

in Boston in 1875, listening to the jokes and bons mots fly. I hope my readers

will have the same experience.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

No comments:

Post a Comment