ON THIS DAY IN HISTORY

Nov. 30, 1835: Author Mark Twain born.

POSTING Q&As WITH AUTHORS AND ILLUSTRATORS SINCE 2012! Check back often for new Q&As, and for daily historical factoids about books. On Facebook at www.facebook.com/deborahkalbbooks. Follow me on Instagram @deborahskalb.

Saturday, November 30, 2013

Friday, November 29, 2013

Thursday, November 28, 2013

Q&A with author Katherine Harmon Courage

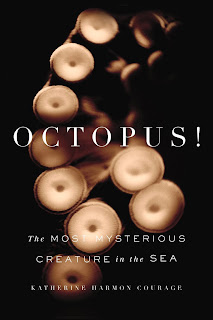

Katherine Harmon Courage is the author of the new book Octopus!: The Most Mysterious Creature in the Sea. She is a contributing editor for Scientific American, and she lives in Colorado.

Q: What is it about the octopus that is so fascinating to

many people, and why did you decide to write this book?

The octopus is one of the strangest, most alluring animals.

If you saw one walking around on land in a Sci-Fi movie, you would think

"yeah, right." But here it is, right here on Earth. They just hide

well underneath the waves, so we have been slow to recognize them as such

incredible animals.

They have been a part of culture--culinary, art,

mythology--for thousands of years. But recently they have also been teaching us

some incredible things about science. For instance, they can camouflage using

color, light, and texture; but, from what we know, they are color blind. And

other than color vision, our eyes and their eyes have evolved to be almost

identical, despite our last common ancestor being a sightless sea worm that

lived at least 500 million years ago.

What finally drew me in and convinced me that I had to write

a book about the octopus was a recent study that showed that octopuses can

actually use tools. These squishy invertebrates were collecting coconut shell

halves in the wild and using them to make shelters when they felt threatened.

Needless to say, they have a lot to teach us about the emergence of

intelligence--in addition to other fields of science.

Q: What was the most surprising thing you learned in the course of researching your book?

Aside from their incredible (and mysterious) camouflaging

abilities and their stunning intelligence, I was very much struck by their

suckers. Each octopus usually has more than a thousand individual suckers, and

each one can be controlled individually. Perched on top of a movable stalk, a

sucker can rotate, open, pinch, and, of course, form a powerful seal. They can

also "taste" the water around them via chemosensors (imagine if you

could taste that apple slice you were holding!).

Individual suckers can also coordinate with one another.

Biologists I spoke with observed octopuses passing small objects up and down

their arms using only their suckers. They nicknamed this move the

"conveyer belt."

Q: You write about the intelligence of octopuses, as well as their tendency not to be social, and you state, "The octopus's dearth of these prosocial behaviors puts it at a considerable disadvantage for gaining easy esteem from humans." How have those two characteristics--intelligence and solitude--affected the octopus and scientists' ability to study them?

A: The octopus is obviously very different from the many

other "intelligent" animals we study--dolphins, dogs, chimpanzees,

whales, elephants. Not only are those animals all mammals and vertebrates, they

are also all extremely social. In fact, so much of what we think we know about

their intelligence comes from observing their social interactions: whales

talking to one another, dogs figuring out the group pecking order via play,

chimps teaching other chimps how to use tools.

But once all of this so easily recognizable (to us, at

least) complex behavior is off the table, as it is with the solitary (and often

cannibalistic) octopus, we are left looking more carefully for other behavioral

clues about intelligence. Although this is of course more difficult, it is also

good for science. It forces us to get out of our own social, mammal, vertebrate

heads and try to put ourselves more in the mind of the octopus. A fantastic and

refreshing challenge!

Q: Did you have a favorite among the locations you visited

to research the octopus?

A: I loved my time in the small Greek fishing village of

Gythio. The restaurants there along the harbor string the day's catch of

octopus above their front doors. Hardly anyone in the town spoke English, and

my Greek was even skimpier. But when I was able to strike up a basic

conversation, everyone was perplexed about why I would write a book about the

octopus. It had been such a common, simple staple, so integrated into daily

life for so many generations that an entire book dedicated to the octopus

seemed almost as mysterious as I found the animal itself to be. This deep

connection with the octopus was enchanting to me.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I am still a contributing editor for Scientific

American magazine (where I keep the blog Octopus Chronicles) and have been writing

for WIRED, Popular Science, Gourmet and others, which keeps me plenty

busy. But I have been enthralled by research going on right now into the human

microbiota (the microbes that live in and on us that are turning out to be so

important for our health). I am also harboring a secret fascination with

fungus. I hope to be able to explore both more soon.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: Well, octopus was actually an odd topic for me to tackle.

I grew up in landlocked Oklahoma and detested seafood for the first half of my

life. I certainly didn't meet an octopus until I was an adult. But in a way, I

think this perspective was an asset when researching and writing the book. I

was truly discovering the octopus as I went. Although, I had only nine months

to research and write the book--on top of a full-time job--so I guess you could

say I had to dive into the deep end. But I was lucky to have such a compelling

swimming companion. I still just cannot learn enough about the endlessly

amazing octopus.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

Wednesday, November 27, 2013

Q&A with Professor Deborah Jordan Brooks

Deborah Jordan Brooks is the author of He Runs, She Runs: Why Gender Stereotypes Do Not Harm Women Candidates. She is an associate professor of government at Dartmouth College.

Q: Your book challenges the idea that gender stereotypes are

harmful to women candidates. Why has that idea become entrenched, and why do

you disagree with it?

A: I suspect that a major reason that the conventional

wisdom persists is that people observe gender dynamics in their workplaces and

in their social lives, and they may see a fair number of situations where

potentially powerful women seem to have some kind of disadvantage. It

might seem logical to think that similar dynamics would exist in politics.

For example, anecdotes abound – and academic research

generally supports – the idea that women business leaders, especially women in

male-dominated industries, have to be tough to be taken seriously; however,

when they act tough, women are the more likely to be disliked. It doesn’t

seem like much of leap to assume that women might face a similar double bind in

politics.

But business leaders are generally expected to perform very

different functions than politicians, and they also tend to be much closer to

their evaluators in a manner that might make people’s expectations more

gendered.

After all, you might expect something different out of a boss

you will see every day and who will be evaluating you, versus a politician you

are unlikely to ever even meet. To the extent that powerful women may be

at a disadvantage in the business world and/or social life, I just do not find

any evidence that it is occurring in politics.

There are other reasons, too, that the conventional wisdom

exists. For one thing, it is possible that women candidates were actually

at a disadvantage in politics in the not-so-distant past, and people haven’t

updated their beliefs on that in the more recent era.

But another thing to keep an eye on is that there may be

some political players who have a financial interest in promoting the idea that

women are at a disadvantage.

After all, a woman candidate who is told she

needs extra help because she is at a disadvantage may spend more on some of the

services that political consultants can provide; moreover, potential campaign

donors who are told that women candidates are at a disadvantage may potentially

be more willing to open their wallets for particular candidates or political

causes.

As academic evidence mounts with findings that the public is

quite equitable towards male and female candidates, it may be quite interesting

to watch who is most vocal about insisting that it is not the case, and the

basis on which they are making those claims.

Q: You write, "Many potential women candidates believe

that they need better qualifications than men to have a chance at winning a

campaign. This study shows that those perceptions are quite clearly

wrong." What does your study show instead?

Research by others has found that potential women candidates

cling to the idea that women have to be better than men – “twice as good” is a

common mantra – to win elections. And political commentators often perpetuate

this belief, arguing that a male candidate would not be questioned for

something (lack of credentials, lack of experience, etc.) that is perceived as

a weakness for a woman candidate. If true, that could have been a big

problem for women in politics.

Yet my research shows that male candidates suffer somewhat

more from political inexperience in a few specific ways than women

candidates. It was one of the very few instances in my entire study where

I found that the public was harder on candidates of one gender than on the

other, and it was exactly counter to conventional expectations (more precisely,

people were not more or less likely to support the inexperienced woman

candidate overall, but they rated the woman more highly on some specific characteristics).

Looking beneath the surface, it turns out that people are

viewing the inexperienced woman as an outsider, and giving her some positive

credit for that, with relatively higher ratings for the woman on

characteristics like “Honest,” and “Will improve things in Washington.”

The inexperienced male candidate does not get that “outsider bump,” perhaps

because he is assumed to be similar to the bulk of politicians already in

office.

The bottom line is that this shows we cannot explain the

dearth of women in office by saying that it is because they have to be better

than men to win. There is no evidence that is true.

Q: One of your chapters deals with candidates crying or

displaying anger. How do those behaviors affect attitudes toward both male and

female politicians, and does it differ?

A: My results are unequivocal that candidates should do

everything they can to avoid angry outbursts while on the campaign trail.

That is not surprising. What is interesting is that, despite ample

speculation to the contrary by the media and others, it is no worse for a woman

candidate to blow her top than a man. They will both be equally in

trouble with the public if they cannot contain their anger.

The act of crying is more interesting because it involves

more nuanced dynamics. Many readers will recall the flurry of media

speculation at the time of Hillary Clinton’s “emotional moment” on the day

before the 2008 New Hampshire primary. At the time, many pundits

speculated that women cannot cry on the campaign trail without losing public

support.

But, despite the footage of her misty-eyed discussion with a

group of women voters, Clinton went on to a surprise victory in the New

Hampshire primary. Many wondered if there was a connection, even though

it was counter to the conventional wisdom: women politicians should not show

emotion or they will get penalized for it far more than men.

My results do not suggest that women politicians fare any

differently than men with the public when they cry, and that crying only has a

fairly modest depressive effect overall on public opinion anyway. But

that does not mean that Clinton did not benefit to some extent from that

incident. Crying tends to take a toll on the attributes that Clinton had

already hit home with voters (strong leadership, ability to handle an

international crisis, etc.), and it can actually help candidates with the particular

dimensions on which she was having the most trouble (honesty, compassion,

caring, etc.).

As such, Clinton’s “emotional moment” may have improved the

public’s views of her, but it would not have been because she was a

woman. It was because tears seem to be able to help tough candidates

connect with voters at an emotional level, regardless of whether the candidate

is a man or a woman.

Q: What do you see as the outlook for women candidates?

A: For any given woman who chooses to run for office, my

research would suggest that she will do at least as well as a comparable man in

winning over the public. So the outlook, at least among those who run, is

good. Gender will not hold a woman back from successfully wooing the

populace.

If it is not discrimination by the public, why aren’t there

more women in office, then? And why haven’t we had a woman president yet?

Based on the research to date, common alternative

explanations do not seem to pencil out. The evidence about the media’s

treatment of women candidates is very mixed; it is unlikely that the

explanation rests there. It is not that women are at a disadvantage with

campaign donors. It is not that women are running and winning now but

there just aren’t enough open seats. Those cannot tell us why there are not

more women in office.

The problem that stands out is that women do not run for

office. Other scholars have found that women do not have nearly as much

confidence as men that they can win, even when their actual qualifications are

equal. And it is no wonder that women do not have confidence, since

people genuinely believe that it is much harder for women than men to win over

the public. It would actually be quite rational for women to opt out of

running for office if it that really were true! But my study shows that

perception is not accurate.

Women with leadership potential, and the people who might

otherwise encourage them to run for office, need to realize that they are not

at a disadvantage in American politics. Otherwise, the balance of women

in politics may not improve much, even with a level playing field.

Q: What are you working on now?

I am a public opinion researcher at heart, and my work

always tends to focus on issues pertaining to public views politics and

politicians.

For some of my ongoing research, the dimension of primary

interest is still gender. I have a couple of ongoing projects still in

that domain (one pertaining to women as political donors, and another that

looks at how people react to the physical presence of men versus women candidates).

I am also looking into when the public will, and will not,

support going into conflicts with other countries. I started that work

with a co-authored article on whether the conventional wisdom that women are

“doves” and men are “hawks” was correct, and we found that it was decisively

inaccurate for some kinds of wars. My work on that has now moved to other

questions pertaining to war support that have to do with differences between

people that go beyond gender.

Q: Anything else we should know?

Remember to talk to your children about politics as much as

possible! As future voters, and as potential candidates, more girls – and

more boys, for that matter – would benefit from an early immersion in politics

and political issues.

Take your children, or take your nieces and nephews, to the

voting booth with you on Election Day. Talk to kids about candidates, and

the process of running for office. Discuss political news with them, and

encourage political debate around the dinner table. Help them feel comfortable

with the idea that political disagreement is an important part of the political

process.

Besides potentially livening up the dinner table conversation at

home, children who get an early immersion in political issues will tend to end

up being more active and involved citizens in the long run. And that is

good all around.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

Tuesday, November 26, 2013

Monday, November 25, 2013

Q&A with author Nancy Richler

|

| Nancy Richler, photo by Shelia Berlin |

Nancy Richler is the author most recently of the novel The Imposter Bride, which was shortlisted for the 2012 Giller Prize and won the 2013 Canadian Jewish Book Award for Fiction, and also the novels Your Mouth Is Lovely and Throwaway Angels. She lives in Montreal.

Q: You’ve written that part of the

premise for The Imposter Bride came from your own family

history—your grandmother arrived in Montreal and was rejected by the man she

expected to marry. How did you blend that with the book’s fictional elements?

A: Like any fiction, some is from

my own life. My parents were not Holocaust survivors; my grandmother was

rejected at the station. She came over around 1903. Both sides of my family

were here already before the war. The rejection was part of what was in my

mind.

Also, my mother, who was born in

1928, talked about going to the train station in Montreal after the war [to

meet family members who had survived World War II], and the sense of the gap

between them. What they had experienced was something she couldn’t comprehend. [In

addition], there was a stigma attached to them. I was trying to capture a

little of that gap my mother expressed, and how it played out in the community.

Also, a close friend had told me

that her family name had been stolen from someone who had died in a DP camp who

had passage to Canada. Since I’ve written the book, I’ve heard from people with

the same experience. It’s still very hard to get into our two countries.

Q: The issue of names and

identities plays a large role in the book. What do you think people’s names at

birth mean to them?

A: I have such an obsession with

names! It’s in my other book too. I have to discipline myself when I write.

It’s not just personal. We’re so aware

of whose name we carry. With my friend, nobody had survived in that family, and

the name was gone forever. Yet the other name with no living people was reborn.

In the book, that plays out with the

question of what responsibility [Lily] has to that name she stole. A lot of her

quest in the beginning is about that. She makes an effort to connect.

Q: What kind of research did you

need to do to write the book?

A: With this book, I didn’t do any

research. My other book was research, research, research.

I’m 56. For me, we didn’t start

hearing about the Holocaust in my early childhood. My character is 10 years

older. Everyone knew something horrible had happened, but we were getting our

information from observing the adults around us.

Montreal had a very high

proportion of Holocaust survivors. I went to school in a newer immigrant part

of town, and many of my friends’ parents and my teachers were Holocaust

survivors. They didn’t tell us direct things. I wanted to show it from Ruthie’s

perspective.

I did some research about diamond

cutting, and about borders and smuggling, but none of anything else in the book

was researched.

Q: Why did you decide to tell the

story from multiple perspectives, but only Ruthie’s sections are in first

person?

A: This book was torture. I started

it eight years before I finished. I couldn’t get inside Lily’s perspective. I

was stuck for several years.

Then at one point, Ruthie’s voice

came to me, and I decided I’d tell it from the perspective of the daughter; it

was the only one I was qualified to write from.

It’s all from her perspective, so

there are some huge gaps. People have asked, Why isn’t her father angrier? He

didn’t show that to her. There are hints about what happened to Lily, but not

the full story, because it’s written from the perspective of the daughter.

I didn’t feel I could personally

take on the first-person voice [of Lily]; there was a gap of understanding [given her experiences].

Q: Have readers identified with

one character in particular?

A: I’ve had extraordinarily

amazing responses from the children of Holocaust survivors, strong positive

responses. They identify very strongly with Ruthie.

I was in Winnipeg last week, and

it was the first time I had a Holocaust survivor identify with Lily. A lot of

people have been angry that Lily abandoned her daughter, there’s a strong

visceral response. She [the Holocaust survivor] said she could really understand

it. She couldn’t be fully present, and she could understand someone [doing what

Lily did].

Generally, though, people have

identified with Ruthie.

Q: So many novels focus on

dysfunctional families. Your book certainly involves a difficult family situation,

but also has a very close loving family at its heart. How do the two elements

come together?

A: It was a very functional

family. They all pulled together and raised [Ruthie].

That was the family that came to

me. My own family was very functional. I saw a lot of loving families growing

up. By and large, people are trying their best with their kid. I think

sometimes writers feel there’s no story unless there is a problem.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I’m working on trying to start

another novel. I put aside my time every morning, but instead I’m taking

two-hour walks, checking my e-mail, and cleaning the house obsessively. I’m in

an avoidance state.

This book came out two years ago,

but in Canada it really gathered steam last year. I’ve been traveling with it; it’s evoked a strong response.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

Sunday, November 24, 2013

Saturday, November 23, 2013

Friday, November 22, 2013

Q&A with author Lavanya Sankaran

Lavanya Sankaran is the author of the novel The Hope Factory and the short story collection The Red Carpet. She lives in Bangalore, India.

Q: How did you come up with your two main characters, Anand

and Kamala?

A: Indian cities are full of exciting opportunity for those

who have dreams – but the path to realising those dreams is not easy; there are

obstacles and complications and risks.

Kamala’s life is inspired by countless women like her, who

battle extreme odds and adversity and keep their dream of educating their

children to a better future.

The crux of Anand’s story – a good, capable man, fighting to

keep his head above water – clarified for me late one night after, of all

things, a television program. I was watching a National Geographic special on

American pioneers and what it took for them to survive and succeed in such a

hostile environment – and that’s when it clicked.

I realized I was seeing something similar all about me: for

years, I had been watching people struggling to build world-class businesses in

an environment that didn’t support them in any of the crucial ways.

When a government is corrupt and inefficient and does not

deliver on its basic promises, it leaves its citizens in a fearsome, dangerous

and lonely world – and those who succeed, like those rugged pioneers, are the

exceptional individuals, hardy, uncompromising, uncomplaining.

Q: What role would you say the city of Bangalore plays in

The Hope Factory?

A: Bangalore has been the perfect muse for this particular

story. It is the classic small-city-grown-big – in huge part driven by the

dreams of all the immigrants who have flocked to it. It is the perfect

microcosm of life in urban India and works almost as a character in the story.

Q: You blend humor with some serious issues. How do you

balance the two?

A: Humour is vital to how I process my understanding of the

world. In my personal life, I have to say, my sense of humour is akin to that

of a drunken undergraduate – but employing wit and humour in storytelling,

especially in a story that carries more serious dramatic themes, is a delicate

operation and one that needs to be carefully managed.

Q: You've also written a short story collection. Do you

prefer one type of writing to the other?

A: They were both interesting and fulfilling and challenging

– and amazingly different from each other in terms of process and method.

Going forward, I find myself writing a couple of short stories, and

working on the fabric of a new novel.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: I love writing; I love the process. Sure, it’s not easy –

but when it goes well, nothing feels better.

And when I’m done writing and rewriting something, when the

editing has been (finally) laid to bed – I’m amazed at how quickly the story

drifts away from my mind and I’m turning my attention to something new.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

Thursday, November 21, 2013

Q&A with writer Heather Arndt Anderson

Heather Arndt Anderson is the author of the new book Breakfast: A History. A food writer, she has a blog, Voodoo and Sauce, and has contributed to a variety of publications, including the Food Cultures of the World Encyclopedia. She lives in Portland, Oregon.

Q: How did you end up writing a book about breakfast?

A: The answer to this question is not very romantic,

unfortunately! I had heard that Rowman & Littlefield was doing a series on

the meals, and I prepared a proposal and sample chapter. I guess ten years as

an environmental consultant taught me how to respond to an RFP, because I got

the job.

Q: What did you learn that surprised you the most?

A: Honestly, I learned so many things writing this book. I

loved learning about the Kellogg brothers and the fraternal divide over sugar;

that wacky, faddish diets are nothing new.

I think one of the big surprises was that a free breakfast

program had been in effect for nearly a century in English schools before

Americans instituted a similar program, and that the FBI found the Black Panther

Party's Free Breakfast Program for Schoolchildren to be more threatening than

any of their direct action tactics.

Q: How did breakfast cereals become so popular?

A: I think that wartime meat and egg rationing played a

fairly significant role in getting cereal into so many (non-Adventist)

households in the first place, but an even bigger factor was that many mothers

had begun to take employment outside the home. Women were smitten with a food

they could simply pour into a bowl.

Another aspect of the changing American household is that

postwar, children were becoming more independent because parenting guides (and

cereal advertisements, naturally) were extolling the psychological benefits of

kids doing things for themselves, including fixing their own breakfast.

Of course, the implication was that it was good for

children, but as a mother I can attest that it is also good for busy

moms!

Q: What is your favorite breakfast?

A: I waffle (ha) between French toast with sausage and a

good breakfast burrito if I have my druthers. If I'm in a rush, which is most

weekdays, I am happy with good, strong coffee and wheat toast with butter and

homemade marmalade.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I'm currently about halfway through a book on the

culinary history of my hometown, Portland, Oregon. It will be out in about a

year from now.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: Yes! I will be presenting a talk on breakfast as metaphor

in film and television in February, at Omnivore Books in San Francisco, and I

do regular speaking gigs on bits of esoteric history at the Jack

London Bar in downtown Portland. In the words of the insatiable Mae West, come

up and see me sometime!

--Interview with Deborah Kalb

Q&A with author Judy Pomeranz

Judy Pomeranz is the author of the new novel Love Without Asterisks. She is a freelance writer who has lectured on art history and taught fiction-writing classes. She lives in Chicago.

Q: How did you decide on the

title Love Without Asterisks?

A: The work was originally

published in serialized form, in fifteen monthly segments in élan Magazine,

under the title “On the Far Edge of Love: New York Stories.”

The story evolved as I was

writing it, month by month, and at one point my character Frank alluded to his

relationship with his late wife as having been “…perfect. No qualifiers, no footnotes, no goddamn

asterisks.” I entitled that segment

“Love Without Asterisks.”

When I was later re-working

the manuscript into a single long-form work, I realized this kind of love was

fundamentally what nearly all the characters were, in one way or another,

seeking, and thus it seemed an apt title for the book.

Q: Why did you decide to tell

your characters’ stories from multiple points of view?

Much of the fun of writing

the book, for me, was diving and delving into the heads and motivations of each

of my very different characters.

Seeing the world through each

of their own sets of eyes seemed like the most honest and organic way to

do this. In the process, I naturally filtered what they filtered, adopted their

unique perspectives, and perceived reality as each of them did, rather than as

some objective arbiter of the way things are.

So, honestly, it was for my own pleasure.

Q: Among your various

characters, did you have a favorite?

A: I actually like each of

them, with the possible exception of Mike, for their own humanity, and I sympathized

with each of them as they negotiated their way through their own lives.

I am particularly drawn to

Isabelle, who broadened her worldview – though not entirely voluntarily – at a

rather advanced age. I am also drawn to

Larissa, for her poignant combination of swagger and vulnerability.

Q: Could you explain more about your writing process as you worked on the book?

A: As I mentioned, I wrote

this month-by-month as a serial, and I did not know how it would end. I

relatively early developed a sense of the overall trajectory of each

character’s life, but did not know what their outcomes in the story would

be.

This made the writing fun for

me, as I was telling myself the story as I went along, but also a little scary,

as I wasn’t sure all the pieces would ultimately come together!

Q: What are you working on

now?

In terms of new work, I have

returned to the short story form for the moment. In the course of working on my

M.A. at Johns Hopkins, I learned to love crafting short stories, in which each

word must be carefully selected and add to the overall goal. And of course I

enjoy the more immediate gratification of completing a short story!

At the same time, I am

working on getting my first two serialized novellas (both of which are set in the

Manhattan art world) into book form. I

look forward to eventually having the three Manhattan books form sort of a

trio, though not a trilogy, as each features entirely different characters and

is set in a different time period.

Q: Anything else we should

know?

A: Though I have published a

fair number of short stories and hundreds of art reviews and articles over a

period of nearly two decades, having my first novel published and listening to

people talk about my characters and their idiosyncratic issues is an amazing

thrill.

Wednesday, November 20, 2013

Q&A with author Harriet Scott Chessman

Harriet Scott Chessman is the author of the new novel The Beauty of Ordinary Things. Her other books include Someone Not Really Her Mother, Lydia Cassatt Reading the Morning Paper, and Ohio Angels. She lives in the San Francisco Bay area.

Q: Why did you decide to make one of your main characters a

Vietnam veteran?

A: Benny Finn came to me from the start as someone who had

suffered -- someone who had great sensitivity, and who couldn't shut out his

suffering, or that of people around him. I also knew, from the first, that

he was the oldest child in a large Irish Catholic family, in a suburb of

Boston, in the early 1970s.

Having been a college student myself in 1968-72, I will

never forget the centrality of the Vietnam War in all our lives then. The draft

was an ever-present reality, quite frightening, as were the images and news

stories coming out of Vietnam each day.

Pretty soon in my writing about Benny, I realized that this

character's sense of suffering and despair could arise in part out of his

experience as a soldier in that incredibly difficult War.

Q: How did you choose the title, The Beauty of Ordinary

Things?

A: This may sound ridiculous, but I first discovered this

phrase in a Chinese restaurant's fortune cookie: "You appreciate the

beauty of ordinary things." (!!) I loved that! and held onto

that little white piece of paper, and the idea of ordinary things as shining

with an inherent beauty, for a long time.

The first title I chose, seven years ago, was actually Benny

Finn Writes to God, yet once I started adding in additional voices (at first,

my character Isabel's, and then Sister Clare's), I wasn't sure this title fit

100%.

The letter Benny writes to Sister Clare, about how ordinary

things help him stay in the world, inspired me to choose The Beauty of Ordinary

Things as my new title.

I felt confirmed in this choice when I came upon the concept

of "Ordinary Time," in the Catholic liturgical calendar. Benny and

Sister Clare tell their stories over the course of the summer of 1974,

primarily in Ordinary Time (from the Monday after Pentecost to the Saturday

before the First Sunday of Advent).

I also discovered that Thomas Merton has written powerfully

about the importance of remaining open to the sacred within each moment and

object and person. In No Man Is An Island, he writes about "the value and

the beauty in ordinary things." I have yet to study Merton's work, and

hope to do this soon!

In a larger sense, I wanted to write a book that honored the

ordinary and the modest. Like Benny, I wanted to do what I could to tell

the truth, without bells or whistles.

I felt that it was only in that effort that I would be able

to come anywhere near the hem of the garment of the sacred. The sacred is IN

the ordinary -- this is something I deeply believe. Yet I don't think it can be

written about easily or directly -- at least, I couldn't figure out how to do

this.

By focusing on my characters and their choices, the daily

nature of their lives, I hoped to gesture toward something sacred, something

deeper, threading through.

Q: What do you see as the role of Sister Clare's convent,

and what impact does it have on the various characters?

A: I think this story depends on Our Lady of the Meadow, the

Benedictine Abbey I imagine here. I didn't realize this in earlier versions of

the novel; it was something I gradually came to understand.

For Benny Finn, as for Isabel Howell (the young woman with

whom Benny falls in love -- his younger brother Liam's girlfriend), the Abbey

is a place of stability and growth. As Benedictines, the members of this

Community vow stability (literally, to remain in place), conversatio morum (to

change one's ways, and also to be constantly open to change), and obedience.

In the chaotic, brutal experience of war, and even in the

difficulty and chaos of ordinary life, Benny especially is missing all of these

elements. He is missing the sense of this world -- our world -- as filled with

significance, love, and meaning. His family is loving, of course, yet I felt it

to be important that he find a new place where he could at last, in a sense,

lie down and weep, just totally let it all go, before he could start to rise up

again and get to work at the business of living, within a new framework.

Sister Clare offers him a model of a life focused on

something greater than oneself -- something that requires devotion, labor, and

grace. Accepting a form (the hours of the office, the Benedictine Rule) helps

her rise out of the confines of her own self, as she strives to live with

greater freedom.

It's a paradox, I know, but I do believe this can happen --

to accept a kind of architecture to one's life, a sense of parameters, and to

dedicate yourself to this form of life, can actually free you and open you to

growth. I feel that, in my own life, writing has been like an Abbey.

Q: What kind of research did you do to write this novel?

A: Our Lady of the Meadow, in my novel, is inspired by a

wonderful Community I have known for thirty-five years: The Abbey of Regina

Laudis, in Bethelehem, Connecticut. A beloved friend, Mother Lucia Kuppens,

O.S.B., entered this Abbey in 1979, after gaining her PhD in English with me at

Yale University, and I have always honored and been amazed by her choice.

In a sense, I think I wrote this novel toward her, trying to

understand at least some fraction of her life. She is one of the kindest,

wisest, and most compassionate people I have ever known, and also one of the

most modest, private, and contemplative. Through her I came to know many of the

vibrant nuns in this Abbey.

Like my character Isabel, I have often picked apples or

gooseberries, beans or potatoes; I've had the chance to walk through the

pastures to greet the cows; I've listened to the Gregorian chant and heard the

prayers and homilies; I've celebrated magnificent occasions and anniversaries; I've

tasted delicious Abbey meals.

Still, I have been woefully aware of my ignorance. I

grew up Baptist, not Catholic, and I did have to do quite a bit of research

into both Catholicism and Benedictine life.

I also read books and essays about the Vietnam War.

One of the books that has meant the most to me is Tim O'Brien's TheThings They Carried.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I am actually writing the libretto for an opera being

composed by my friend Jonathan Berger, a magnificent composer who teaches at

Stanford University.

This opera, in Jonathan's vision, is about Hugh Thompson,

the helicopter pilot who intervened in the massacre at My Lai on the morning of

March 16, 1968. It has been fascinating and thrilling to have the chance to

work with Jonathan in this quite different form.

Hugh Thompson was an extraordinary person -- heroic in the

way he courageously and passionately followed his heart and conscience that

day, not the orders of his superiors -- and it's a great joy to be able to

contribute to a work in his honor.

I also have short stories in the works, and I may go back to

wrestling with a novel, located in 19th century New Orleans.

Q: Anything else we should know?

A: I feel incredibly lucky to have the chance to write, and

even luckier to have found a publisher -- Mark Cunningham of Atelier26 Books --

willing and eager to accept a novel this compact and literary, within such a

daunting publishing climate.

Mark is a publisher with great vision and humanity. I would

love to see the rest of the book world follow his lead, as he focuses on

genuinely literary work, in beautiful editions (real paper and gorgeous

design!). He is devoted to independent bookstores, and has created an inspiring

website honoring literature and these special indies, so important to our

cultural life.

I hope your readers will enjoy looking into this beautiful website of Atelier26 Books. For more information about my writing, readers are also

welcome to look into my own website. I am also on Facebook, and welcome fellow readers and

writers.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb. This interview also appears on www.hauntinglegacy.com.

Q&A with author Eve LaPlante

Eve LaPlante is the author most recently of Marmee & Louisa, a biography of Louisa May Alcott and her mother. She also edited My Heart Is Boundless, focusing on the writings of Abigail May Alcott. Her previous books include American Jezebel and Salem Witch Judge. She lives in New England.

Q: How similar is the relationship between the real Louisa

and Abigail to the fictional relationship between Jo and Marmee in Little Women?

A: The fictional relationship portrayed in Little Women is a

nugget of the actual relationship between mother and daughter, which was more

difficult and complex.

Alcott took a slice of the relationship she had with her

smart, loving, encouraging mother and gave us that in Little Women. What she

left out was a lot of pain: the homelessness the Alcotts endured for thirty

years, the marital strife her mother experienced, and their poverty. You might

say she cleaned it up when she wrote Little Women.

In fact, the stable, happy home in Little Women seems more

like the home Abigail grew up in, as the youngest of four girls, a comfortable

house in early nineteenth-century Boston, still a pretty country town.

Q: What surprised you the most as you researched this book?

A: I was most surprised to learn how important the real

Marmee really was to the story of Louisa May Alcott. Because everyone thought

Abigail’s papers were all burned after she died, everyone had pretty much

ignored her except insofar as she was a long-suffering housewife and mother.

I was amazed to learn that Abigail was Louisa’s mentor and

muse – the person who gave Louisa her first journal and encouraged her to

write, not only in childhood but for decades. Abigail was also Louisa’s first

reader, and the inspiration for many of Louisa’s stories. Louisa read over her

mother’s lengthy personal journals, at her mother’s insistence, looking for

ideas to write about. That was a big surprise.

Q: What does the Alcott family’s story say about attitudes

toward women in the 19th century, and what is similar to the choices women face

in more modern times?

A: Abigail did not fit into her society. The ideal woman

then, and throughout most of American history, was a docile, nonintellectual

homebody.

Abigail was more like women today. She wanted girls to be

equal to boys, and women to have the same opportunities and responsibilities as

men.

Her unusual social and political views included a belief

that women should vote and participate in public life. She opposed slavery in

the 1830s, when proper Boston society considered abolition insane. As one of

American’s first social workers, she sought ways to alleviate urban poverty,

and as a mother she gave her daughters all the encouragement to do whatever

they felt called to do – have a career, marry, travel, and seek their fortunes.

These opportunities had not been available to her.

But she had enjoyed a happy girlhood in a comfortable house

filled with books and sisters, with a devoted older brother who encouraged her

desire to be educated and equal to him.

Q: You have family connections to the Alcotts and Mays, and

also to other figures you’ve written about. How do you think that biographical

connection affects your writing, or your choice of subjects?

A: My family relationship to my subjects gives me a sense of

kinship with them, but it doesn’t seem to change the research and writing.

There is no question that as a child I had trouble

identifying with my famous ancestors, and of course a biographer must be able

to identify with her subjects. As an adult who has had the privilege of coming

to know these people through their own words, I view them as three-dimensional

figures with gifts and flaws who deserve my respect and sympathy.

The family tree did give me the subjects of three books: Salem

Witch Judge, about the repentant 1692 jurist who became America’s first

abolitionist and feminist; American Jezebel, about Anne Hutchinson; and Marmee

& Louisa.

If my Aunt Charlotte, the family genealogist, hadn’t told me

stories about my family’s past when I was small, I would never have known to

explore the lives and times of these fascinating people. Their stories are so

great, in fact, I wish I had more ancestors like them still left to explore!

With Marmee & Louisa, I had something special that

didn’t exist for the two previous ancestor biographies – family papers in an

attic trunk. That was a biographer’s dream.

In trunks that came from my late great-aunt, Charlotte May

Wilson, I found a book inscribed by Louisa May Alcott to her 10-year-old cousin

George “from his cousin Louie.” That became the opening scene of Marmee &

Louisa. I found an 1823 family Bible, memoirs and letters of Louisa’s first

cousin my great great grandmother Charlotte May, and Louisa’s uncle, Samuel

Joseph May, Abigail’s brother and lifelong ally.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: Lacking more ancestors to write about, I’m experimenting

with fiction, an exciting new challenge. I hope to be able to tell you more

about that soon.

--Interview with Deborah Kalb