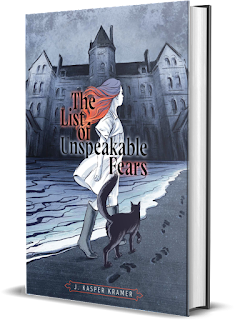

J. Kasper Kramer is the author of The List of Unspeakable Fears, a new middle grade historical novel for kids. She also has written the middle grade novel The Story That Cannot Be Told. She is an English professor in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Q: In your new book's Author's Note, you write, "To say the COVID-19 pandemic changed The List of Unspeakable Fears is an understatement." Can you say more about that, and about what it was like to write a book dealing with anxiety and contagious diseases during a pandemic?

A: Like Essie, I have an anxiety disorder. Though I’m not frightened of everything the way she is, I deal with a lot of catastrophic thinking and excessive worrying. The pandemic exacerbated all of that for me, as I’m sure it did for everyone who struggles with mental health.

Writing even the most cheerful novel under those circumstances would have been difficult, simply because of the pressure that comes from having a book on deadline. Writing this novel in particular was by far one of the most challenging things I’ve ever done.

For those who haven’t read my Author’s Note in The List of Unspeakable Fears, I feel like it’s important to clarify that this book sold to S&S/Atheneum right before the pandemic started.

It wasn’t totally finished at that time, but a lot was already written, and the plot as a whole was completely outlined. This means it was a complete coincidence that I had to finish drafting and revise a novel dealing with epidemics of the past during the start of our own pandemic.

On the surface, I suppose this seems like a positive thing, since it makes my book more relevant. But the truth is, it was really hard for me. The number of similarities between life during the epidemics of the early 1900s and life during COVID-19 are shocking.

From overcrowded hospitals and the distrust of vaccines to asymptomatic carriers and questions about personal rights vs. public health, the same controversial topics headlining the news in 2020 were headlining the news in 1910.

Sometimes it felt impossible to get away from it all. When my research or writing brought me to a dark or stressful place, closing my laptop didn’t do much to help, since I’d then have to deal with the eerily similar (and equally tough) things going on in the real world.

However, those same difficulties shaped the book into something more real and more important, I think.

I leaned into Essie’s anxiety disorder. I leaned into her grief and her growing determination to find her bravery. It felt incredibly important for me to finish the novel.

I believed (and still believe) that children (and adults!) with anxiety disorders need to see themselves represented in books in a way that paints them as strong, resilient, and capable.

I wanted Essie to be out there on shelves because I wanted people to see a character go through something as difficult as we all have and still find hope and light and happiness in the end.

Q: Why did you decide to set the novel on New York's North Brother Island, and did you learn anything surprising in the course of your research?

A: You might laugh, but my interest in North Brother Island came from a Buzzfeed article that someone shared on social media! The article led me down a rabbit hole of research into the creepy history of the place, and I knew instantly that I had to set a book there.

It was much later (a couple years even?) that a real family heirloom with a tragic past inspired the actual plot of my novel. Brainstorming with my husband—my go-to partner for story help—led to those two ideas blending. It only seemed natural that North Brother Island would be the right fit for a ghost story.

I did so much research after that. I even spent a week in New York City, visiting museums, walking the streets around Essie’s home, and going through archives in the public library.

It was through research that I learned so much about Mary Mallon and the General Slocum, and those key pieces solidified that the book would be set in 1910.

As for a surprising research tidbit, did you know many of the islands in the East River were expanded with literal garbage? This practice was actually pretty common (and is still sometimes used), but I hadn’t heard of it before, so it was a wild discovery for me.

Q: What did you see as the right blend of fiction and history as you wrote the book?

A: For me, the right blend is always a blend that favors the story.

Don’t get me wrong. I love history. I minored in history in college. I get giddy when I have to use microfilm and little brings me more joy than a library trip that results in a bag of fat history texts with long, tedious titles.

When I’m doing research for a specific story, I always far, far over-research, because it’s hard to stop myself. There’s always one more thing to look into. One more lead to follow.

I suppose this is because I never know which door will reveal some important piece of my story that I don’t yet know I need. When this happens for me, it’s like magic, so I can’t resist it!

However, the danger that writers face—especially us historical fiction writers—is that overloading your novel with all the research you’ve done is a fast way to weigh it down and make it boring.

So when I say that the right blend of history and fiction is the blend that favors the story, what I mean is that though I compile hundreds of pages of research for any given book I’m working on, only a very small percentage of that actually makes its way onto the page, because I only include historical information that will develop character, setting, theme, or move the plot forward.

As an example, the tragedy of the General Slocum became an important part of some characters’ backstories in The List of Unspeakable Fears.

And while I didn’t use anywhere near all the historical research I gathered on this topic, there’s an entire chapter in the book dedicated to describing this event. This is because, in this case, the history is integral to readers understanding important characters—it’s integral to the actual story.

On the other hand, I did about a week’s worth of research on oysters for this book. (They were really important in New York City once upon a time!) But that resulted in a grand total of about three sentences worth of content in the final draft. Oysters wound up not being integral to the story, so they mostly got filtered out.

Q: What do you hope readers take away from the story?

A: I hope readers find some comfort in knowing that we’ve been where we are now before. This has been a difficult couple of years, but for me, knowing that our country (and our world as a whole) has battled illness and hardship like this in the past encourages me. It helps me feel confident that we can thrive again. That there’s hope.

I suppose, most of all, that’s what I really want readers to take away. Hope. The List of Unspeakable Fears is a book about grief and anxiety and fear, yes—but the little girl at its heart overcomes these things. (That’s no spoiler, either, because I will never write a children’s book without hope at the end.)

Essie finds her bravery. I want readers to find theirs, too.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I always love this question! I’ve got a young adult novel in revisions. It’s a historical fantasy (with a touch of romance!) set in 1850s Poland. The story incorporates a ton of dark, strange folklore from the region—changelings and forest giants and water nymphs and curses—and I’m so in love with it!

The new middle grade book I’m working on is another historical fiction. This one takes place in 1970s Appalachia in a rural mountain holler.

When a group from the Church of God with Signs Following sets up a revival tent in her community, young Delilah is at first intrigued by their practice of handling poisonous snakes during services.

However, when her older sister Eve chooses to participate in the snake handling, Delilah becomes terrified she will be bitten and decides she must stop her.

Like all my novels, folklore plays a big role in the story. There’s hill magic, local myths, and tons of rural traditions. Appalachia is a treasure trove for folklore!

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: Some exciting things have happened with my debut middle grade novel, The Story That Cannot Be Told, since I last appeared on the blog!

Since then, the book has made its way abroad, getting translations in Germany, Iraq, and—just recently—Russia! I’ve absolutely adored getting to see the new covers and watching as Ileana travels around the world. She would love that so much.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb. Here's a previous Q&A with J. Kasper Kramer.

No comments:

Post a Comment